Finding a new job after hanging up the tennis racquet

- Published

Not all tennis players retire having made a fortune in the game

When Li Na announced her retirement from tennis last September, the two-time Grand Slam champion had banked as much as $24m (£16m) in the 12 months preceding her decision.

Former British Davis Cup player Jamie Baker, who'd once been ranked number two in the British game, made his decision to quit in June 2013.

However, his career earnings over nine years of competition totalled a more modest £360,000.

Both players had battled significant injury and fitness problems during their time on tour, but their future prospects were worlds apart.

Corporate division

Li Na, 32, one of the most recognised, inspirational figures - not merely in China but throughout Asia and beyond - commanded huge off-court commercial value.

Li Na retired at the top of the tennis tree and worth millions

In contrast, Mr Baker, 26, had achieved a career high ranking of 186 in 2012, but had nothing like the sponsorships and endorsements enjoyed by the Chinese player to show for his dedication.

So, looking for a new job took him completely out of his comfort zone, having previously given little thought to anything else except succeeding at tennis.

"I knew there would be a life [outside tennis]. But I definitely didn't know what that was going to be," he says.

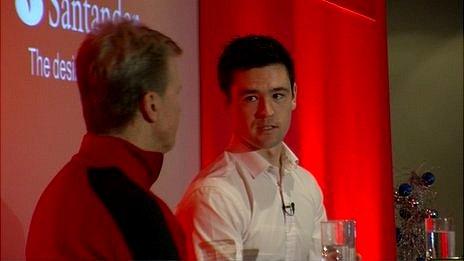

We are sitting in the same London head office where he was interviewed last autumn for a role - one that he now holds - within the UK corporate division of bank Santander.

'Assess the options'

Unlike many players confronted by such a stark change in circumstances, Mr Baker had actually made moves in the months before he stopped playing.

"I knew who I was going to speak to, and how I was going to get in front of as many people as possible, to assess the options," he says of those job hunting days.

Jamie Baker has been telling bankers about how sport can influence business

And, importantly, he sought advice from the British game's governing body - the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) - where he was introduced to its senior performance lifestyle advisor, Rachel Newnham.

She says: "Most tennis players have few qualifications. They left school early on. Education is looked on as if it's 'tennis or nothing'.

"They think they're going to stay in tennis. They think that coaching is the next thing they're going to move on to."

Plan B

For Mr Baker, however, coaching was never the goal. With a brother already working as a trader in the City, he had an inkling of another, off court, world.

But it was Ms Newnham's contact at a recruitment agency that properly set him on his way into banking.

"Part of the reason I wanted to stop [playing] was to give something else a go," he says. "It was just a question of when."

Rachel Newnham says lower ranked players are more aware of the challenges

He said he was made aware of the many different jobs in finance, not just City trading, and that such knowledge helped enable him to "give this a shot and get into the business world".

Mr Baker, now 28, has become a role model for Ms Newnham in her drive to make other UK players appreciate what is possible outside of the sport that has consumed them all their lives.

Making such a change involves a change in attitude and culture among players, says Ms Newnham.

She continues: "There is no shame in having a plan B - the smart ones have one. Usually it's the lower ranked players who are aware that they are going to have to do something else after tennis."

'Commitment and drive'

Ms Newnham says although players' CVs may be short of formal qualifications such as GCSEs, the skills they pick up as tennis competitors are transferable and hugely in demand in a lot of jobs.

"Motivation, leadership skills, teamwork, having the commitment, the drive, and focus are hugely thought of by employers these days," she says, referring to these attributes as "life skills that you can't teach".

These words offer encouragement to Tara Moore, 22, who's currently ranked number six in Britain. Her funding was among that cut under LTA reforms announced last December.

Tara Moore is already looking ahead to a working life off the competitive tennis court

She's still keen to make her way in the sport she's played since she was six years old, but understands that her plans may have to change unless her fortunes improve on court.

"I'm finding ways to continue playing tennis but if you're not in the [world] top 100 or 200, you're not earning money. We're barely breaking even," she says.

"If I was to stop today then I would have nothing. I would have to start from zero. And that's incredibly tough, incredibly scary.

"But Rachel shows us that there other things besides tennis, there are so many other things we can do and skills we can use from tennis."

Next move

Ms Moore's house-mate in London is another who appreciates Newnham's expertise.

Oliver Golding, the 2011 US Open Boys' Champion, announced his retirement just before Christmas - at the age of just 21 - and has consulted her on what he might do next.

Currently he's working at his mother's tennis coaching company while working out his next move.

Oliver Golding is looking for a new future after retiring at the age of 21

Around 80% of British players choose to stay in the game either coaching or working in administration.

Martin Lee is among them. Now 37, he runs his own coaching business in Buckinghamshire with another former player Paul Delgado.

'Selfish'

Mr Lee, who reached a career best world ranking of 94, always knew he wanted to work in tennis, following his father who was a coach for 40 years.

Initially after retiring he tried his hand at sports management, but missed the court environment.

His company, Living Tennis, offers tuition from community to elite levels, including coaching a thousand children each week at its eight venues.

Living Tennis provides coaching for players of all ages and abilities

Three years after their launch, turnover has increased to £500,000. Their office is now at Bisham Abbey National Sports Centre, where they won the contract to run the tennis facility.

Mr Lee admits it's been a daunting venture. He says he's permanently tired, regularly working 12 hours per day, seven days a week.

"When you're a tennis player, you only think of one person and that's yourself," he says. "You have to be selfish because it's your career and it's your job.

"Now it's totally the opposite. The last person we think about is ourselves. We've got to get enough money in to pay everyone and we've got to make sure everybody gets the most out of their time."

The same commitment which qualified him to play in Grand Slam tournaments during his ten years on tour now earn him a living in a very different way.

'Big difference'

Mr Lee and Mr Baker find it hard to replace the camaraderie and thrill of competition in their new roles.

Both make time to play the game when they can and enjoy the familiar, instant feedback of winning or losing.

But for Mr Baker, who's working as a commentator at the Australian Open, there is a strong connection between the past and the present which bodes well for the future.

"I feel like my tennis life has prepared me for what's happening now," he says.

"I hope that in 10 or 15 years I will feel I am making a big difference, and I'm really glad that I had the opportunity to go through that journey."