Unmasking China: Winning in the East

- Published

Western business leaders must embrace the country's culture, says leadership expert Steve Tappin

If you listed the factors that can help drive a firm's success in China, being led by a foreigner is not one of them.

Yet French born Raphael le Masne de Chermont has managed to beat the odds. In 2002, he joined glamorous Chinese lifestyle brand Shanghai Tang as executive chairman.

And in just over a decade, he has managed to switch the firm from a single Hong Kong store aimed at Western tourists who wanted a Chinese souvenir of their travels, into a luxury brand attractive to Asian and Chinese shoppers.

This is no mean feat. When he joined the firm there was no such thing as a high-end Chinese brand. Locals shopping for designer labels would look to overseas names such as Hermes or Burberry.

Shanghai Tang pairs western and Chinese designers together to work on products

The secret to Shanghai Tang's successful turnaround was balancing the "knowhow of the West" with the "culture of the East", says Mr le Masne de Chermont.

In practice, this meant pairing up Chinese and Western designers to work together on the firm's products, which range from clothing to home furnishings.

"The Chinese will bring his culture and his feeling and his sensibility and, the Western designer will bring the style, the fabrics, the best practice of international fashion," he says.

Today, the firm continues to run its business in the same way, with half of its designers Chinese and the other half Italian and French.

His simple advice to Western leaders looking to emulate Shanghai Tang's success in China is "modesty".

"It's true for every business man going to another culture. You have to understand the new culture and you have to adapt to it."

Firms want to access China's fast rate of growth

It's sage advice. China has become a priority for firms seeking growth. As the world's most populous country, its burgeoning middle class offers massive opportunities. But it's easy to underestimate just how different doing business there is compared to overseas.

Leadership expert Steve Tappin, who works with both Chinese and Western chief executives, says many bosses assume that doing well at home means they will succeed in the East.

"Too often Western business leaders believe that their way is the only way and that one size fits all," he says.

Home Depot decided to close its large stores in China

There have been plenty of casualties, from European retailer Metro, which pulled out of the Chinese consumer-electronics business after two years of testing, to US home improvement chain Home Depot, which decided to close all its large stores in China.

Liu Chuanzhi, founder and chairman of Chinese computing giant Lenovo, says often the problem stems from a purely theoretical understanding of how businesses operate.

"Most of their stock of knowledge or experiences on how to run a company comes from their schools, from their universities and is based on their experiences over the years. But in China sometimes it's a different situation."

A personal friendship is still often a prerequisite for doing business in China

For the head of a western firm visiting China from the back of a chauffeur-driven car and staying in top-of-the-range hotels, it can also be hard to get a genuine grasp of daily life. Even when a westerner lives in China, their experience is often different.

They live in a good residential area with lots of other ex-pats, send their children to international school and have limited interaction with the "real" China, says Joe Baolin Zhou, chief executive of Bond Education Group, the largest private education service company in southern China.

This means the complexities of life in China can take a long time to grasp fully.

For Western firms to fill in the gaps in their knowledge they need to recruit local business leaders, he says, or Chinese people who have returned from overseas, and put them into senior positions to provide better insight into the Chinese market.

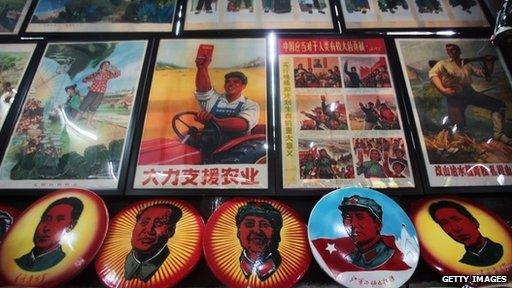

But the biggest lesson of all is that firms need to be patient. An overhang from past foreign invasions and the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, when families and friends were encouraged to report on one another in a bid to enforce Communism, has created a natural wariness of strangers.

The Cultural Revolution helped create a natural wariness of strangers in China

And when China first started to encourage development of a market economy there were no proper networks or written contracts, so doing business with a known network was initially the only way to ensure that they wouldn't be taken advantage of.

A personal friendship is still often a prerequisite for doing business in China, and that takes time to establish.

Jeff Immelt, chief executive of US giant General Electric (GE), estimates he's been to China about 75 times over the past 25 years.

"The way that our position has [been] built in China has been one brick at a time, one relationship. You know, hundreds of meetings. We've earned the right, I think, to be a good Chinese company in GE only because we put in decades worth of work," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.