Why no le Pen or Farage at Davos?

- Published

- comments

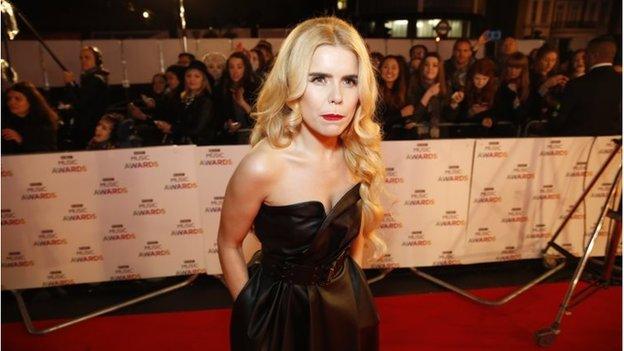

Paloma Faith opened her set at Google's Davos jamboree by shouting - with no apparent sense of irony, as the vintage Bollinger flowed - "let's spread the 1%".

What she meant, presumably, was "let's find a way to redistribute some of the almost-50% of the world's wealth controlled by the richest 1%" - who undoubtedly include Paloma Faith.

The World Economic Forum at Davis isn't thronged by the best-heeled 1% of course. It's in effect the annual general meeting of the top 0.01% - the super elite of the wealthy and the powerful.

It is where billionaires and business leaders buy access to world leaders and top central bankers. It is where, over coffee and cake in the day, and champagne and canapés at night, what would once have been called the ruling class get together to share their cares.

And it wasn't just Paloma Faith who apparently thinks her financial rewards aren't fair. This year I was challenged to find a plutocrat who wasn't fretting about the widening gap between rich and poor - an inequality gap in the world's biggest economy, the US, which is now back to where it was in the 1920s.

Part of the super-wealthy's angst may be survival instinct. Because all over the world millions of people left behind by globalisation, whose living standards have been squeezed, have been voting for populist, and often nationalist, parties - which promote policies frequently inimical to the material interests of the rich.

Davos Man

And the popularity of the likes of Syriza In Greece and France's Front National is - to state the blindingly obvious - inimical to the interests of the mainstream parties.

Davos Man and Davos Woman have a horrified fascination with the anti-austerity new left of Spain and Greece, whose Syriza may triumph in Sunday's election.

And they appear bewildered and anxious about the rise and rise of anti-immigration, eurosceptic UKIP in Britain and the Front National in France.

For the Davos set, the rise and rise of the Front National's Marine le Pen - who wants a return to protectionism and also nationalisation of France's most important companies - is especially troubling.

Senior French politicians concede she is formidable. Having interviewed her recently, it is hard to disagree.

And they have no very compelling strategy to check her advance, other than a hope that there will still be enough liberals and moderates in France by the time of the 2017 presidential election to vote in an anyone-but-Marine, centre-ground candidate.

Populist parties

The hope at Davos is that as and when leaders of the populist parties scent real power, when the realities of governing dawn on them, they will drop their more extreme ideas and be co-opted into the mainstream. And the softening of Syriza's previous hostility to remaining in the euro may support that optimism.

But a le Pen and a Nigel Farage of UKIP more-or-less define themselves as the antithesis of Davos person. So the idea that the populists could ever want to join the Davos gang seems naive.

It is striking and important that at a time when populist parties pose an arguably existential threat to European Union and eurozone, there is not a single representative of any them at the summit of the Swiss mountain (or at least not that I could spot).

But if Farage, le Pen and Tsipras aren't here, Davos risks being seen as too removed from the big political and economic debates of our time, or at least those who excite a growing number of citizens.

Today Davos, as it did after the 2008 banking debacle, feels a club of the existentially challenged, ancien regime, perhaps.

Davos and the World Economic Forum will be around for many years yet. But it's habitués risk defenestration, loss of their licence to govern, if they're unable to respond effectively to the new demagogues' charge that they are not saving the world, as they claim, but only their own precious privileges.