Why aren't markets panicking about Greece?

- Published

- comments

The Greek people don't seem desperately grateful for the 240bn euros in bailouts they've had from the eurozone and IMF - and here is one way of seeing why.

The country's economic crisis was caused in large part because its government had taken on excessive debts.

So at the time the crisis began in earnest, at the end of 2009, its debts as a share of GDP were 127% of GDP or national income - and rose the following year to 146% of GDP.

As a condition of the official rescues, significant public spending cuts and austerity were imposed on Greece. And that had quite an impact on economic activity.

The country was already in recession following the 2008 financial crisis. But since 2010, and thanks in large part to austerity imposed by Brussels, GDP has shrunk a further 19%.

GDP per head, perhaps a better measure of the hardship imposed on Greeks, has fallen 22% since the onset of the 2008 debacle.

So austerity has certainly hurt. But has it worked to get Greece's debts down?

To the contrary, Greek debt as a share of GDP has soared to 176% of GDP, as of the end of September 2014.

Now it has fallen a bit in absolute terms. Greek public sector debt was 265bn euros in 2008, 330bn euros in 2010 and was 316bn in September of last year.

But it is debt as a share of GDP or national income which determines affordability. And on that important measure, Greece's debt problem is worse today than it was when it was rescued.

To state the obvious, it is the collapse in the economy which has done the damage. And although Greece started to grow again last year, at the current annual growth rate of 1.6% (which may not be sustained) it would take longer than a generation to reduce national debt to a manageable level.

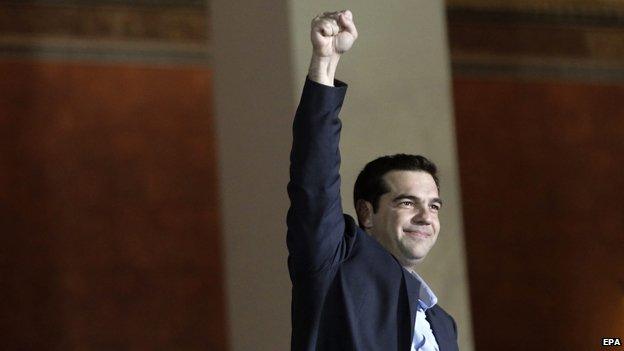

Alexis Tsipras, leader of the triumphant Syriza party

Little wonder therefore that a party - Syriza - campaigning to end austerity and write off debts, has enjoyed an overwhelming victory in the general election.

That it appears to be two seats short of a clear majority in the Athens parliament should not disguise the clear message sent by Greek people to Brussels.

Or perhaps it would be more apt to talk of the message being sent to Berlin - since it is Germany which has been the big eurozone country most wedded to the economic orthodoxy that there's no gain without austerity pain.

As for investors. there are two reasons why Syriza's victory is significant.

First, and as I've mentioned, its leader Alexis Tsipras has a clear mandate to negotiate an easing of austerity imposed by Brussels and the IMF, and a write-off of at least some of the country's massive public sector debts.

At the moment, he and his colleagues are stressing that they want to negotiate and are sending out emollient signals. But the Germans are saying that the deal done with Greece in the rescue is the deal that holds.

So compromise may prove impossible - Greece rudely ripped from or bolting from the eurozone is not an impossibility,

The second reason the victory is significant is that younger anti-austerity parties are on the march all over Europe, and are doing especially well in France and Spain.

If Syriza were to win its negotiations with the rest of the eurozone these other anti-austerity parties would look more credible to voters. The victory of protectionist, nationalising Marine le Pen in France's presidential election would be an interesting test of markets' sangfroid (ahem).

And if Syriza were to lose in talks with Brussels and Berlin, and the final rupture of Greece from the euro were to take place, investors might well pull their savings from any eurozone country where nationalists are in the ascendant.

So why aren't investors in a state of frenzied panic? Why have the euro and stock markets bounced a bit this morning? One slightly implausible explanation is that investors believe the eurozone would actually be stronger without Greece, so long as no other big country followed it out the door.

More likely is that they believe reason will prevail, and Berlin will sanction a write-off of Greece's excessive debts.

Here is the important point: outside of Germany it is almost impossible to find an economist or central banker who believed that the previous reconstruction of Greek debt was ever going to work.

So just maybe, after Greeks have made a colossal and some would say pointless economic sacrifice, Germany will allow a rescue that permits the country a fighting chance of crawling out from beneath its colossal debts.