Waste not, want not - making money from rubbish

- Published

Tom Szaky talks 19 to the dozen. It's as if he doesn't want to waste a single minute of the hour-long interview I have with him.

But then waste is a subject dear to his heart. He is the founder and chief executive of social enterprise TerraCycle, a company whose aim is eliminating waste.

"It's a lofty ideal I know," he says, but so far so good.

In 13 years, US-based TerraCycle has gone from the classic start-up run out of a basement to operating in 21 countries. Last year it had revenue worth $20m (£13m) and 115 employees.

The company's business model is to find waste and turn it into something useful, for a profit. It collects things that are generally considered difficult to recycle - such as cigarette stubs, coffee capsules, or biscuit wrappers - and finds a way to reuse them.

That is done mainly through processing them down into a material and selling them to a manufacturer, and to a lesser extent by turning them into products such as bags, benches or dustbins.

It relies on contracts with businesses - such as McVities, Johnson & Johnson, and Kenco - that pay TerraCycle to take away their waste, as well as individual consumers collecting and sending it in, in return for donations to a charity of their choice.

Hungarian experience

With messy hair, jeans and sweatshirt, Tom, 33, is typical of the new breed of young entrepreneur that shuns formality.

Yet he goes one stage further - he's worn the same pair of jeans every day for the past year (except for the weekend when they're washed) as part of his attempt to consume less.

Born in communist Hungary, Tom fled the country with his parents at the age of four, ending up in Canada, via Holland, aged 10. He says his whole business model is borne out of his experience of the two different economic systems.

The TerraCycle office in the US uses recycled bottles as wall dividers

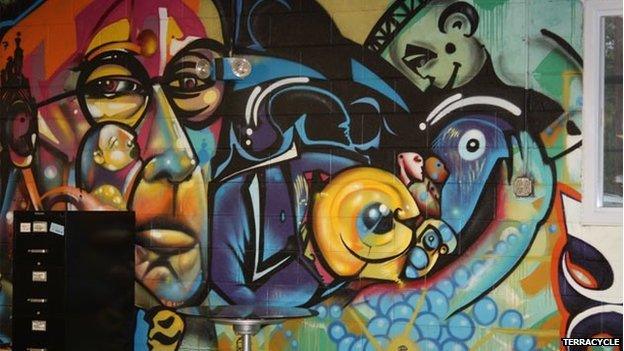

Most of the offices have some form of graffiti on the premises

TerraCycle offices are usually based in less wealthy parts of town

"In Hungary back then, you needed a licence for a TV set," he explains.

You couldn't just go and buy one. Instead, after applying for a licence maybe a year later you'd get a black and white TV, and you'd get the one state channel.

Tom says: "Only a few years later we end up in Canada where every Friday my dad and I would drive round and see mountains of TVs thrown out of every apartment buildings.

"We'd pick a few up just for fun - because we thought 'who would throw out a TV?' and they all worked and they were colour!"

This, he adds, got him to thinking about the concept of waste. At the same time, he was impressed and inspired by the entrepreneurs he met in Canada (parents of friends of his), and decided he wanted to run a business.

Profit driven

TerraCycle was set up in 2002 after Tom, then 19, dropped out of Princeton University in New Jersey to develop an idea he had - much to the chagrin of his parents, who strongly believed in the importance of his education.

"Yeah, [it was] one of those moments where the child tells the parents this is my life, and I shall do as I wish. A breakthrough moment in that sense," he acknowledges.

The first product that TerraCycle made was an organic fertiliser created from "worm poop". Within five years, the firm had sales of around $3m to $4m, but was making a loss. It was then that Tom realised that the approach was wrong.

Companies with TerraCycle contracts

"We were trying to come up with a product and then find the best type of garbage to make it.

"Five years into the business we totally pivoted everything," he says. "Instead of starting the question with the product, we said let's start with the garbage… we need to solve crisp bags, cigarette butts and so on."

Without that realisation, he reckons TerraCycle could never have been profitable. And he's a firm believer in profit.

"Many young entrepreneurs think you can either do good for the world and earn nothing, or you can do something negative and earns loads of money.

"I don't choose either - I want to make a lot of money by doing good.

"People are also motivated by personal return. If I sell this company I'll make millions, and that's a human motivator.

"I really fundamentally want to live my life in this way, but the fact that I can walk away with tens of millions - that's a positive, I'm not going to say I feel bad about it. "

TerraCycle facts

Set up in the US in 2002

Launched in the UK in 2009

Has prevented 2.5 billion pieces of waste from going into landfill

Donated more than $6m to charities and schools

Makes money from recycling companies' waste, and selling it on to manufacturers

Also offers to make donations to charity when individual consumers send in recycled goods

The cigarette stubs it collects are turned into plastic pallets

Tom calls his social enterprise a meeting of communism and capitalism. As chief executive, he can only earn seven times the lowest paid employee. ("Seven X" as he refers to it.)

And everything about the business is fully transparent, he says, so every employee receives the same reports that he receives on the company's progress.

TerraCycle provides local bins for recycling

The offices are open-plan, and are usually based in cheaper parts of town - the US one is based in Trenton, New Jersey, and the UK one in Perivale, west London.

As part of the company's creative drive, it even has its own reality TV show - an excerpt of which, external shows the producer asking Tom if he could "stop talking in soundbites". He's nothing if not good at PR.

Of the challenges ahead for TerraCycle, he says a main one is keeping the large companies engaged.

"It's about organisations maintaining their desire around these [TerraCycle recycling] programmes, because everyone wants the next new thing," says Tom.

As for the individual consumers that send in stuff to recycle, he points out that they get nothing tangible in return for their service.

"You're buying a good feeling - so that's a harder product service to sell. There's a lack of physical payback. It's not like buying a coffee or knapsack. We're selling something esoteric."

Esoteric it may be, but investors are interested - Tom is in talks to sell a 20% stake with an unnamed British company for around $20m.