How much do women around the world pay to give birth?

- Published

Mariko explains how the cost of childbirth varies across the world

Money should be the least of your concerns when you are in labour.

But when I was about to push my baby out I noticed that the epidural was running low, and before asking my doctor to top it up I thought to myself: "Would that be another $500?"

Three days later I was presented with three different hospital bills; one for myself, another for our baby daughter and a third one, which I cannot even remember.

Mine was five pages long, detailing every item that I used during my two-night stay. Hers was not much shorter.

In total our first child's birth cost us just under $9,000 Singapore dollars ($6,650; £4,400). If you include all the pre-natal check-ups, the bill was well over S$10,000.

Mariko Oi with her husband Skye Neal and their baby daughter Miku Rose

Mariko's hospital bill: S$8,984.57

The biggest costs included:

Normal delivery with epidural: S$1,558

Hospital stay for two nights: S$1,060

Gynaecologist: S$2,247

Anaesthetist: S$550

Medicine: S$284.55

I am from Japan and my husband is from the UK. It would have been cheaper for us to start our family in either of these countries.

If we were Japanese residents the government would have given us an allowance, while in the UK we would have been covered by the taxpayer-funded National Health Service.

Here in Singapore, if you are a citizen, you get a baby bonus of S$6,000 and other subsidies as the government tries to encourage people to have more children to grow its population.

But as expatriates living in Singapore, we paid the full price for the medical treatment that we received.

Mariko's daughter Miku Rose at seven weeks

However, among our friends who also had their children in Singapore, S$9,000 is considered relatively cheap.

The birth of our daughter thankfully went smoothly, but any complications resulting in an emergency caesarean section would have more than tripled our bill.

US services 'a la carte'

But the $30,000 (£20,000) invoice that I was so afraid of is what an American woman gets billed on average for giving birth naturally. The total bill for a Caesarean section, meanwhile, tops $50,000, according to Truven Health Analytics, external.

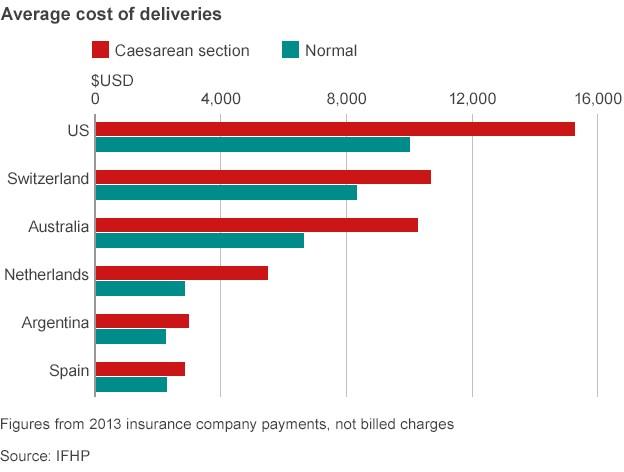

The delivery alone costs an average $10,000 in the US, while a Caesarean delivery costs over $15,000, according to the International Federation of Health Plans (IFHP), external.

The US is by far the most expensive place in the world to give birth or to receive any medical treatment as there is no publicly financed health services as in most developed countries.

Because prices are higher, patients receive more services, according to Prof Gerard Anderson of the Johns Hopkins Centre for Hospital Finance and Management. "If you can make more money as a doctor by ordering more tests, you are going to order them and therefore patients end up getting more tests," he says.

"You also pay a fee for services a la carte in the US so if you are worried about the pain of the childbirth and have an epidural, you'll have to pay for it. If you ask for a painkiller after giving birth, you'll have to pay for it. And all those costs rack up."

'Ridiculously expensive'

Take Mari Roberts, for example. When she gave birth to daughter Scarlet in November in northern Virginia, her total bill topped $100,000.

Mari Roberts just after she gave birth to her baby daughter Scarlet

"I had a planned Caesarean section due to my placenta previa (a condition in which your placenta is too close to your cervix) but I got admitted to the hospital a month earlier for restricted bed rest," she says.

"I was assuming it would cost around $1,000 a night but it turned out the hospital stay itself was $2,250 a night, which is ridiculously expensive.

"On top of that, we had to pay for everything. For example, an anaesthesiologist visited my room for a few minutes the day after I gave birth and that was $500."

Mari's hospital bill: $100,726.96

The biggest costs included:

Hospital stay for 30 days: $67,375

Gynaecologist: $4,100

Anaesthetist: $2,086

Ultrasounds: $1,200-$1,600 each

Blood tests: $750-$959 each

To her and her husband's relief, their insurance covered the entire bill.

But not everyone is so lucky.

Truven Health Analytics' research shows that on average women with employer-provided commercial health insurance found that their insurance covered just over half of their total bills.

The new Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, known as Obamacare, aims to extend health insurance coverage to people who lack it, including pregnancy and childbirth, but has been controversial.

"If you don't have health insurance in the US, hospitals and doctors will ask you to pay three to four times what someone with insurance will pay for the same service because no-one is negotiating rates on their behalf," says Prof Anderson.

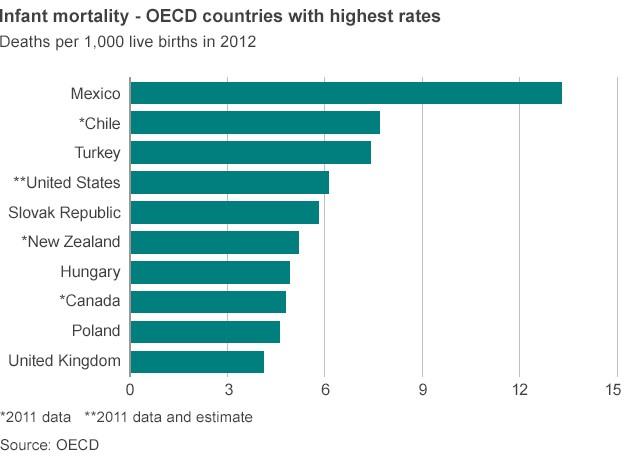

Despite the high price of healthcare, the US has a surprisingly high infant mortality rate compared with other developed countries - the fourth highest of the 34 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The OECD does note that the US rate may be higher than in other countries due to "a more complete registration of very premature or low birth weight babies", but also states that the reduction in the infant mortality rate has been slower in the US than elsewhere.

Of course the situation is very different in developing countries where simply getting access to effective healthcare is still an issue for many.

Lerato Mbele, BBC News, Johannesburg

South Africa's primary public healthcare system provides maternal care and ante-natal treatment that is generally free. However, it is quite a basic service.

About two years ago, there was a case of about six newborn babies dying at a public hospital on the outskirts of Johannesburg, because the hospital had run out of antiseptic soaps to clean the babies in their cots. Rural areas are even more vulnerable.

Women who are considered middle-class (about 30% of the population) can afford to have healthcare insurance and they use it for the best private hospitals, ante-natal therapy and specialist doctors. The average cost of having a baby in a private facility is about $2,000.

South Africa has one of the highest income inequalities in the world so the quality of birth is also a function of wealth and class.

With the history of racial segregation, that inequality also has racial overtones.

Some employers are offering flexible hours, home-working and daycare facilities

Shilpa Kannan, BBC News, Delhi

For poor people in India government hospitals are the main choice. Her, the tests, hospitalisation and delivery of your baby are free of charge.

For those who can afford it private hospitals come at a cost, though these costs can vary widely. Some start at 15,000 rupees ($240; £160) for normal deliveries, and 25,000 rupees ($400; £265) for Caesarean deliveries.

But most urban, working parents would choose hospitals that generally charge 75,000 rupees for normal deliveries and 200,000 rupees for Caesareans. This doesn't include the cost of check-ups, ultrasounds, tests during the nine months in the run-up to the birth.

For most middle-class working parents, medical insurance would cover up to 50,000 rupees of delivery costs.

The worrying trend in cities here is that birth by Caesarean sections have increased dramatically. Doctors and parent groups feel many of them are unnecessary and are mainly done because they are costlier and bring in more money for the hospitals.

'High-quality' healthcare

So is it possible to say which country has the best healthcare system?

Prof William Haseltine, president of ACCESS Health International and a former professor at Harvard Medical School, thinks the answer is France - which provides universal health coverage through social health insurance contributions from employers and employees.

Patients pay their medical bills and are reimbursed by sickness insurance funds.

"A uniform, high-quality medical service is available throughout the country and medical care is available to all, so no distinctions are made between rich and poor," says Prof Haseltine.

What about a close second? He thinks Singapore.

"It has a unique approach to finance healthcare through government subsidies, insurance, as well as a mandatory saving system," he says.

The compulsory saving programme is called Medisave, into which employers and employees contribute a certain percentages of their salaries every month.

"As a result, the government has managed to control national healthcare costs remarkably well by keeping it below 5% of GDP (gross domestic product)," says Prof Haseltine, who is also the author of Affordable Excellence: The Singapore Healthcare Story.

It also means that Singapore is better situated to handle an ageing population, which has resulted in ballooning healthcare costs in other developed economies.

There are still out-of-pocket payments to be made, however, which critics says are too high and make it difficult for low-income families.

Whatever the merits of Singapore's system, though, what works for a city-state of 5.5 million people may be difficult to replicate elsewhere.

For more on the BBC's A Richer World, go to www.bbc.com/richerworld - or join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag #BBCRicherWorld, external.

- Published3 February 2015

- Published3 December 2014