Why those at the top still need a helping hand

- Published

Leadership expert Steve Tappin says "the future of the company depends on getting this right".

Soon after he took the helm at drinks giant Diageo, Paul Walsh played an unusual trick in meetings.

The former chief executive used to pretend that he wasn't the boss, instead asking others what decision needed to be taken and who was going to take it.

His staff looked at him in amazement, having been under the assumption that he would.

"I'd say, 'I'm not capable of taking that decision. You know you should be taking that decision.'"

The approach, he explains, was an attempt to cut through "some of the bureaucratic noise" and make sure that people were confident enough to speak up and question things when they had more knowledge than him.

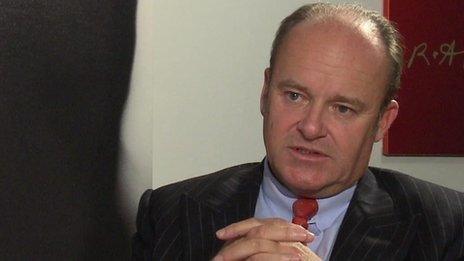

Paul Walsh looks for people who can make good decisions under pressure

"Sometimes the boss doesn't have all the right answers and has to modify their position. In the face of compelling evidence that's what should happen," he says.

As head of a multinational firm, operating in several different countries and employing thousands of staff, Mr Walsh's decision to delegate during his 13 years as chief executive seems eminently sensible.

But of course it only works if a firm has the right senior staff in place. Mr Walsh, now chair of catering giant Compass, says he has always looked for people that he thought would make the right decisions when under pressure.

"I expect capability, but I also want character. I consider this notion of a moral compass very, very strongly," he says.

Leadership expert Steve Tappin says recruiting the right top team is an area many chief executives spend a lot of time on because "the future of the company depends on getting this right".

Bosses can find it hard to keep their ego in check

But for chief executives, letting go of the reins when they've worked their way to the top isn't always easy.

After all, to get there in the first place will have required a certain amount of assertiveness and aggression, or even narcissism, not easy characteristics to subdue.

John Mackey, founder and co-chief executive of supermarket chain Whole Foods, likens the seductive dangers of being in charge to the ring of power featured in JRR Tolkien's fictional trilogy The Lord of the Rings.

"Chief executives have to be able to wear the ring of power and not have this need to be elevated above all else as if they were gods of some kind," he says.

He admits it's difficult, particularly for people at the top who will often have others telling them how great they are, and with their usually large salaries helping to boost their sense of self-importance.

Walter Robb (left) and John Mackey share the chief executive role at Whole Foods

Whole Foods has designed both its management structure and its pay to safeguard against these sorts of dangers.

Mr Mackey already shares the top job with Walter Robb, but the two of them are also part of seven member executive team. These senior staff all receive exactly the same salary, bonus and stock options as the two chief executives, and their salaries are capped at 19 times the average pay of a full-time worker.

Changes in how the firm is run are only made if the whole group agrees on them.

"Walter and I may be the leaders of that group but we all are working together," he says.

"Building grandma's house" is how Joe Plumeri describes his way of motivating staff

But this teamwork only works if all the team members understand exactly what they're working towards.

Joe Plumeri, the former chief executive and chairman of global insurance broker Willis, describes it as "building grandma's house".

In his 12 years at the head of Willis, he successfully returned it from private to public ownership and led its $2.1bn purchase of Hilb Rogal & Hobbs, one of the largest insurance brokerage deals of the last decade.

But when the American arrived as chief executive with his new ideas for the business, it proved a bit of a culture shock for the staff at the 200-year-old British company.

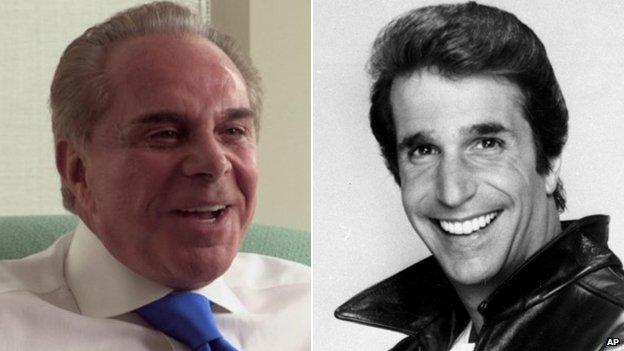

He said people looked at him as if The Fonz, the character in the US sitcom Happy Days, had turned up to lead the firm.

"I had a dream of a different company and a different era that wasn't the one that insured the Titanic," he says.

Joe Plumeri (left) and The Fonz

To get people to see his view for the firm's future, he used his "grandma's house" trick, which he likens to parents who build an exciting picture of ice cream, toys and cake in order to keep their children entertained on long car journeys, for example to see their grandparents.

"You've got to be able to paint a picture of a vision of where a company is going that is better than where they are now and the reason you do that is to get them to endure the trip because when they come to work every day they're going to have to do things that are different.

"They'll do all of that as long as they know where grandma's house is," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.