Luxury: Worth every penny?

- Published

Cheers. But why are we spending all this money?

Asked to define luxury, the head of one of the world's best-known luxury goods makers simply looked baffled.

"I wasn't prepared for that question. I'd need some time to think about it."

He could have said this: once you have met what you need to survive, you achieve a level of comfort. Beyond that is where you find luxury.

Beyond comfort is certainly on offer at Edmiston yacht specialists.

After all, if your clients are Roman Abramovich or Simon Cowell it would have to be.

Rory Trahair, Edmiston's head of marketing, says there are plenty of features to play with: "One of our top yachts, the TV, is 257ft long. It comes with four of its own boats, a swim-up bar and a crew ratio of more than two to each guest."

It has a helipad - oh, and the yacht's swimming pool can convert into a disco.

And it is beyond comfort, too, at carmaker Aston Martin, where it says "providing the request complies with legislation, anything is possible - from solid gold badges to a totally unique one-off car".

Raging demand

Is this on Tripadvisor?

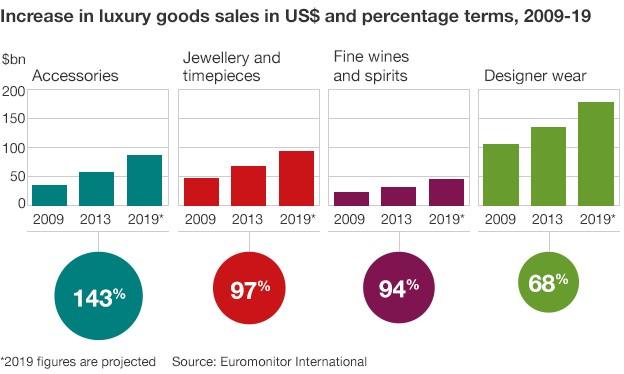

The growth of the global luxury market has been astonishing, and continues that way, from a collective $247bn five years ago, to $338bn (£224bn; €296bn) last year- a rise of some 36% - according to market data specialists Euromonitor.

Much of that demand had been coming from Russia, China and other fast-growing countries. But slowing development and Russia's political situation has put a dampener on that, says Fflur Roberts, global luxury manager at Euromonitor: "Social unrest and political conflict will have a major impact on what were fast-growing markets." So, she says, developed markets will begin again to provide the growth.

And that growth is impressive. Euromonitor is forecasting spending on luxury goods to be $463bn by 2019, an increase of 88% in 10 years.

Lustful glow

At Edmiston, its TV yacht costs €850,000 ($960,000; £630,000) a week to hire, while an Aston Martin's car can easily cost £200,000.

Despite the eye-popping prices of such outstanding items, they don't account for much of the $338bn worth of goods currently bought each year.

Things that don't hit the wallet so hard but speak of a rarefied, pampered world feature on many a gift list.

Individuals can stretch to afford a host of luxury goods, and the fastest growing category for the world's top producers are accessories - handbags, key ring holders, phone and tablet covers, and sunglasses.

The market for these is forecast to reach $86.4bn in 2019, a growth rate of almost 50%.

But take a handbag, for example. It's only leather, stitching and a few other bits and pieces, so why do the big, desirable names cost thousands of pounds?

Andy Milligan, founder of the branding consultants, the Caffeine Partnership, says such goods are carefully marketed to maximise the amount people will pay: "First of all you create the association with luxury and the brand. Then you create a price point at which people can afford to buy in.

"Armani has a number of different price points, as does Prada, Gucci and Tiffany. There are certain products, fragrance for example, they can make it a little bit expensive, beautifully designed and people can reward themselves with that."

As Tansy E Hoskins points out in her book, Stitched Up, this is the pyramid model favoured by the luxury houses: "A small number of luxury products like luggage and couture are sold to extremely wealthy customers, but the biggest profits are generated through the sales of 'mass-market' goods.

"Perfume and cosmetics are estimated to make up 55% of revenue for Chanel."

Affordability trap

But if a product becomes too popular, it loses its luxury appeal. After all, as Simon Peck, of House of Luxury, puts it: "When your chauffeur owns the same watch as you, it's time to look for something a little more interesting."

It's a strange concept that selling more goods is bad for business, but that's the pitfall for luxury providers. Let's call it the Burberry trap. The British trench coat maker lost control of its image in the 2000s, after football supporters and soap stars began appearing decked head-to-toe in its famous check fabric.

Burberry changed direction, employed cutting-edge designers and is now in the top 10 luxury brands in the world, worth $5.59bn, according to brand analysts Interbrand.

"I need a new watch"

'Enchanting universe'

Another way of maintaining allure, says Andy Milligan, is by creating the right atmosphere: "People who argue it's a product have a very strong case. But if you are buying a Burberry coat or a Tiffany item they are not sold as just a product - but as a luxury experience. You often do want to go to the special store and soak up the service."

As Jean Bienayme from upmarket jewellers Van Cleef and Arpels puts it: "Luxury is an experience we offer to our clients, immersing them in a magic and enchanting universe."

The biggest luxury goods companies by brand value:

Louis Vuitton $22.55bn

Gucci $10.39bn

Hermes $8.98bn

Cartier $7.45bn

Prada $5.98bn

Tiffany $5.94bn

Burberry $5.59bn

Ralph Lauren $4.98bn

Source: Interbrand, external

At Edmiston yacht hire it is also personal service, and not overt opulence, that is on offer, says Rory Trahair.

Still, the level of assistance throughout your hire surely beats anything on Tripadvisor: "Clients are given a dedicated assistant, they work with them, talk them through destinations, number of guests, for example, and we manage their travel from picking them up from home, to private jet, to getting them home again - and of course we're on hand throughout the charter to assist in any way."

Toasted treat

Peter York, management consultant and author, is sceptical about the whole concept of luxury though, and in particular those grand names.

Do they represent luxury? "Of course not," he snorts. "They're just brands."

He says simply: "Luxury is a business model. If you are a luxury brand, the thing that you make is the brand."

Real luxury, for him, does not have to bear a heavy price tag: "Real luxury is if you wake in the middle of the night and think, 'Oh I fancy some cheese on toast' and someone would do it for you - and not as a favour - and bring it to you on a nice tray."