Why Syriza wants a five-month cool-off

- Published

- comments

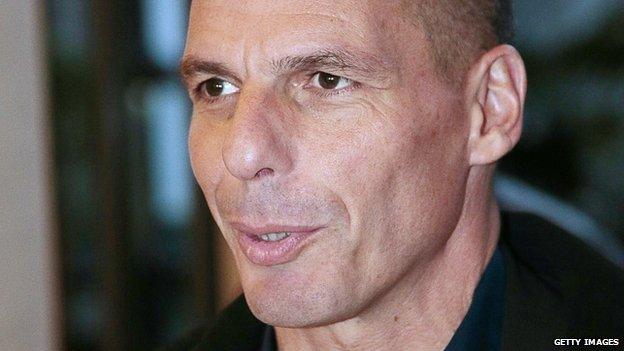

Greece's new finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has "a great deal of optimism for the future"

When I spoke to the Greek finance minister last night, Yanis Varoufakis said that he with his "left-wing heart" had much in common with the hedge fund managers and bankers he was wooing last night.

He told me: "It's a strange kind of alliance we are forging between a left-wing government and the financial sector... When you are in a debt deflationary cycle, putting an end to it both benefits the population by bringing it out of the clasps of misery and growing helplessness and increases equity prices."

Investors and populace would be ruined by endemically falling prices and stagnating economies that make debts harder to repay in Greece and in the wider eurozone, he told the meeting, held in the swanky Four Seasons hotel just off London's Park Lane. They had common cause in creating the conditions for his country and the wider currency union to grow again.

And as it happens, when I spoke to a couple of hedgies after it they were perhaps surprisingly sympathetic to his message - that the German insistence that Greece must stick to the austerity and repayment terms of its 172bn euro bailout, is wholly unrealistic.

What some may see as ironic is that the meeting was organised by that symbol of Germanic finance, Deutsche Bank. It is striking that this huge German bank wants to deal with the new Syriza government, but the German chancellor Angela Merkel is apparently very reluctant to meet the new Athens prime minister, Alexis Tsipras.

I wasn't allowed into the formal proceedings, but I watched afterwards as Mr Varoufakis was mobbed by assorted investors and bankers. "He is a bit of rock star," is how one analyst who was there put it.

Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis: "A bit of a rock star"

Probably the most compelling message that Mr Varoufakis makes is a "Nixon-goes-to-China" appeal.

He acknowledges that the Greek economy is still inefficient, inadequately competitive, hobbled by corruption. But he believes that only a brand new party like Syriza, even one on the left as it is, can be trusted to break up oligopolies and introduce more competition into product and labour markets.

How so? Well it is because he and his Syriza colleagues are outsiders, untainted by connections to the wealthy tax-avoiding elite, lacking in connections to corporate vested interests. If Syriza is in power for a year, it too will become captured by the kleptocracy, he fears, so he wants his government to reform swiftly.

His message therefore to Mrs Merkel is that he and she have more in common than she may recognise.

More than this, Syriza believes that Mrs Merkel recognises the truth in the recent speech by the governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, that a durable monetary union requires fiscal union - or a system for making transfers of resources from strong countries to weaker ones in a time of financial shock.

And perhaps the eurozone needs to go to the brink of disaster, precipitated by the threat of a Greek exit from the euro, to bring about the next necessary next stage in forging fiscal union.

Apart from economic reform, Syriza is also insisting it would run a budget surplus excluding interest payments - a so-called primary surplus - of between 1 and 1.5%.

And it would like to reconstruct its more than 300bn euros of debt, so that repayments are only made when the economy is growing properly again and are therefore affordable or not toxic to recovery.

But all this is still at the stage of broad brush principles. Syriza remains a million miles from the detail of debt reconstruction.

Perhaps the most important message Mr Varoufakis has been sending is that the government would like a five-month cooling-off period, when both it and its eurozone partners can draw breath and take stock.

Why does this matter so much?

It is big euro politics.

He knows that he won't just have Germany rejecting a compromise with Athens if matters are brought to a head before the Finnish general elections in mid April and the Spanish municipal and regional elections in May.

The Finnish government of Alexander Stubb is perhaps even more wedded to austerity and the obligation to repay debts than that of Berlin.

And as for Spain, well the point is that if Syriza wins eurozone permission to abandon austerity and ease its debt burden, Syriza's equivalent party of insurgents in Spain, Podemos, would be able to claim that only it could free Spain from the putative economic shackles imposed on the country by the rest of the eurozone.

Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy

So the Spanish premier, Mariano Rajoy, has to be seen to be denying Syriza any easing of the bailout strictures, lest Podemos enjoy a further surge in popularity.

In other words, to put country before ideology, Syriza has to help Rajoy - as far as it can - rather than its Podemos brothers in arms.