Euro's existential threat

- Published

- comments

The acrimonious breakdown of talks last night between Greece and other eurozone governments on a new financial and economic settlement for the debt-burdened country isn't just another swerve in the longest game of chicken in financial history.

It crystallises for the first time how much is at stake for Berlin and other eurozone governments, in the nature of what led to this latest impasse.

Because the fact that Berlin, Madrid, Lisbon, Dublin and the rest are insistent that Greece must agree to an extension of the current bailout, and its terms (however flexibly interpreted), goes to the heart of the matter.

For Germany et al the long-term success of the euro depends on the perception that its rules, and the applications of its rules, apply to all, in all circumstances.

If they create an exception for Greece, they fear they may find themselves obliged by politics and justice to revisit the austerity and hardship forced on Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus.

The euro would look like a hastily cobbled together monetary pact driven from pillar to post by economic expediency, with no reliable underlying governance structure.

Or at least so they worry.

And that would be the road to endemic economic and financial instability.

But there may be an even worse outcome for them from this impasse - which is that Greece could leave the euro.

That arguably would be an even more severe existential threat to the euro than bending the fiscal and financing rules for Greece.

Because in theory the euro is forever. That is what all the law associated with it says.

And once it is not forever for Greece, it is not forever for any nation, even Germany.

Whether Berlin likes it or not, the moment Greece leaves, those who control the world's huge pools of liquidity or cash will start placing bets on the next country to head for the exit.

Once that happens, eurozone fragmentation is almost impossible to reverse: the vast and widening gulf in access to global capital between vulnerable and stronger eurozone economies would reinforce their diverging economic performances.

Gamble

As the rich north became ever richer relative to the over-indebted south, a more devastating eurozone breakup would become almost inevitable.

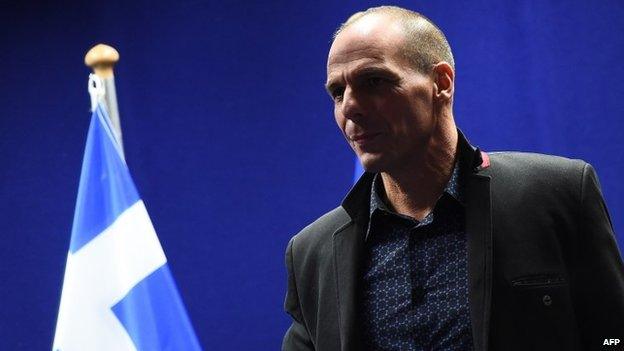

So, it is the big gamble of Greece and its finance minister Yanis Varoufakis that its exit will ultimately be seen by Berlin as the bigger existential threat.

To be clear Greek exit is also an existential threat for the Syriza government, given that most Greeks say they want to keep the euro.

But Syriza can be confident Greece would endure if Greece leaves the euro, although the country would be considerably poorer for a while.

By contrast, Berlin, Paris and the rest simply cannot be confident the euro will be for all time if Greece is either bundled out the exit door or chooses to walk through it.

Because it would demonstrate that the euro had failed in its core underlying purpose, which was to bind its members ever closer together, economically, financially and - perhaps critically - in a political sense too.