Heat pumps extract warmth from ice cold water

- Published

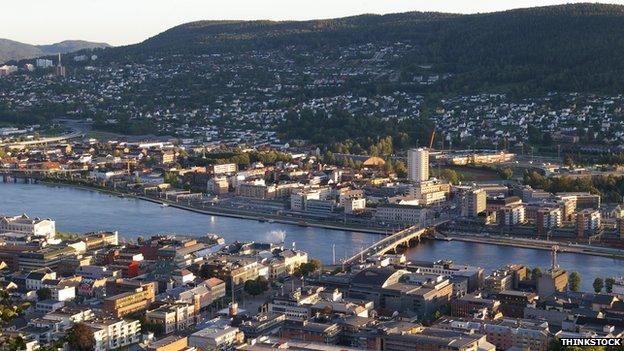

Drammen's ice cold fjord is not an obvious source of heat for the city's inhabitants and businesses

The residents of Drammen have rather an unusual way of keeping warm.

The county capital, 40 miles west of Oslo in Norway, extracts most of the heat needed to insulate its houses, offices and factories against the biting Nordic cold from the local fjord, or more precisely from the water held within it.

Averaging 8C throughout the year - it's literally cold enough to take your breath away. So cold, in fact, that open water swimmers classify it as freezing.

But somehow, an open-minded district heating company backed by an environmentally-conscious city council, together with a large measure of Glaswegian nous, has built a system to meet the heating needs not just of Drammen's 65,000 residents, but its businesses as well.

Growing popularity

There's nothing new in heat pumps per se, but the technology has advanced greatly since the first examples dating back to the 19th Century.

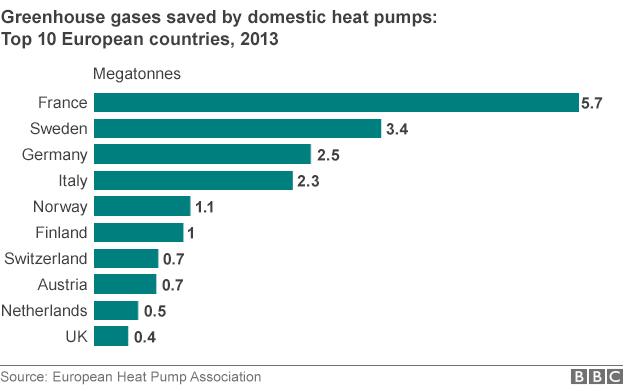

There are, for example, hundreds of thousands of heat pumps sold in Europe each year, while there is a burgeoning market in China, Japan, the US, New Zealand and Turkey, according to Dr Roger Nordman at the International Energy Agency's Heat Pump Centre.

But the vast majority of these are air and ground-source pumps fitted to individual homes, and with ground pumps costing upwards of €15,000, the costs are substantial. Air pumps also suffer from greater variations in ambient temperature, and are less effective in winter.

In some countries, they have also suffered from bad press. In London, for example, there was a rush to install heat pumps in the late 1990s as a box-ticking exercise to meet new renewable energy planning regulations. In many cases, they were completely inappropriate.

As Prof Paul Younger at Glasgow University says, "if you get a monkey to design a car it will be crap, but that doesn't mean the car itself is a bad idea".

For various reasons, then, heat pumps remain one of the less well known clean energy technologies, says Dr Nordman.

And particularly water source heat pumps, which hold a number of key advantages - they cost a lot less than ground pumps because no digging is involved, and as water maintains its temperature much better, they offer more consistent performance than air pumps.

By combining this with a district heating system, where one plant can provide heat for an entire community, the technology can produce quite staggering results.

'Pushing boundaries'

By 2009, Drammen's population had grown to such a degree that its existing district heating system could not cope.

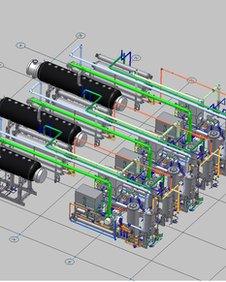

Star's pumps provide most of the hot water needed to heat the whole city

While researching ways to expand its capacity, the city's heating company, led by Jon Ivor Bakk, discovered the water temperature in the fjord was ideal for heat pumps.

If it could make the system work, the company would no longer need to buy in and burn dirty fossil fuels - primarily gas - to generate heat.

It began a tender process and one company immediately stood out - Glasgow's Star Renewable Energy, best known for providing refrigeration systems to some of the UK's biggest retailers, including Tesco and Asda.

In fact, the company had no experience of water-sourced heat pumps. As director Dave Pearson says, "we were the new kids on the block but we've always had a reputation for pushing boundaries".

The selling point was simple - while other companies were using hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), a potent greenhouse gas that is being banned by the EU, as the coolant, Star proposed using ammonia, which contains no carbon.

How the Drammen heat pumps work

Water from the fjord at 8C is used to heat liquid ammonia at four times atmospheric pressure (4 bar), till it boils at 2C and evaporates

By increasing the pressure to 50 bar, the evaporated gas is heated to 120C

The gas is then used to heat the water in the heating system from 60C to 90C (the water goes out of the plant at 90C and comes back in at 60C)

Once the heat has transferred to the water, the ammonia gas changes back into a liquid state

The process begins again

By the beginning of 2011, Star's heat pumps were providing Drammen district heating with 85% of the hot water needed to heat the city. In fact, the system has exceeded all expectations - "we are very happy with it," says Mr Bakk.

Having already paid for itself, and with annual savings of around €2m a year and 1.5m tonnes of carbon, the equivalent of taking more than 300,000 cars off the road for a year, it's not hard to see why.

Saving money

Heat pumps are far less energy intensive than other forms of heating - providing 3KW of thermal heat for every 1KW of electricity, three times as much as you get from electric heating.

Mr Bakk and his team have won awards for the Drammen project

And because electricity is so cheap in Norway, one unit of heat costs 1 pence, compared with 3p for biomass, 5p for gas and almost 8p for oil, according to Star. In fact, Mr Bakk says his company would be losing money if it used only biomass.

The system has one other major advantage over conventional heat pumps - it can heat water up to 90C rather than the usual 50C-60C, which means it can be used in old as well as new buildings. For the first time, retrofitting homes that use gas-powered boilers to drive heating systems that require very hot water becomes a realistic possibility.

Of course heat pumps are only zero carbon if they are powered by clean electricity, but they are cheap, clean in terms of CO2 emissions and local air pollution, and sustainable.

Using ammonia instead of harmful HFCs would appear, then, to be the final step towards making water-sourced heat pumps a viable alternative to gas and electric-powered heating systems. "Star has done a very nice job in providing a good, sustainable solution," says Dr Nordman.

Or as Prof Younger puts it, if any questions remained about this kind of technology, "Drammen nails it beyond any reasonable doubt".

Huge potential

And if it works in Drammen, it can work anywhere there is a constant supply of water, standing or flowing.

In the UK, Star is already working with local housing associations in Glasgow and is speaking with a dozen city councils including Newcastle, Durham, Manchester and Stoke. It is also working on projects in Zurich and the South of France, and bidding for a system in Belgrade.

The Drammen water-sourced heat pump project is the biggest of its type in the world

The potential is clearly huge. For example, the company calculates that the Thames river could generate 1.25GW of capacity, enough to heat 500,000 homes.

There are a number of barriers to widespread adoption in the UK, from weak local government powers and a lack of heating networks, to a complex, privatised energy market and fear of the unknown.

But as Doug Parr at Greenpeace UK says, "there are no easy ways to decarbonise heating, but I'm mystified as to why there are not more [heat pumps in the UK]".

Especially when the technology exists, not just to extract heat from water, but to harness waste heat from all manner of sources, from factories and data centres to power stations and industrial processing, boosting efforts to wean ourselves off fossil fuels and reduce CO2 emissions.

"We are slowly waking up the idea that we don't need to burn new fuel to heat things up, we can harness heat in the local environment," says Mr Pearson.

With about 40% of all global energy used by buildings, and much of that for heating, the sooner we wake up the better.