Japan's seaweed harvesters miss out on growth plans

- Published

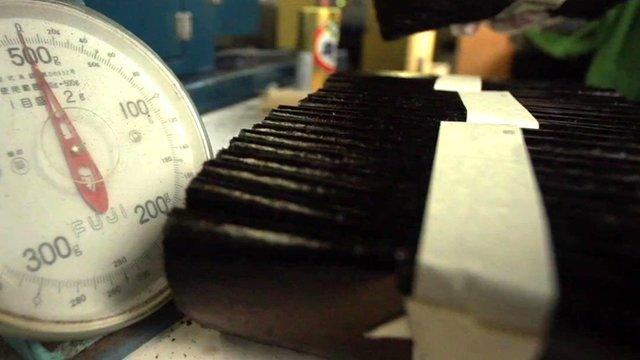

WATCH: Futtsu's seaweed processing industry is struggling

"The entire nation seems excited about Abenomics," says Toshi Koizumi, the president of the Shin Futtsu Fishery Association, "but an industry like ours is not feeling the benefit at all."

Seaweed harvesting is the city's biggest industry. Futtsu is less than two hours' drive away from the capital Tokyo, but despite this the locals - mainly fishermen - feel left behind by the recent economic upturn.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's programme of economic stimulus - nicknamed "Abenomics" - seems to have passed by Futtsu.

Today there are other seaweed providers, business is getting tougher for the industry which is in decline.

"We are competing against China and South Korea," says Mr Koizumi.

"A free trade deal that the government wants to sign would seriously threaten us."

During our visit, in the darkness before the dawn, the fishermen and women are gathering around bonfires. At the edge of the water, more than 100 boats are anchored before setting out for the daily catch.

Seaweed harvesting is the main industry in Futtsu, Chiba

As the sun rises upon their return, I can see the faces of the fishermen and women more clearly. There are a lot more wrinkles than I had expected.

Men and women who could be old enough to be my grandparents are carrying baskets full of the edible seaweed, nori. It is an ageing industry where people are struggling to find successors.

It is also costly. The machinery required to process the raw seaweed into dried sheets costs $200,000 (£130,000) a unit. What used to be done manually for centuries is no longer economically viable.

"No matter how high our costs go, we don't get to sell the finished product at a price of our choice because it gets ranked and auctioned," says Mr Koizumi.

In the 1950s, farming - including seaweed harvesting and fishing - once employed half of Japan's workforce. But as the nation industrialised it has long been in decline and today accounts for less than 4% of the nation's workforce.

Tax hike

Last year's rise in sales tax from 5% to 8% has affected sales.

"Of course, it affects our sales," Hiroshi Nakazawa tells me in his small store. When he started selling seaweed 40 years ago, there was no sales tax to factor in.

"Customers get used to it after a while but I can feel that they have been tightening their belt," he says.

"When I took over this store, customers didn't hesitate to spend money, but now, there is a gap between rich customers who can still spend money and those who cannot."

Seijiro Takeshita, a strategist at Mizuho International, says the sales tax hike came at a bad time.

The fishermen say any free trade deal would seriously affect the industry

"Not many thought that the hike from 5% to 8% was such a big deal but it was. You can now see clearly how the fragility of Japanese consumers was negatively affected."

The government says these sales tax rises are necessary to tackle Japan's ballooning debt, which is more than twice the size of its economy.

"We are at an untenable situation where we have to pay interest on this debt," says William Saito, a special advisor to the cabinet office. .

"I think it is important for Japan which had a very low consumption tax to raise it to pay down its debt for the future."

But at the same time, the government plans to cut the country's corporate tax to below 30% in several stages starting this year - which critics argue is one example of Abenomics only serving the rich and the powerful.

"For Japanese companies to be taxed, they need to be making money and frankly, not many have been profitable for many years," says Mr Saito.

Mr Takeshita sees the cut in corporate tax as a way to give Japanese firms some 'elbow room' to invest in their businesses.

The hope is that more investment by Japanese companies would bring about "a lot of other economic activities in Japan because it will result in job security, a pay rise, then consumer spending," he says.

There had been fears a higher sales tax could hurt domestic consumption

Bankrupt city?

But places like Futtsu are outside of this economic cycle.

Before returning here to run the seaweed shop that his late father opened, Mr Nakazawa worked as a salaryman in Tokyo and he remembers Japan's economy at its peak.

"Big cities may get a boost from Abenomics but we are losing young people in Futtsu which means the city will get less tax revenue," he says.

On the same street where Mr Nakazawa's shop is located you can see stores that have been shut for many years, overgrown with plants and shrubs.

By Japanese standards, the city looks run-down, or at least to someone like me who was born and bred in Tokyo.

My cameraman and I went to Futtsu because it warned last year - it might run out of money by 2018.

If Futtsu does become bankrupt, it would only be the second city in Japan to do so after Yubari in the northern island of Hokkaido.

Yubari declared bankruptcy in June 2007, with debts of more than 35bn Japanese yen (£150m; $231m). Six years later Yubari had paid back 3.8bn yen of its debt and has set a 2030 deadline for full repayment.

Unlike Yubari whose economy has been in decline since its heyday as the capital of coal in the 1960s, Chiba has always been known to those familiar with Japan as the "New Jersey of Tokyo."

With its proximity to Tokyo, not many thought one of its cities' economies could be in such trouble.

Japan's economy slipped into a recession months after the sales tax hike was imposed

Growing disparities

When I was growing up in the 1980s, there was a saying that the entire nation was middle class.

But in the last decade, the belief about egalitarianism has been challenged. The word "kakusa" or disparity has been used frequently, and now, more so than ever.

The supporters of Abenomics say real and lasting improvement will soon be seen in the real economy and that is certainly the hope of fishermen here.

"I think it is our mission to pass this tradition of seaweed harvesting to the next generation," says Mr Koizumi, whose son is continuing the family business.

"I hope the prime minister will also think of us in the primary industry which is at the foot of the society."

- Published24 February 2015

- Published16 February 2015

- Published14 July 2014

- Published8 December 2014