The reality of becoming your own boss

- Published

At the early stages of launching a business it's all about building credibility with customers, employees and partners

Becoming your own boss is many people's dream. The appeal seems obvious - complete freedom over how you organise your time, and only having yourself to answer to.

A host of recent multi-billion dollar deals for small start-ups, particularly in the tech arena, have helped fuel many people's dreams.

Facebook paid a cool $19bn (£11.4bn) for messaging app WhatsApp when it had just 50 employees and had only been in existence for six years.

The internet giant also paid $1bn for photo-sharing smartphone app Instagram, which was less than two years old and had only 13 staff.

Similarly, Yahoo shelled out $1.1bn for blogging service Tumblr, founded just six years earlier.

Big deals for start-up firms, like WhatsApp, are rare, with most new firms failing

Successes like these make it tempting to think that with the right idea serious wealth is just around the corner, yet the stark truth is that most start-ups fail.

In fact, the majority (55%) of British small and medium-sized enterprises don't survive more than five years, according to research from RSA, external, the UK's largest commercial insurer.

And ditching the day job to start up your own business is rarely as glamorous as it sounds.

'Really competitive'

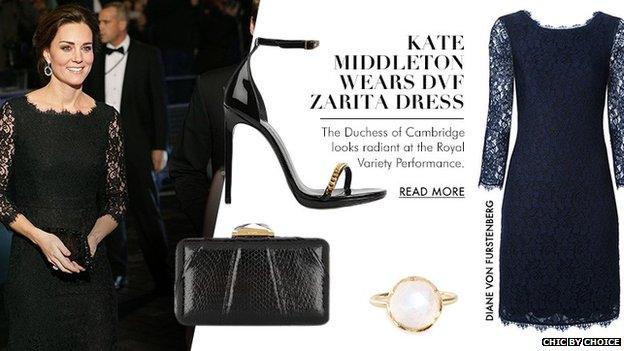

Filipa Neto is co-founder of Chic by Choice, an online marketplace which rents out designer dresses, enabling people to hire rather than buy them.

Ms Neto, originally from Portugal, says she and co-founder Lara Vidreiro came up with the idea after struggling to find dresses for formalwear events when they were not willing to shell out hundreds of pounds.

Chic by Choice rents designer dresses sourced from well known brands

She says her parents were initially sceptical of her idea.

"In the beginning, they were like 'what are you doing with your life? Why are you not going to a consulting company or working for McKinsey, Deloitte or KPMG?'," says Ms Neto.

"Those were the expectations for someone who went to a really good university in my country."

The business launched in June last year and is not yet profitable, but so far it has 230,000 customers from 15 countries across western Europe, and its transactions are increasing by 30% each month.

But Ms Neto says it is difficult to persuade more well-known designers and established brands to join her database of suppliers.

"It's really competitive. So even when I do an approach that is really targeted I know there are a hundred other people trying a targeted approach as well."

'Delicate balance'

Leadership expert Steve Tappin says start-up firms like Chic by Choice should assume a 90% failure rate when trying to get big firms on board, with only a minority of the most pioneering large firms willing to do any kind of tie-up with a new company.

"Their fear is of making the wrong decision and getting into trouble with the hierarchy, that's for most corporates unfortunately the situation."

WAYN aims to help people discover where to go on holiday next

However, he says there are "four elements of trust" which any start-up founder can work on to help persuade a large firm to support them: making some kind of personal connection, ensuring their motivation behind the business is genuinely convincing, proving they have the ability to deliver consistently and making sure their way of doing business is compatible.

But even once a start-up has persuaded larger firms to come on board either as part of a partnership, or by way of an investment to help it expand, working out how big a share of the firm to give away as part of the deal can be difficult.

Peter Ward is co-founder of WAYN, an acronym for Where are you now?, a social network aimed at connecting travellers and helping people discover where to go and what to do in new places.

It's already profitable, with a presence in 193 countries and more than 23 million members, but Mr Ward has bigger ambitions, wanting the firm to be valued at $1bn. Yet getting the right investors on board to help it drive this expansion, but still managing to keep overall control is a "delicate balance", he says.

"The trade off is you want to raise more but obviously maintain the control, which in our case is board control as well as equity majority. One of the things that plays on my mind is do we have enough financial support to play against the big guys?"

Lemonaid Beverages gives 5p from each bottle sold to its charity

To address this, Mr Ward says he is focusing closely on people's perception of the firm.

"The key is to get the balance right, where you can show momentum, you can show that you're doing something unique, that has the potential to be huge," he says.

Carving a niche

Julian Warowioff is UK managing director of German start up Lemonaid Beverages, a soft drinks firm using organic and fair trade ingredients, where 5p of each bottle purchased goes to its charity, and which aims to help disadvantaged communities globally. He says competition with bigger firms is also a challenge.

"We are still a very small company compared to our competitors, which have really big marketing budgets which we can and will never have," he says.

Julian Warowioff says it is not targeting the big supermarket chains to sell its drinks

However, instead of trying to directly compete, Mr Warowioff says Lemonaid Beverages is trying to carve out its own niche using word of mouth, and trying to spread the word about the company and its charitable projects by attending music festivals and similar such events to meet potential customers directly.

"As we do not have shareholders in the company that ask for a profit margin on their investment we're pretty free to choose how much we want to sell, where we want to sell," he says.

"For us that means we'd rather supply the small individual artsy cafe bar restaurant scene, the corner stores, the organic wholefood stores, rather than the big supermarket chains."

In the end, the biggest determinant of success for a start-up firm, says Mr Tappin, is how convincingly a founder is able to convey their own excitement about the business.

"They've got to love their business. It's got to be connected to them and it's got to be meaningful for them. If they can create the same passion in investors then the sky's the limit," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.