Is the samba slowing for Brazil's middle class?

- Published

Years of economic growth have lifted millions of Brazilians out of extreme poverty. But as the economy stalls, are the gains of the new middle class now at risk?

On a warm evening in mid-February, Cleide de Melo and her daughters are preparing a large, festive dinner for visitors on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Fifty-three-year-old Cleide grates onions and carrots for a cheese souffle, while her daughters Daniele and Vanessa, 34 and 23 years old respectively, crowd around the stove, making chicken fricassee and couscous.

The de Melo family tells the story of both perseverance and mobility. And it's one that reflects a larger journey of Brazil's middle class over the past decade. A middle class that has grown to almost 50 million people, yet is threatened by a stalled economy, rising inflation, and consumer debt.

Cleide de Melo came to Sao Paulo in 1985 as a pregnant 17-year-old, when her parents banished her from their house in Recife, in northern Brazil.

Happy family: Vanessa, Cleide, Eleonora, Joao and Daniele

She had no money, and had to leave her baby Daniele behind with a sister in Recife. She worked as a maid, a cleaner, and a caterer. Now she has five adult children, and paid down the debt on her home over the course of a decade.

"It was the greatest joy of my life," she says of the day she paid off the last debt on her house. "I did everything I could to leave this home to my children."

Through Cleide's hard work, her children have opportunities their mother never had.

Daniele is a housewife and mother in Recife to Joao, and sends him to private school. Eleonora, 26, works at a high-end boutique in Sao Paulo, and is studying to become a makeup artist. Vanessa is in dental school. And Cleide's 18-year-old son Lucas is studying engineering and labour safety. A fourth daughter does not keep in touch with the family.

While Brazil has many social programs to alleviate poverty, Cleide de Melo felt strongly that her rise out of poverty has been solely a result of her own effort.

"I am the government," she says with a laugh. "I had five children and the government helped me out on nothing. Ok, nobody asked to come to this world, so I had to take responsibility for my children and I did."

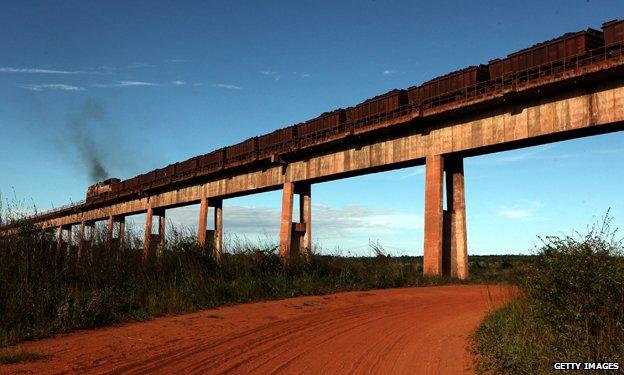

Iron ore exports helped fund Brazil's social domestic policies and fuel growth

The family's path to the middle class mirrors the rise of tens of millions of Brazilians in recent years.

In the early 2000s, Brazil began exporting many of its commodities - such as iron ore, soy, and beef - around the world, fuelled by growth in places like China and India.

Those commodity profits, according to Hector Gomez Ang of the World Bank's International Finance Corporation, kicked off a virtuous cycle.

"That started creating jobs," he says. "That's one of the factors."

Those jobs then drove a need for services, health care, and education.

Added to that, says Gomez Ang, was a state policy where the government pushed banks to offer credit to consumers at favourable terms for the first time.

"That also fuelled consumption," he adds. "People could start buying stuff, and that sort of fed into the overall production.

"So that if you were buying refrigerators and the refrigerator company was selling more refrigerators than ever before, that created jobs and so on."

The combined effects of this boom lifted 50 million Brazilians into the middle class between 2003 and 2014, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In addition, direct government payments to the poorest of the poor, known as the Bolsa Familia, helped alleviate much of the worst inequality in the country.

Bolsa Familia has been credited with lifting many out of extreme poverty

But dark clouds are gathering. With the economy now stalled and potentially headed for recession, the good times may not last for the middle class.

Many Brazilian families bought on credit over the past decade. The typical family spends about a fifth of its income just paying off debt, says Gomez Ang.

That debt, plus the tenuous nature of the past decade's economic and social progress have made some experts worried.

"The present predicament of Brazil is whether Brazil will prove that the social gains are sustainable," says former finance minister Rubens Ricupero. "And it's very doubtful. Because [for] almost three years Brazil has grown very little or nothing at all."

Ricupero fears the country is already in recession, and says the latter half of 2015 will hit middle class Brazilians particularly hard.

Add to that a corruption scandal at Brazil's largest company, Petrobras. Executives at the state-run oil firm are under investigation for taking bribes and funnelling money to the political party of President Dilma Rousseff.

Eleonora and her younger brother Lucas

Even at dinner in the de Melo household, Petrobras casts a shadow. "It's devastating for Brazil," says Lucas. "It's the money being siphoned out [and having a] negative impact for the market."

"And it causes unemployment," adds his older sister Eleonora, cautioning her younger brother about his chances of finding work after school.

Still, the family is philosophical about what is coming next.

A rough patch in the economy was not unexpected, says Eleonora, who already saw customers at her boutique buying less. "Now they are afraid to spend," she says.

But following their mother Cleide's example, all the children are certain that no matter what the Brazilian economy held for them in the short term, they are determined to make a better life.

"I wake up and thank God," said Eleonora. "I feel I've got to go to fight to work to accomplish my things."

Listen to more about Brazil's economy on Saturday 28 February at 08:30 GMT on the BBC World Service

For more on the BBC's A Richer World, go to www.bbc.com/richerworld - or join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag #BBCRicherWorld, external