Banking on it: Taking your money off the high street

- Published

Decided that retail banking is the devil? You could opt for a piggybank. Or you could try the new online only services claiming to have changed the humble bank account forever

In Durham, Atom Bank is poised to launch shortly as a bank with no branches, living solely on the internet.

The US has Ally Bank, an internet-only bank focused on its smartphone interface.

China recently has launched an internet-only bank of its own, WeBank, led by gaming and social network group Tencent Holdings.

With British and US retail banks in low repute since the credit crunch, the field is ripe for nimble new entrants, unencumbered by physical branches, bad loans, and ageing infrastructure.

Meanwhile, many British banks continue to operate back-end systems in pounds, shillings, and pence.

And a botched 2012 attempt at an IT upgrade by the RBS group left 6.5 million people unable to make payments for up to three weeks.

Nudging open the teller's window for new competition: banking scandals, rate-fixing and payment protection insurance, and bankers' bonuses have played their role, too.

The bank of the internet is increasingly open.

The global financial crisis left some people disillusioned with mainstream banking

Banks losing interest

And you no longer need to be a bank to offer a bank's services.

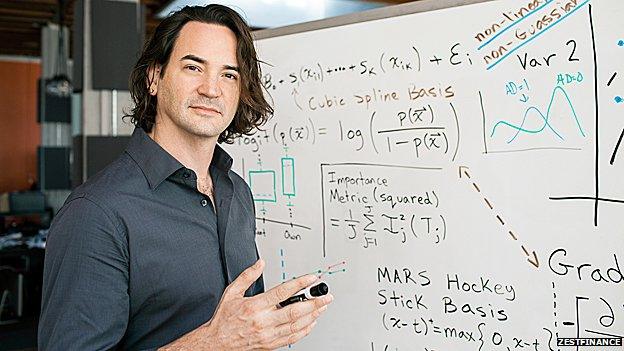

Former Google vice-president Douglas Merrill's ZestFinance uses similar maths to the search engine to offer a big-data approach to underwriting payday loans.

With banks still a bit frugal with lending, AvantCredit, a 2012 personal loans start-up active in the US and UK, uses machine learning and a host of big-data variables to identify worthy near-prime borrowers.

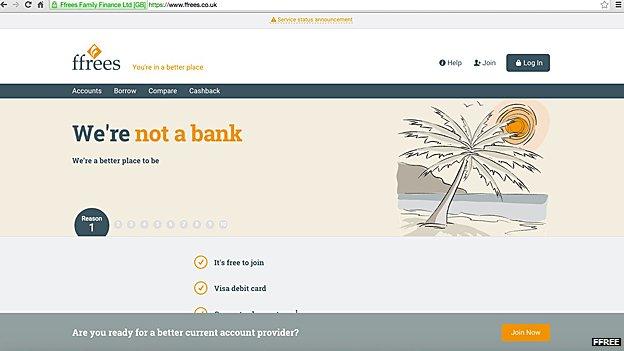

And Sheffield-based Ffrees offers current accounts without being a bank (but a 75p withdrawal fee).

Each company says it can provide one of retail banking's key services better than the banks themselves.

Popping down to the bank to deposit your silver is now not so much of a common occurrence

AvantCredit's chief executive, Al Goldstein, says his two co-founders were former interns of his, who attempted to get a loan at a physical bank branch.

"And the experience was so terrible. I thought, it doesn't need to be, and we had the ability to work something new."

He says his company's current models use nearly 500 individual variables to predict the propensity of an individual consumer to default.

"The key is to aggregate as much data as possible," he says, "the better our predictive modelling capability is, the cheaper price we can offer to an individual customer."

AvantCredit's chief executive, Al Goldstein, left

The AvantCredit team at work

Alex Letts, Ffrees's chief executive, says "You won't find me saying banks are crooks - wrong; they have a problem, they can't make money."

By offering current accounts for free, he says, retail banks lose money on the vast majority of them.

"It's not a good model - 60-80% of the bank's customers are people out of whom the banks only make money by charging for their mistakes or helping them get into debt."

"This creates the foundation for a quite adversarial relationship," he adds, "and this all blew up in the miss-selling scandals."

It was the unprofitability of most personal banking, not payday lending, that caused the last banking crisis, he says - and it hasn't gone away.

The challenge, then, is "finding a way of being able to say to people, you have to pay for this stuff, man up, it can cost you up to £10 a month to run a current account, but won't cost you any more," as opposed to making profit by sleight of hand.

The answer, he says, is thinking of a current account as data.

"It's a spreadsheet, sitting on a mainframe somewhere - there is no pile of gold in a vault that is associated with you."

"What you need is something to provide a very slick spreadsheet manipulation technology, to give you an amazing experience, and help you manage this little pile of poo that is your money, that causes you so much stress in life, and get you to a better place."

Alex Letts on your current account: "It's a spreadsheet, sitting on a mainframe somewhere - there is no pile of gold in a vault that is associated with you."

Ffrees is not a bank (although it is regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority) - but offers current accounts with a 75p withdrawal fee

You're not a loan

If Mr Letts says retail banks' personal current accounts are unsustainable, ZestFinance's Mr Merrill argues the maths behind their loans are 60 years out of date.

In the 1950s, says the former Google vice president, the application of new maths - logistic regression - to credit bureau data, offered a standardised way of offering credit, and expanded the amount of available with mass social impact.

But logistic regression is hypersensitive to data that is missing or wrong.

As a result of data being slightly warped, he says, "people are given very low credit scores and being priced out of the credit market unfairly. I look at that problem, and it's a maths problem."

Google's indexing algorithms have learnt to be resilient against misspellings and missing words.

He says applying similar strategies to those he had used at Google to cope with erroneous or missing data permits his company to recognise good credit risks in the great swathe of those who aren't.

ZestFinance's Douglas Merrill says banks methods of credit scoring are 60 years out of date

The ZestFinance offices

We have seen internet banks before.

In the first dot com boom, the web-only bank First-e launched in September 1999, operating from Ireland under a licence from a French bank.

It succumbed to the ensuing collapse of the internet bubble, while others were purchased by retail banks.

Atom Bank's chief innovations officer, Edward Twiddy, says they were limited by being 'just a browser experience', and those bought by banks received too small investment afterwards.

"I had a First-e account and it was good value, but it was just sort of what it was, a thing for holding cash in, and not particularly titillating," he says.

Mr Twiddy describes current internet banking as not having evolved very far since then, and "going through several layers of authentication, and that's where you are until you leave."

He says Atom is working on designing "more horizontal customer journeys", and says other banks have underinvested in their delivery mechanism.

"They spent 20 years doing quite nicely out of a model that ultimately proved to be not sustainable."

The team behind Durham-based Atom Bank

Works hard for the money

For new entrants like Atom seeking to become banks, manoeuvring through regulations and raising capital is difficult.

"It's a long burn," he says, with a lengthy pre-application engagement with banking regulators the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority.

"The regulator sets us homework to do, marks our homework, asks us to hand in our exercise book at the end, then goes away and says subject to these restrictions, we will authorise you," he adds.

"It hasn't been easy but it hasn't been hugely unpleasant."

In the US, internet-only Ally Bank's parent company Ally Financial failed the Federal Reserve's 2013 stress test thanks to concerns it lacked enough capital to weather an extreme economic downturn.

Ffree's Mr Letts says new ventures like Atom Bank remaining within the retail banking model is the "final sharpening of the pencil to make a point, after which you can't sharpen it any more". He predicts in five to ten years, half of current accounts will not be in the major retail banks.

"And major retail banks will be doing what they're brilliant at - providing infrastructure, managing mortgages, all that sort of stuff."

Yet fintech accelerators like Barclays's in East London and large new funds from Santander and HSBC shows that high street banks recognise the need to jettison legacy systems and learn from innovative start-ups.

So for there to be continued profit in big banking, there also will have to be a little small change.