Is fibre optic cable key to Africa's economic growth?

- Published

In the developed world fibre optic cables like this are what keep many people connected

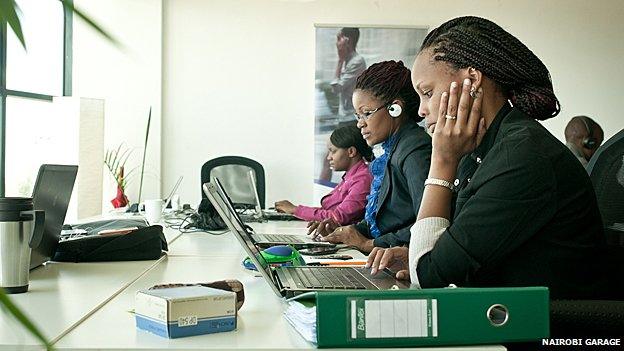

The elite of Kenya's much-heralded entrepreneurship revolution work in an ultra-modern. co-working space overlooking the bustle of Nairobi.

Their businesses are reliant on the high-speed internet available here.

The Nairobi Garage is one of a limited number of work spaces in the city boasting a dedicated 25 megabits per second [Mbps] fibre internet connection.

Fibre is definitely not the norm in Kenya - a country viewed as a leader in African technology innovation. In financial terms, fibre internet is way beyond the grasp of most entrepreneurs and small businesses.

A 25Mbps connection costs in the region of $4,000-$5,000 (£2,700-£3,380) a month.

Nairobi Garage is one of the tech hubs that have made the Kenyan capital a technology powerhouse

Pulling together

"Tech is taking off in Kenya thanks in large part to the arrival of fibre internet - unfortunately the cost of this to companies is still extremely high.

"Large companies like banks can afford the prices of corporate internet, but for start-ups and SMEs [small and medium sized enterprises] the costs are crippling," says Hannah Clifford, general manager at Nairobi Garage.

Over 100 small businesses have started out life in the communal work space, which currently accommodates 30 start-ups all using the stable high-speed internet connection offered at a subsidised cost.

"Through shared work spaces like Nairobi Garage, which is aimed at supporting the start-up sector, young businesses and entrepreneurs are able to get internet access as part of their office space at very affordable rates.

"High-speed, reliable internet is vital for these young businesses to compete with the likes of Silicon Valley," she says.

A decent internet connection is vital to the success of many start-ups

'Human right'

Companies such as Liquid Telecom are working to make fibre internet a reality across Africa. By the end of the year it will have spent about $500m (£337m) laying more than 18,000Km of fibre cable on the continent, making it the owner of the largest fibre network in Africa.

It has also started working on providing fibre-to-the-home - a service now beginning to be enjoyed by some customers in Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Chief executive Nic Rudnick is convinced that fibre roll-out is a human right as well as a business necessity. He says the "backbone" Liquid is laying will contribute to Africa's economic growth.

"Liquid Telecom was founded based on a conviction that telecoms connectivity is now a basic human right. We've devoted a tremendous amount of time, strategic thinking and good old-fashioned hard work to create the largest and fastest single fibre network across Africa," says Mr Rudnick.

"Traffic comes onto it from across Africa and from other continents. Access is not limited to just our direct business and retail customers. We sell capacity to other operators.

"I firmly believe that the small businesses of Africa need access to affordable broadband to grow. Fibre is key to the future economic prosperity of Africa."

Liquid Telecom chief executive Nic Rudnick believes internet connectivity is a human right

The company is working hard to increase its cable infrastructure

In the ether

However, not all believe that fibre is the right solution for Africa.

Alan Knott-Craig, founder of South Africa's Project Isizwe, believes wireless technologies are the way forward. He aims to bring free internet to everyone in South Africa by installing wi-fi hotspots in low-income areas across the country.

"Fibre is not the future for Africa. The distances are too big, the existing footprint too small. Wireless is the future," he says.

According to Mr Knott-Craig, satellite and microwave technologies will dominate African transmission networks in the future, while wi-fi and 3G will provide connectivity over that last mile to the home or office.

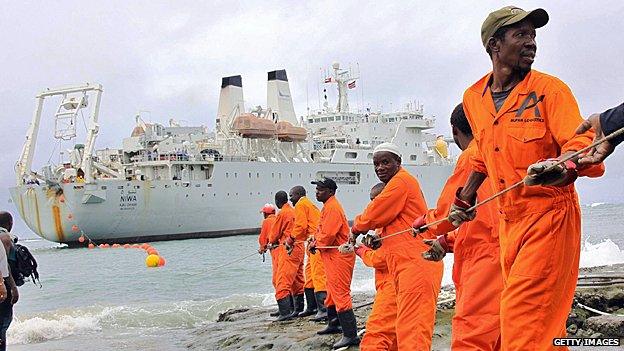

Workers haul part of a fibre optic cable onto the shore at the Kenyan port town of Mombasa in 2009

One reason for this, he believes, is that wi-fi is the most suitable form of connectivity for mobile devices - Africa's breakthrough technology - and as such, is the best way to achieve universal internet access.

"Wi-fi is the only economically feasible technology. Not only is it robust, but most families already have access to a wi-fi-enabled device," he says.

Satellite nation?

Not surprisingly, satellite connectivity provider, Gilat Satcom, agrees.

The company points to the fact that fibre laying in Africa has mostly been restricted to big cities. But World Bank data estimates that only 37% of Africa's population actually live in these urban areas.

Satellite is the therefore the most effective way to reach rural areas, and thus the majority of the population, Gilat believes.

"In the smaller cities, towns and rural areas, wireless broadband and satellite are still the only practical options," says Dan Zajicek, Gilat Satcom's chief executive.

Project Isizwe aims to bring free internet to all in South Africa by installing wi-fi hotspots in low-income areas

"Despite a few predictions that demand for satellite would start to drop away as the amount of operational fibre in Africa increased, the opposite has occurred," he says.

As demand for satellite connectivity is expected to take-off, providers such as Gilat are racing to improve their technologies so that costs can come down.

"We think that rural Africa will continue to depend on satellite capacity over the next few years," says Mr Zajicek.

"The good news for people and businesses in Africa is that we expect a significant fall in prices as a new generation of satellites are being launched to replace old satellites.

"Improvements in compression techniques used by the smart satellite providers will also reduce costs passed on to end-users."

A standard unlimited 1Mbps satellite package for a small business will start from $50 (£34) per month, says Gilat.

Join the dots

One thing everyone agrees on is that widespread internet access can have a profoundly positive effect, particularly on small businesses and in lower-income areas.

"The most immediate impact is making it easy to find jobs online and apply electronically," says Isizwe's Mr Knott-Craig.

"There are job seekers that have been recorded at 1am on a Monday morning searching for jobs," adds the projects chief operations officer, Zahir Khan.

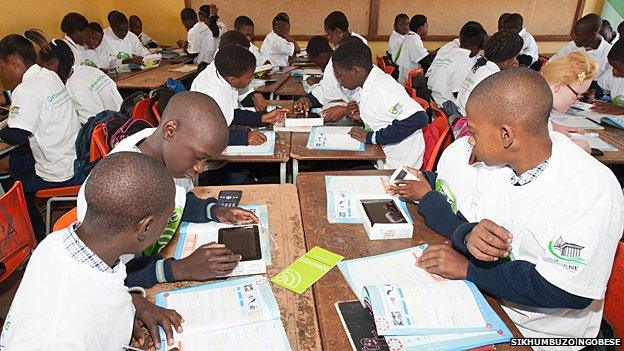

Mobile phones are one way to get rural communities online using 3G or 4G technology

"We have students and learners that are using the services daily for research to improve the quality of their assignments and report submissions," he says.

Another point of agreement is that the cost of internet must come down if this impact is to be felt.

"3G is virtually ubiquitous in Africa, provided you have money. If you are poor the internet is inaccessible because 3G data rates are simply too expensive. The need and the highest impact is in low income communities," Mr Knott-Craig says.

In the meantime, technology hubs remain a lifeline for small business in much of Africa.

"It's great to be able to provide fast internet in a continent that is still seen by many outsiders as being behind - and because of this, mobile and web businesses will be the future of Kenya's success, that, I'm sure," says Nairobi Garage's Hannah Clifford.

"It's really inspiring to see these changes happening."