Why 'secular stagnation' matters

- Published

- comments

Over the last few days I've been reading a blog debate between former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers, former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke and Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman.

My first thought is that we really do live in a golden age of macroeconomic commentary. This is the sort of argument that used to play out slowly in academic journals and behind closed doors in seminars, today though anyone with an interest can read along in real time.

The question at stake is the issue of "secular stagnation", which is probably the biggest and most important controversy in macroeconomics today. This is not though a debate for the ivory tower, it's an issue with significant real world implications.

Whilst I doubt we'll hear any politician utter the phrase "secular stagnation" in our own general election campaign, it is (beneath the surface) one of the issues at stake.

Labour and the Conservatives are fighting the election on the basis of very different public spending plans, the largest gap between the parties in a generation.

At least in part, differing views on secular stagnation provide theoretical underpinning for these positions. George Osborne rejects the notion, external while Ed Balls co-chaired a commission that took the idea very seriously. , external

Investment returns

So what is secular stagnation? It's an idea that originated in the late 1930s with the US Keynesian economist Alvin Hansen. He worried that growth was fundamentally slowing and emphasised demographic factors (such as slowing population growth) as a driver of this. He was quickly proved wrong, in part by the postwar baby boom.

Larry Summers revised and updated the hypothesis in late 2013. Since then a veritable who's who of prominent macroeconomists have weighed into the debate on both sides.

In a nutshell secular stagnation is an attempt to explain the weakness of the global recovery in advanced economies since the 2008 crisis.

The central idea is that something has happened to the economy which means that the interest rate required to generate enough investment to bring the economy to full employment is now negative in real terms (i.e. after adjusting for inflation).

When inflation is low - as it is now across the advanced economies - that means it is exceptionally hard for central banks to set interest rates low enough to generate full employment.

If inflation is 2%, then an interest rate of 1% equates to a -1% real rate. But if inflation is zero, then an interest rate of 1% is still positive in real terms.

This is the issue of the "zero lower bound", the fact that (until recently anyway) there was widespread believe that interest rates could not be cut below zero.

Simply put, the Summers thesis is that advanced economic growth over the last few decades has been increasingly reliant on a series of financial bubbles (whether in tech stocks or housing) to generate enough investment to achieve full employment.

Larry Summers argues that fiscal policy should be used to drive growth

For Summers, the logic of secular stagnation points to a more expansionary fiscal policy.

If monetary policy is less effective due to the zero lower bound and low inflation, then fiscal policy (especially more government spending on infrastructure) should play a bigger role in driving growth.

Summers has restated the theory in a recent blog post. , external

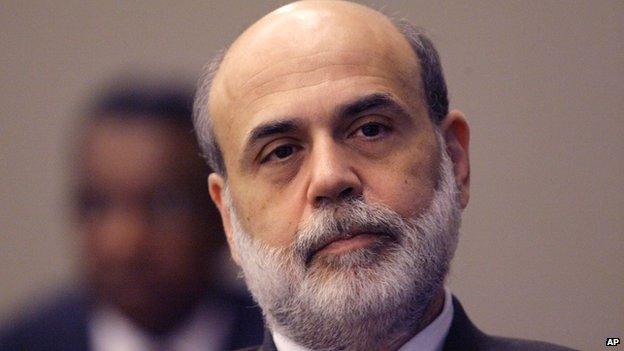

Ben Bernanke takes issue with the idea of secular stagnation., external His most important critique is that one has to consider the international dimension. He argues that if the rate of return on US investments was so low that investors would not be willing to investment without a negative real rate, they would seek higher returns abroad.

The availability of better investments abroad should help defeat secular stagnation at home.

As money flows out of the US that should weaken the dollar and help boost exports, which could help the economy get back to full employment. For Bernanke, secular stagnation in one country is unlikely to last.

'Weak euro' fear

He offers an alternative explanation for the macroeconomic history of recent decades, one focussed on international capital flows. It's a return to a previous theme of his own, the existence of a "global savings glut". , external

This the idea that, from the late 1990s until the late 2000s, there was a large excess of desired savings over desired investment in countries in East Asia and the oil producers in the Middle East.

These savings flowed to the US (and other advanced economies), pushing down interest rates and holding up the value of currencies such as the dollar. This led to large trade deficits in the US, as imports were cheap.

The observed behaviour of an economy suffering from secular stagnation or the impact of a global savings glut appear similar - low interest rates, low inflation and an inability get to full employment but the correct policy response is very different.

Under secular stagnation it is, as Summers argues, a fiscal expansion. But if the problem is a global savings glut then the right policy is to focus on what is driving the situation - i.e. over-saving abroad.

Ben Bernanke warns of a return to a 'global savings glut'

Bernanke argues that the big source of the previous glut was China but more recently it has been Germany.

Paul Krugman has now weighed into the debate., external He agrees with many of the broad points made by both Summers and Bernanke.

Krugman points to the experience of Japan in the 1990s and early 2000s as an example of how a country can find itself trapped in a state of secular stagnation even with international capital mobility. Despite interest rates being much lower in Japan than, say, the US the real interest rates in the two countries were very similar.

The existence of deflation (falling prices) in Japan had a big impact on the real rates of return available. As Krugman explains:

"The moral of the Japanese example is that if other countries are managing to achieve a moderately positive rate of inflation, but you have let yourself slip into deflation or even into 'lowflation', you can indeed manage to find yourself in secular stagnation even if the rest of the world offers positive-return investment opportunities."

Professor Krugman argues that the current global savings glut - driven by Germany - is likely to persist. Poor demographics are likely to lead to weak demand in Europe, a continuing excess of desired savings over investment and persistently weak euro.

Illusion of control

The problem for Krugman is that a secularly stagnating Europe is exporting much of that weakness abroad through a weak euro, which supports their own economy through boosting their exports but causes problems for producers overseas.

So whilst accepting much of Bernanke's analysis when it comes to policy, Krugman lines up with Summers. He thinks that if Europe's trade and investment balances are fundamentally about weak demand then the required response is boosting demand through fiscal policy.

So, who is right? Summers, Bernanke or Krugman?

All three make compelling cases and there are no doubt important elements of truth in all three cases. What we can say at this point, is that when three of the world's most distinguished economists disagree, it's worth paying attention to the debate.

I would add three observations.

The first is that Professor Krugman may (and it's just a "may" at this point) be too pessimistic on Europe. It sometimes feels like too many obituaries have been written on eurozone growth.

Paul Krugman believes that the eurozone is a source of secular stagnation

The second is that the debate between the three so far has focussed mainly on the demand side of the economy.

If we are trying to explain a historically weak global recovery it may be that neither secular stagnation nor a global savings glut offers the full story.

Certainly in the case of the UK, productivity growth (the ultimate driver of higher living standards) has been exceptionally weak. And even if the UK is an exceptional case, productivity weakness has been widespread globally - as Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee member Martin Weale has recently argued. , external

As Karl Whelan has argued,, external there are reasons to worry that this reflects a longer term trend rather than just a hang-over from the financial crisis.

In other words, if we are trying to explain weak growth we may need to pay as much attention to the supply side of the economy as the demand side. In fairness to Professor Summers, his broader secular stagnation thesis does take into account supply side factors which have reduced the desired rate of investment.

My final observation is one that is especially relevant during a general election campaign - that, to quite a large extent, the political debate on the economy suffers from an illusion of control.

Whether one listens to Krugman, Bernanke or Summers there are powerful global forces at work. Flows of capital and the state of world demand have a large impact on the size of the government's deficit, the level of interest rates and the economy's rate of growth.

In much of the British political debate most of these outcomes are assumed to be under UK policy makers' control.

I don't mean that be taking fatalistically or to imply that political choices don't matter for the economy - they very much do. But they aren't the only factor at work.