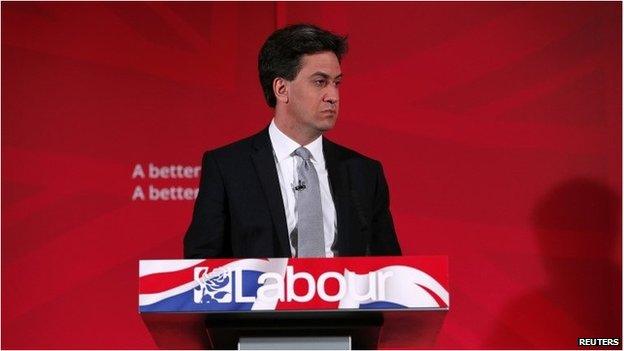

Miliband as Thatcher not Foot?

- Published

- comments

The last rites have been read over New Labour, as opposed to Miliband-brand Labour, quite a few times over the past few years.

But yesterday's announcement by Ed Miliband that as prime minister he would abolish non-dom status may well be the last nail in the coffin of a political approach - not quite an ideology - which had at its core the idea that it was better to get the wealthy and powerful in the tent, rather than doing what they typically do if they are outside the tent.

To understand the scale of the shift, I spoke to a New Labour veteran. This is what he said to me about the non-dom cull: it would "alienate some people whose goodwill is a good investment for us, send the wrong signal about the UK and [is] a rather useless piece of posturing (as the last Labour government concluded for 13 years)".

Symbolic break

In other words, it is a powerful and important symbolic break with the Blair era. But Ed Miliband would say the policy is about a good deal more than gesturing. At its kernel, for him, is a big change in his assessment of how to fulfil Labour's mission of helping the poorest.

Tony Blair's view was that reaching an accommodation with the wealthiest and most powerful was not only the route to electoral success, but was also the best way of stimulating economic growth that would generate the tax revenues that could then be deployed to lift up the poorest.

Until the great crash and recession of 2008, he and his successor Gordon Brown could argue that their calibration of Labour's style of left-wing politics, as friendly to the City of London and to those accumulating vast fortunes here, had helped to generate prosperity which in turn could be used to fund a massive expansion of spending on schools and hospitals - and therefore went with the grain of Labour history.

But for Miliband, that calculation has had to be re-done, as living standards were savagely squeezed in the years after that profound economic shock, and the welfare state has been rolled back.

No more wooing

Miliband would also say that the stagnating gap between the incomes of rich and poor and the widening wealth gap have shown that collaborating with the wealthy has not delivered adequate fruits to the poorest.

That's why he decided that he no longer had to woo them with non-dom tax breaks, and it also explains an industrial policy - that includes breaking up the banks and freezing energy prices - which is more overtly challenging of the status quo than was typical of New Labour.

Now the conventional view from the centre of politics of what he's doing is that he is a throwback to Labour's left-wing past, a Michael Foot in a sharp tailored suit.

But that doesn't feel right to me. He isn't resorting to the traditional left-wing solutions of nationalisation, significantly increased state spending, incestuous deals with trade unions or penal increases in tax rates.

What he is attempting to do - perhaps naively, perhaps clumsily - is encourage competition, give more power to consumers, nudge up the minimum wage and take on vested interests.

Change of course

I am not sure whether it is being kind or cruel to him to say that his repositioning of Labour - conspicuously to the left, but not by the normal route - should be seen not like Foot but more like Margaret Thatcher: like him, she upset the grandees in her party who believed that political and economic success could only be won from the conventional centre ground.

And the backlash from the establishment against Miliband is not unlike the way - for example - that the vast majority of economists in Britain ganged up more than three decades ago to argue that her hairshirt economic policy and economic liberalism was bound to fail.

Thatcher correctly identified that a particular economic model - of the state wagging the economic dog - had run its course after three decades. Miliband has made an equally bold judgement (which may or may not be correct) - that the prevailing economic model of the 35 years since then, that of a relatively unfettered private sector wagging the economic dog - has also run its course.

Hostility

It is interesting, in this context, that in opposition Margaret Thatcher was less popular than the then prime minister, "Sunny" Jim Callaghan, that her personal rating (like Miliband's) lagged her party's, that she offended large parts of the media, and that many people thought her appearance and style of speaking were a bit weird (sound familiar?).

What is also important about Ed Miliband is that he appears to have more-or-less given up on reaching an accommodation with what would be seen as the right-wing media. In a total departure from the convictions of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown he seems to believe that he can win in the face of extreme hostility from the country's best-selling newspapers.

He is presumably gambling that Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and the rest have disintermediated "old" media to an extent, that social media gives him the ability to go over or under the papers when talking to voters.

And he is also counting on Labour's greater number of constituency volunteers to outgun the Tories' more ample financial resources (and the party's private polls indicate it may be winning the war on the ground).

So what is striking, as the election looms, is the sheer scale of Miliband's repositioning of Labour, both in respect of fundamental policy and the communication of policy - and it is also striking that this has not led to the scale of meltdown in Labour's popularity that New Labour's vanguard would have predicted.