Deflation: What it means in practice

- Published

When inflation was last negative: a Glasgow flat in 1960

In March 1960 Eisenhower was in the White House, Macmillan was in Downing Street, and Cliff Richard and Perry Como were in the Top 10 of the pop charts.

It was also the last time that the UK had negative inflation, according to the Consumer Prices Index (CPI).

In fact back then inflation had been negative for three months running, and in March 1960 reached its biggest fall, at - 0.6%.

Not since then have we known the spectre of deflation.

At first sight, it looks like pretty good news.

Essentials like petrol, food and transport are cheaper than they were a year ago.

Yet for those who produce the oil, or the farmers who make the milk, this is not good news at all.

But first, does a decline of -0.1% in CPI really count as deflation?

Harold Macmillan was Prime Minister when inflation was last negative

Is this really deflation?

Sorry to be pedantic but, so far, this looks like more of a case of "negative inflation", not deflation. The only difference being that economists define negative inflation as something short-term, while deflation is longer-term. Anyone going to a Japanese take-away in Tokyo, where prices have stayed the same for two decades, knows the difference between the two.

And that is why the governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, said the UK economy was likely to go into negative inflation "briefly." At last week's quarterly inflation report, he said: "A temporary period of falling prices should not be mistaken for a damaging spiral of deflation." You have been told.

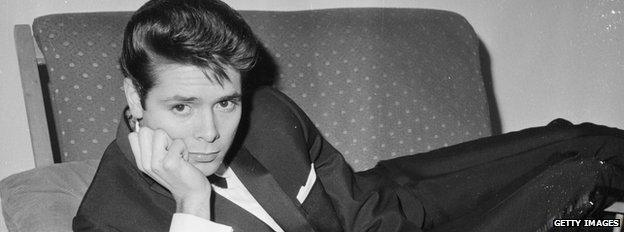

Cliff Richard was in the charts in March 1960

Is negative inflation a good thing?

In this particular case, Mark Carney said negative inflation was "unambiguously good". That is because lower petrol and food prices are good for everyone. Even the farmer gets some benefit, because he too buys food and fuel.

If we spend less on filling up our tanks and doing the supermarket shop, we have money to spend on other things. On average, we're each expected to save £140 as a result of lower petrol prices this year. So businesses from fashion stores to fun-fairs should benefit. But if negative inflation is unambiguously good in this case, when is it ambiguously good - or unambiguously bad?

When is negative inflation bad?

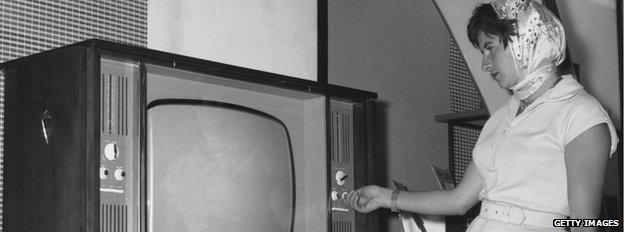

Food and fuel are things we all need to buy immediately. But other goods - like televisions or cars - are discretionary. If the price starts to go down for any sustained period, we could save money by buying them later. If we delay our spending, which amounts to around 70% of all economic activity, the economy will slow.

The economist Roger Bootle divides negative inflation into good and bad: 'Bad' is when there is such weak demand in the economy that companies are forced to reduce prices - and wages. 'Good' is when negative inflation comes from lower import costs, as is the case right now.

What is the impact on debt?

Negative inflation and even more, deflation, is not good news if you are a borrower. Imagine you take out a mortgage, and your fixed monthly repayment is £500. In an era of deflation, your wages might even go down. In which case, your £500 becomes a larger proportion of your salary - and paying it off becomes more painful.

In an era of high inflation the opposite is true: as your salary rises, your borrowing becomes a smaller proportion of your spending, and so becomes more manageable.

It's not just people affected by this. Governments with large deficits experience exactly the same thing- and thus long for some inflation.

Does deflation affect wages?

In a time of rising prices, it is easy for companies to put up wages. But it is also easier for them to give below-inflation pay rises. If inflation is 3%, a pay rise of 2.5% still feels like a pay rise. But if inflation is zero, or negative, it is hard to cut salaries.

Doing so may be necessary, but it is bad for morale and productivity.

Will deflation affect interest rates?

Yes. The longer that inflation is below the Bank of England's target, the longer it will be before a rise in interest rates. But more than that, the longer we have zero or negative inflation, the more likely it is that the next move in interest rates could be down, rather than up.

But negative inflation is unlikely to last. Mark Carney has said CPI should pick up "notably" towards the end of the year. As a result of that, experts still expect that interest rates will rise in the summer of 2016.

Does deflation mean negative returns on index-linked savings certificates?

No. The return - or interest rate - on Index-linked national savings certificates is based on the Retail Prices Index (RPI) measure of inflation, not CPI. RPI, which includes some housing costs, is currently + 0.9%.

But even if RPI went negative, the return on index-linked certificates would not fall below zero. You would not be paying the government to lend it money.

National Savings and Investments (NS&I) adjusts the returns on such products throughout the year, to take account of ups and downs in RPI.

Similarly, pensions linked to inflation are unlikely to be affected.

Many private sector defined benefit schemes are linked to RPI, while most public sector schemes use September's inflation rate to set annual pension pay-outs.