How SNP tests Labour's economic credibility

- Published

- comments

Earlier this week, Deutsche Bank said there were few positive outcomes for financial markets from the general election, based on what polls are saying.

It thought the most likely of its two so-called "good" outcomes was a Labour-led government supported by the SNP and the Liberal Democrats. This it saw as leading to increased taxes, less austerity and a slower reduction in the deficit.

The consequence would be "higher near term growth thanks to stronger government spending" - which would encourage the Bank of England to put up interest rates earlier than would otherwise be the case.

That may not be the kind of scenario to lead to the Krug being cracked open in the City, but Deutsche then asked, "will this be seen by the markets as any worse than the possible consequence of a Conservative led government?".

It said that the promise of an EU referendum by 2017 - "assuming the Conservatives can convince their governmental partners to include this in a coalition agreement" - could "have negative consequences for both investment and sterling", because there would be "two years of uncertainty over whether the UK remains in the single market".

It pointed out that Britain is the "second most important destination in the world for inward investment", due to membership of the single market. So there would be "a serious test of the resilience of foreign direct investment and [this] would likely depress the currency as a result".

Or to put it another way, Deutsche is saying that markets are unsettled because both major parties have been or would be held hostage by populist nationalist parties - UKIP for the Tories, and the SNP for Labour.

But one important difference between Labour and the Tories is that arguably UKIP has already wagged the Tory dog, because David Cameron offered the EU vote demanded by Nigel Farage's party. That is largely done and dusted.

The more pressing problem for Labour is that its position on how to deal with the surge in popularity of the SNP is not settled - which allows the perception to grow that the SNP would end up wagging the Labour dog when in government, though in an unspecified way.

And that uncertainty is damaging to Labour's political and economic credibility.

There was a manifestation of this messiness on Tuesday, when Labour's leader in Scotland Jim Murphy said that "Ed [Miliband] was really clear at the UK manifesto launch today, it's only Labour that will end austerity" - which was very different in tone from the insistence of the shadow Chancellor Ed Balls that there would be "cuts" under a Labour government.

The nightmare for Labour is that at least part of the cause of the extraordinary surge in the popularity of the SNP - to more than 50% of the vote in a poll earlier this week - is that it is campaigning on a platform of pushing up public spending.

So Jim Murphy feels he can't say that the austerity would roll on under Labour. But this is precisely what Ed Balls and Ed Miliband feel they have to imply in England - they have to say that there would be cuts in "non-protected" departments (everywhere but schools, health and overseas aid) - if they are to be given a hearing on their claim to be serious in restoring the public finances to a more sustainable condition.

What is more they have raised their credibility stakes in this respect by saying, on page one of their manifesto, that they "will not compromise" on their so-called "budget responsibility lock" to reduce debt and deficit.

They could, of course, theoretically argue that Scotland would be treated more kindly in budgetary terms than England, that its block grant under the Barnett formula won't be adjusted in the normal way to take account of budget spending decisions. But that would be a more-or-less guaranteed vote loser in much of England. Why should there be a special Scottish key that unpicks their fiscal lock?

So it is a dreadful problem for them.

There is a plausible and extreme way through it for them. Labour could say that a vote for the SNP is a vote for Scottish independence - and then to flag up the analysis of the Institute for Fiscal Studies which shows that Scotland's deficit between spending and taxes as an independent nation is so much worse than the UK's, at a forecast 8.6% this year versus 4% respectively.

But that has flaws (ahem).

One is that the more that Labour shouts about Scotland's deficit, the more it signals to England that spending on public services in Scotland is £12,735 per head compared with £11,435 for the UK as a whole - and the more, therefore, it risks fracturing support for the union south of the border.

But the more important (and obvious) flaw is that a vote in a general election is simply not a vote for independence.

Which means that somehow Labour has to imply that a vote for the SNP is in effect a vote for a Tory government, even though the SNP's leader Nicola Sturgeon says she would never support a Tory-led government.

And if Labour were to succeed with that message, Labour then has to plausibly argue that a Tory-led government would make cuts to Scotland's block grant from Westminster under the current devolved system, or would abandon its unionism and would usher Scotland towards separation from the UK on unfavourable economic terms.

In other words, Scotland is a bit of knotty problem for Labour.

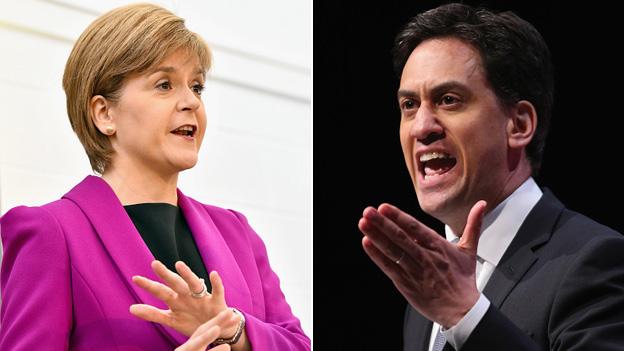

Which is why tomorrow's leaders' debate, sans David Cameron, could turn out to be more gripping than the first one which included the prime minister, because the outcome of the election, and indeed the future of the UK, could be decided by the head-to-head battle between Ed Miliband and Nicola Sturgeon.

It may not be an exaggeration to say that this is Miliband's toughest-ever political test - how to shore up Labour's vote by taking on Nicola Sturgeon without appearing to be the posh boy from London lecturing the Scots on what's best for them.