Giving everyone in the world an address

- Published

The spot marked on the map in south west Egypt has the address polygons.amuse.nets

"Where the streets have no name," sang rock frontman Bono on one of U2's biggest hits.

"It must be hell being a postman, then," came the sarcastic rejoinder from the music press.

But out in the real world, about four billion people on the planet actually live in places that have no street names, no house numbers - in fact, nothing that constitutes a proper address.

And without that, they're off the map. They can't get a bank loan, they can't run a business, they have no voting rights or access to public utility services.

And, in fact, they have no postmen.

"Most of Africa, Asia and South America have this problem," says Chris Sheldrick, 33, founder and chief executive of what3words, a small UK-based company that has come up with a radical new approach to the addressing system.

"Trying to do a census with addresses like 'fourth lamp-post down the road' is really very inefficient, and we're coming in to say, 'No, you can do this differently'."

New code

In the past, countries without a proper set of addresses have tried to change facts on the ground by mapping out the area, and copying the developed world's way of doing things, such as adding street names and numbers.

However, as Mr Sheldrick says, that can take a decade: "Places like Ghana have tried that unsuccessfully. Some properties have five different addresses stamped on them."

Of course, existing co-ordinates of latitude and longitude, and the Global Positioning System used by sat-nav technology, already provide a way of pinning down any location in the world.

Chris Sheldrick's company was born out of his frustration with conventional addresses

"But errors creep in very quickly and it's just not human-friendly," says Mr Sheldrick. "We had to convert them into a new code, something where a human being would say 'that's really easy'."

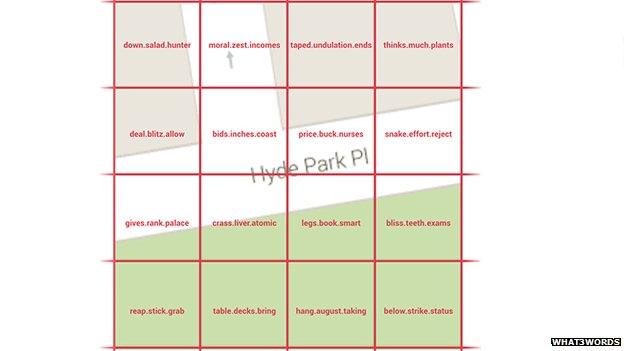

What he did was to divide the world up into 3m-by-3m squares, and assign each a unique combination of three words.

He says: "With 40,000 dictionary words, you have 64 trillion combinations, and there are 57 trillion squares."

Mr Sheldrick's own headquarters in west London has the address index.home.raft, while this article was written at speaks.nests.loans.

Admittedly, most people have still to embrace this idea and apply it in their everyday lives.

But in places where people have no other viable way of identifying where they live, it is likely to prove a useful way of getting on the local authorities' radar, especially as internet-based services pick up on it and build it into their systems.

Favela boost

The service is free to use for consumers and can be downloaded in app form, but companies pay to license the technology and incorporate it into their own products.

"We've got about 25 apps and services who've done that so far," says Mr Sheldrick.

Interestingly, he says what3words has not had to market itself intensively, because news about his product has spread by word of mouth.

"We've had people coming to us," he says. "It's not often that the idea of what an address is has been challenged. People become advocates and spread the word quite aggressively."

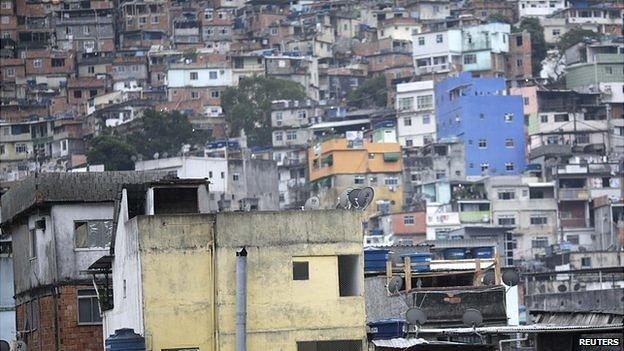

In some parts of the world, the idea is already bearing fruit. The Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro contains the largest shanty town or favela in the country - the district of Rocinha, home to about 70,000 people.

Rocinha is not exactly a shining example of urban planning

Because of the haphazard way in which the area originally developed, its sprawling maze of lanes and alleys has never been subject to a proper system of addresses.

But a local company, Grupo Carteiro Amigo (or in English, Friendly Postman Group), has found ways of overcoming that handicap.

Founded in the year 2000, the firm says its aim is "to give residents back one of their basic rights" - that is, to have things sent to them by post.

The Brazilian postal system has no obligation to provide a full service in the area, so Carteiro Amigo set up its own system. Now 4,000 families in the favela pay 18 reais (£4; $6) a month to have letters and parcels delivered to them.

A what3words diagram of a small corner of London

Local businessman Carlos Pedra da Silva says he got the idea for the company when he was employed as a census worker, gathering data on the favela's inhabitants.

Realising that many of them didn't know their addresses, he asked them if they would pay to receive post at home. "The responses were almost 100% positive," he said.

When he found out about what3words, he realised it suited Carteiro Amigo's needs perfectly and joined forces with Mr Sheldrick, setting up a pilot project to spread the address system through the favela.

Mr Sheldrick sees the Rocinha scheme as a perfect example of how what3words' address system can make a difference.

"People there are saying, 'I want to get my shoes delivered the same way someone else can get their shoes delivered'," he adds.

Multilingual system

Naturally, in order to reach the Brazilian market, what3words has had to devise three-word addresses in Portuguese as well as English.

In fact, the system is now available in eight languages, including French, Spanish, Russian, German, Turkish and Swedish.

What3words' technology would more easily enable delivery firms to find any spot in Africa

What3words is currently working on versions in Italian, Greek, Arabic and Swahili.

Mr Sheldrick now employs eight people full-time, but brings in language experts on a short-term basis when needed to set up a new database of words.

And he has other languages in his sights.

"Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world, but it has no semblance of an address system," he says.

Mr Sheldrick, who came up with the idea after becoming frustrated with sat nav systems, also envisions a range of uses for what3words addresses.

"You can use them for something else other than delivery. People can say, 'I'll meet you there', and quote the address.

"It's a way of life where you can use your three-word address just as you can use any other address."