Financial crises: The devastating fallout

- Published

We're used to thinking about financial crises in numbers.

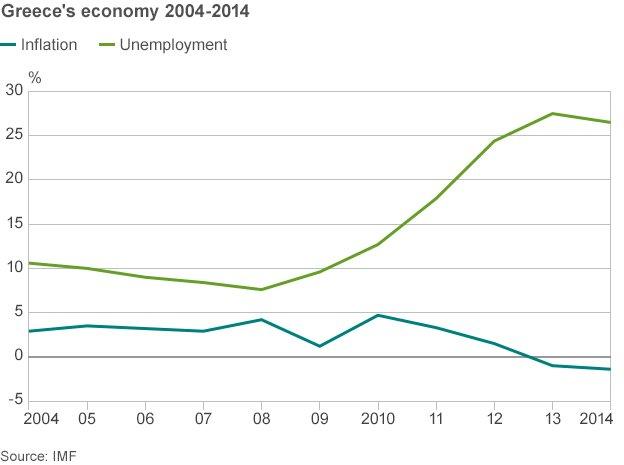

Take Greece. The embattled country's economy has shrunk by 25% since 2008, youth unemployment stands at 50%, while total debts are pushing €323bn (£234bn).

Enlightening as these numbers are, they tell you little about the extreme hardships suffered by many living in the country.

And it's not just casual onlookers that can become detached.

As Prof Simon Johnson from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), says: "When economic policymakers get together, it gets very abstract and the human dimension can be forgotten."

But the human consequences of financial crises are very real. Some are obvious - people lose their jobs and therefore their income, they can lose their home, watch their money become worthless in the face of rampant inflation or see their life savings wiped out.

Others are less so. "There are a number of health issues, primarily stemming from stress, a feeling of not being in control of your life and feeling powerless [to influence events around you]," says Prof Johnson.

"This affects people's health in a number of ways, such as excessive drinking, and can lead to a fall in life expectancy."

Indeed studies have shown an increase in suicide rates, in alcohol-related deaths and in mental health issues in countries hit by economic crises.

And the people who are hit hardest are invariably the poor.

"Better educated, [richer] people are more able to cope - they may see a fall in their paper wealth, but their prospects remain largely unchanged. The poor find it much harder to find a new job - they get hit really hard," says Prof Johnson.

"Inequality is compounded by financial crises."

Here, we speak to three people whose lives have been turned upside down by various financial crises across the world.

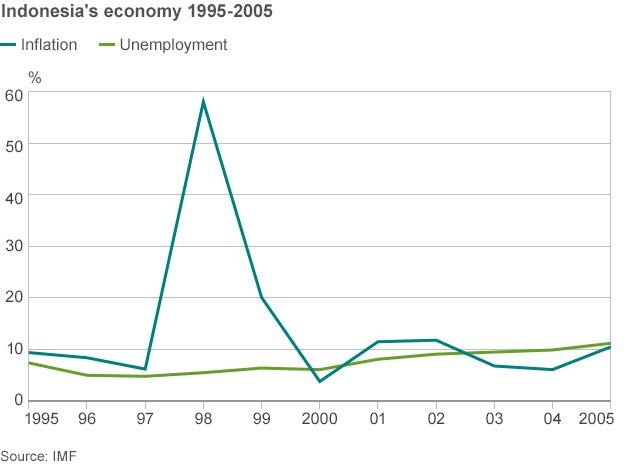

Indonesia 1997-1999

The wider Asian financial crisis started in Thailand.

The devaluation of the Thai baht in July sparked a chain of devaluations across South East Asia. Indonesia was one of the worst affected countries, and was forced to ask the IMF and World Bank for help after the rupiah quickly fell to an all-time low.

At the peak of the crisis, prices for basic foods shot up by as much as 80%, with Indonesians, fearing food shortages, clearing store shelves of staple goods. The crisis sparked nationwide protests that forced President Suharto to resign after 32 years in power.

Purnomo is 54 years old. He is from the city of Yogyakarta in Java, but lives and works in Utan Kayu, East Jakarta, selling chicken noodle soup by the roadside. He remembers the crisis all too well.

"About two years before before the economic crisis, I decided to set up a chicken noodle soup street stall.

"I was working at a batik textile factory at the time, and I wanted to increase my income so that I could pay for my two children's education. It was going well and we were making money. Chicken noodle soup is relatively easy to make and there was a demand for it.

"But when the Asian economic crisis started to hit Indonesia, it became very hard to keep our little store open. The price of everything went up dramatically. The price of wheat that made our noodles soared. Back then we used kerosene instead of gas for our stove and the price of kerosene became too much for us.

"It was frightening because as one of the 'little people' I didn't understand what was happening. I was forced to close down the stall.

"I felt incredibly vulnerable during the crisis because I didn't have an education. The powerful people were making decisions that we weren't part of. We saved money by eating very simple and cheap food at home. We never ate meat during those years.

"It wasn't until the presidency of Suslio Bambang Yudhoyono in 2004 that the Indonesian economy started to recover and I decided to quit my day job and open my roadside chicken noodle soup stall again.

"The thing that I am most proud of is that even during the hard years of the economic crisis I was still able to keep my two children in school. I said to them the most important thing is your education. Both my children have graduated from university now. My daughter is a French language teacher at an international school and my son works in aviation. I am very proud of them."

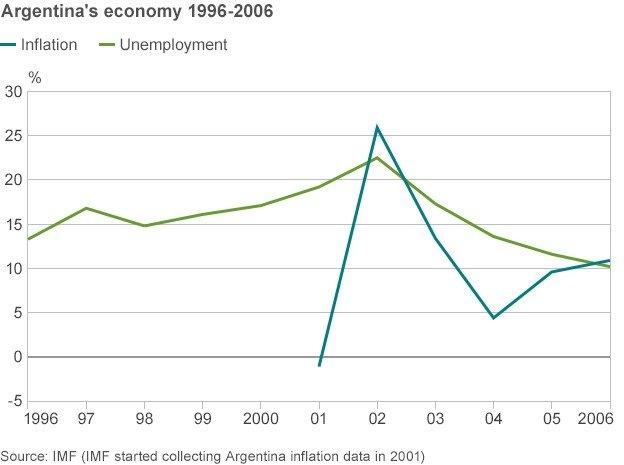

Argentina 1998-2002

Argentina is a country with a turbulent history of economic crises. The 1998-2002 period was one of the hardest in its history, the economy shrank by almost 30%. At that time, bank deposits were frozen, the country defaulted on its debts and Argentina's currency, the peso, depreciated dramatically against the US dollar. All sectors of society were affected.

Jose Juan Fernandez Reguera is 66 and is president of Losada, a publishing house founded in 1938.

"With humour, I can say that we are the kings of the financial crisis in Argentina, because we passed through all kinds of money problems, but finally stayed afloat."

He will never forget the 1998 crisis.

"In just a few short months, sales of books fell sharply, the price of inputs tripled and importing books became very expensive.

"With the Argentine peso you could buy a US dollar. All of a sudden, you needed three to four pesos to buy a dollar, and this in a country where the dollar still rules.

"The 'corralito' [freezing bank accounts and forcing those with dollars to convert their accounts into devalued pesos] was terrible. There was an economic crisis, but also a mental one, as a consequence. The mood of the people was on the floor.

"The situation made me very sad. In front of my library there are two banks, and it was heartbreaking to see the despair of people taking out their savings.

"Equally the uncertainty of not knowing what would happen to my business was very difficult to cope with. I tried to hide the situation from my employees but it was hard, really hard."

"Argentines did not trust the banks and we had no access to credit - the crisis greatly affected my business."

The revival of the economy five years after the crisis began, together with the reading culture of the Argentines, meant the book industry finally recovered.

In fact, Mr Fernandez Reguera has just bought a new publishing house called Aique.

"With subsidies and other measures, the government sent money to the street. People increased their standard of living and consumption.

"I remain confident in this country and I believe that behind every crisis there is an opportunity. When everyone takes two steps back, I take one forward."

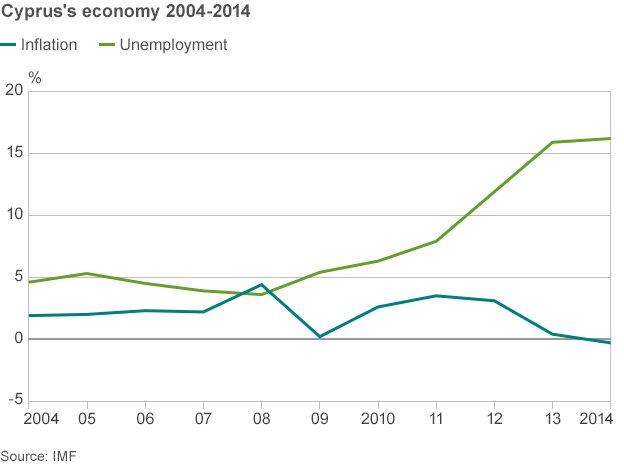

Cyprus 2012 -

An overblown government sector and a stubborn refusal to reform, together with overexposed and mismanaged banks, led to Cyprus asking international lenders for financial assistance in early 2013. The EU, European Central Bank and IMF agreed to a €10bn (£7bn; $11bn) bail-out package but set strict conditions, including a one-off 48% levy on deposits over €100,000 held at the country's two biggest banks.

Pambos Charalambous, a 39-year old prison guard, and his 36-year old wife Helena were struggling to get their life in order at a time everything around them was collapsing. They got married in 2012 and, like many newlyweds, immediately set out to buy a place of their own.

With a combined income of €3,000 a month and state housing aid on the way, the couple was looking at a bright future. They bought a three-bedroom house in the outskirts of the capital Nicosia for €166,000 and started paying off the loan.

Everything changed in late 2013, when the government went into full austerity mode.

"We didn't know what was going to happen. How could we have known? We were not economists. The government didn't even know," says Pambos.

Following the deposit levy, struggling banks imposed far stricter conditions on housing loans, and soon enough the property market plummeted.

Economic growth went into reverse and many businesses had to cut back on staff and slash salaries to make up for huge loses in revenue. One of the victims was Helena, who lost her job, while Pambos saw his salary reduced by almost a third.

Soon welfare benefits also fell victim to austerity, including the housing aid upon which the couple was counting and was assured they would receive. Stricter lending criteria were then imposed, adding in a stroke €70,000 to newlyweds' debts.

"You feel helpless, angry, trapped," says Pambos. "I mean, it wasn't our fault the economy crashed. We weren't in this situation because we were lazy. We were in this mess because the fat cats wanted to line their pockets, no matter who they trampled on."

In the space of one year, Pambos found himself with a €162,000 bank debt instead of the €100,000 he had planned for, and with less than half the money coming in to service it.

"When I stopped paying, the bank notices came pouring in but there was nothing I could do. It's either pay daily expenses or service the loan and starve."

They have tried to sell the house but in the past two years have received not a single offer.

Unable to cope, Pambos made headlines recently when he announced on Facebook he was raffling off his home. Authorities soon put a stop to it and now he is working with a lawyer to find a way to press ahead with the sale.

"If I can't do this, we are done for. I will lose my house, thrown out in the streets and still have to pay the bank. This is my last chance".