Why Clarks is measuring feet with iPads

- Published

WATCH The story of the iPad device and how the data is gathered at Clarks' headquarters

If you go to a shoe shop during half term next week, you may see lots of children getting their feet measured with iPads. Shoe company Clarks has bet millions on the scheme, hoping it will be rewarded with an invaluable bonanza of digital data.

Getting children to focus on getting their feet measured for shoes is one of life's more trying activities. Shoe shops at school holidays and half terms are hardly havens of tranquillity, as many parents will testify.

For today's tech savvy kids, would putting an iPad into the mix make the whole experience more palatable?

The idea came to Chris Towns, innovation manager at Clarks, as he was driving in his car five years ago, mulling over the potential of the iPad, which Apple had just launched.

He immediately set to work on his vision, enlisting the help of a product design team and an app developer. Last year Clarks rolled out its patented foot measuring system, which harnesses the iPad (though the technology could work on any tablet in theory).

You can see how the device works in the video here:

Peter Rickett of Designworks demonstrates the iPad foot gauge that he and his team developed

In essence, it combines the mechanism of a traditional plastic foot gauge with the tablet computer. A plastic bar touches the tip of the toes, but the precise measurement is recorded by the tablet's touchscreen, rather than the human eye.

The team has also developed a new kind of digital tape measure as part of the system. The Digitape looks like a plastic claw, and measures the width of the foot by gently clamping around it, before communicating the data by bluetooth to the iPad.

The child is enticed through the whole procedure by animated cartoon characters, who hop around telling the youngster what to do next.

Appropriate measures?

The iPad foot measuring system has won several industry awards. These have cited the device's success at holding a child's attention.

The first portable digital foot measuring device of its kind, it certainly stands out from its predecessors, and appears user-friendly.

Electronic foot gauges of the past were large, cumbersome and prone to break.

Clarks electronic foot measuring devices from 1967, 1996, 2000 and 2006

But is this new method actually better for measuring feet?

According to Clarks, the new method will give more precise measurements.

"If you imagine the pixellation on the screen of the iPad, it's far more accurate than anyone trying to read a tape measure," says Mr. Towns.

Laura West of the Society of Shoe Fitters adds a note of caution though.

Although she applauds Clarks' initiative, she warns against relying too much on technology.

A shoe fitting fluoroscope from 1920 and a manual, mechanical foot gauge

"You can't necessarily say it offers an improvement, because measuring feet is not the same as fitting feet."

It takes the human eye to notice things like low ankle bone, high instep, pronation (the inward roll of the foot while walking or running), she explains.

"There is nothing better than a professional, qualified shoe fitter, and a handheld gauge is all that they require."

"The major benefit [of this device] is that it has the ability to store size information which will help Clarks plan ranges."

Body data

Indeed, it is the ability to store, and quickly send, information about our feet, that has motivated Clarks to invest millions of pounds in fitting out its stores globally with iPads and wifi. They are investing in the infrastructure necessary to harvest data.

"It's important that we are ahead of the curve," explains Chris Towns, surrounded by a sea of shoe prototypes at his desk in Clarks HQ, in Street, Somerset.

At Clarks headquarters in Street, Somerset, old fashioned shoemakers work alongside colleagues with 3D printing machines

"Body data, anthropometric data, to be able to own that and share it, clearly is the way forward."

Now every time a child's foot is measured with the device, be it in a Clarks store in the Bahamas, or China, the anonymous data is fed back live to Clarks's HQ in Somerset, feeding a growing database, for shoe specialists to scrutinize.

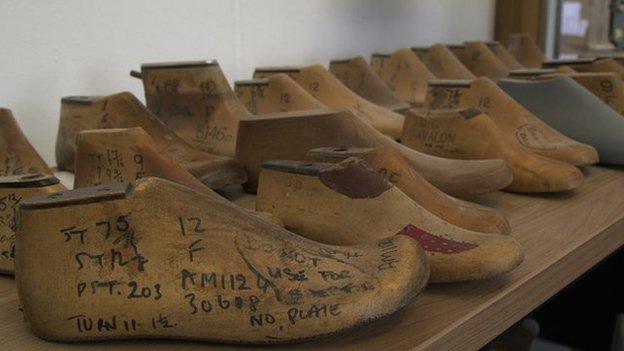

The HQ is a converted factory building - a factory that used to house Clarks's shoe manufacturing operation, which has since moved to China. The building now houses a vast research and development facility. Here traditional shoemakers carve wooden models, alongside colleagues using 3D printers. Upstairs, armies of smartly turned out buyers examine endless rows of shoes to second guess the next season's fashions.

Tucked away in the corner of this warehouse sits Scott Godley, a project manager closely involved in the iPad project. On his desktop computer a spreadsheet spools out the latest batch of global foot data coming in from the army of iPads.

He recalls the older, simpler method of collecting data - used until last year.

"Periodically, maybe every ten years, we'd do a foot survey."

This involved sending a man in a van, a foot specialist, driving around schools and shoe shops in the UK, taking a random sample of foot sizes.

An animated character guides the child through the measuring process

"Now it's [data] from thousands of children, whereas it was hundreds of children in the old days."

But what use is all this data to Clarks, why invest in collecting it?

From a business point of view it allows for better stock control, says Mr. Godley. Especially in new markets like China where the company doesn't know a great deal about the country's foot size characteristics, he explains.

"We can collect global feet measurement trends of all children and growth patterns," says Mr. Godley, "and we can build that into our product development."

But are our feet really that different according to where we live, and do average sizes for age groups really change much over time? Is there a business case for investing in this data collection enterprise?

UK footprint

It is already well known that in the UK, there are geographic patterns to foot size.

"There is a known factor in the industry that the Celtic foot is broader than the rest of the UK, for example," explains Laura West.

The "Celtic foot" is a very long term trend, but short-term changes could also affect foot size, making this market sensitive data for a shoe firm.

"Feet size is very much linked to obesity," explains West, "and we see children wanting wider and wider footwear."

Matthew Fitzpatrick, Dean at the College of Podiatry, agrees this could be something the data would reveal.

"Increased weight puts more strain on the foot," he explains. "Especially so with the soft tissue of a child's developing feet."

Predicting the best fits for the mass production of shoes has a long history

The data could show that obesity levels correlate with feet measurements, on a regional basis in the UK, and of course, elsewhere.

"We've seen adult foot sizes increasing by on average two sizes, both male and female, in the last 30 years, so it could be Clarks are trying to track this," adds Mr. Fitzpatrick.

The Clarks team is reluctant to discuss its data findings in detail, but it confirms historic results show there is a connection between health and foot size.

"A person's lifestyle and their diet will affect their body and foot growth, and will affect the width and length of each person's foot," says Mr. Godley. "The variations of lifestyle and diet throughout the UK changes quite considerably."

Global footprint

When told about Clark's data set, podiatrist Matthew Fitzpatrick's first response was naked jealousy.

"That's a goldmine of information," he marvels.

"We just don't have access to those sheer numbers. The people who come to us have foot problems, so don't make for a good, representative sample."

Clarks may well be collecting an unparalleled collection of rich "body data".

It may be fascinating to those whose day job is studying feet, but it remains to be seen if it is a worthwhile business investment.

Manufacturing around 50 million shoes each year, the business goal is to design shoe ranges that approximate in size to the greatest number of people's feet. Hence the premium put on accurate, up to date data.

In an age where all aspects of our lives seem to be going digital and online, it's also another example of a very simple activity - getting your children's feet measured in a shoe shop - being turned into a profitable exercise in data collection.