Interest rates would be higher without immigrants

- Published

- comments

There seems to be a bit of confusion about what the Bank of England and its governor said about the economic impact of migration.

First things first.

As long ago as last October, the Bank's chief economist, Andy Haldane, acknowledged that immigration depresses pay.

He noted that one respected study, by Dustmann, Frattini and Preston, found that each 1% increase in the share of migrants in the working age population leads to a 0.6% decline in the wages of the 5% lowest paid workers.

And to be clear, the general point that an influx of workers from abroad represents a weight on the pay of the indigenous population is a statement of the overwhelmingly obvious: it is simply a version of the law of supply and demand, that the price of anything falls when supply rises relative to demand.

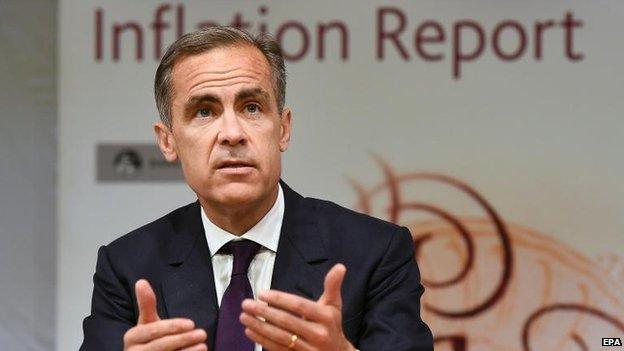

So there is nothing terribly revelatory in Mark Carney saying, at the Bank's three-monthly news conference on its Inflation Report, that immigration had held down the rise in wages and living standards.

Perhaps more interesting is that the Bank acknowledged that it - like the government - had underestimated how much immigration there would be in recent years.

This is what its Inflation Report says: "Net inward migration was close to a historical high of just under 300,000, around 0.5% of the population, in the four quarters to 2014 Q3.

"That is well above the 165,000 per year assumed in the ONS's population projections, which were last updated in 2012, and upon which the Labour Force Survey is based.

"Bank staff have revised up their assumptions about population growth from 2013 onwards on the basis of higher net migration."

So that would imply, on the Dustmann formula, that over two years, immigration had depressed the pay of the poorest by around 0.6% - which is neither devastating nor trivial.

Dampening down?

Which is broadly consistent with what Mark Carney said on the Today programme this morning - though not completely.

The governor wanted - in his words - "to dampen down" the idea that net migration was a big negative factor on productivity and wage growth.

And to prove his point, he said that net migration over the past two years was just 50,000 - which he regards as relatively inconsequential, compared with a net increase in the effective size of the labour force of more than 500,000 due to people retiring later and wanting to work longer hours.

But I am not sure of the source of his 50,000. It is a sixth of the net inward migration statistic cited by the Bank itself for the year to the end of October 2014. And the Office for National Statistics yesterday said that the total number of UK non-nationals working in the UK rose by 294,000 in the year to the end of March (to a total of 3.1 million).

I hesitate to say the governor got it wrong. But the official statistics don't tell his story.

Now there are two other issues here.

First is whether the influx of migrant workers depresses productivity as well as wages.

That looks very unlikely at first blanche. As the Bank points out, the Poles and Romanians who take service sector jobs tend to be overqualified for the work they do in the UK. Often they have degrees. So it is very unlikely that their output would be less than the equivalent indigenous Brit.

However, if the availability of this relatively talented pool of foreign workers is persuading British companies to take on labour to increase output rather than investing in expensive new kit, then that would have a negative impact on productivity - because this failure to invest would means that the output per hour of the workforce would be lower than it would otherwise be.

That said, it would be slightly bonkers to blame immigrants for companies' low investment: that is surely much more to do with their confidence and their culture.

The second important question is whether pulling up the drawbridge and shrinking the numbers of migrants to the UK would be so wonderful for those living and working here.

Well, if the labour market were to tighten, that would probably lead to a welcome increase in wages.

But the Bank of England does not believe there is massive slack in the labour market any longer. And how can there be huge spare capacity, with employment at record levels and unemployment more or less back at pre-Crash levels?

Living standards

So if wage increases suddenly accelerated, at a time when productivity growth remains trivial, they would probably be passed on by companies in the form of higher prices. Or to put it another way, inflation would take off.

What you will already have deduced, of course, is that as soon as the Bank were to see a tightening in the labour market, it would pre-emptively increase interest rates, to choke off demand and any serious rise in inflation.

So if living standards were to rise thanks to a rise in wages, they would almost certainly be simultaneously depressed by a rise in mortgage and other interest rates on households' record debts.

In other words, when the Bank of England talks about the uncertainties and risks built into its forecasts stemming from the uncertain outlook for immigration, its big concern is that interest rates would probably rise faster and more, if the number of workers arriving from abroad suddenly dried up (and if they kept on coming in such large numbers, interest rates would stay lower for longer).

So here is something to chew on: the corollary of the Bank of England admitting that wages would be higher if immigration were a lot lower is that it is also signalling that interest rates would probably be higher too.