Many businesses do not fear leaving the EU

- Published

- comments

A large part of the vitally important debate about Britain's future in or out of the European Union will be based around a simple question which raises a whole host of complicated answers.

What would "out" look like?

For those who back Britain remaining in the EU, the answer is pretty bleak.

If the UK wanted to trade with Europe, the country would still have to be bound by the rules of the EU which would be set - if Britain left - with little regard to this country's opinion.

We would not, those pro-the-EU argue, have a seat at the decision-making table.

In fact, we would be particularly weak because the remaining EU member states might very well want to teach Britain "a lesson" that being out of the union is not a free hit.

The chief executive of JCB, Graeme Macdonald, does not agree.

In an interview in The Guardian this morning, external he says that the UK is far too important a trading nation to be simply pushed to one side.

As an example, he points out that Britain is Germany's fourth largest market for car exports.

Mr Macdonald also argues that being in the EU is not some form of free trade panacea.

"It's easier selling to North America than to Europe sometimes," he says.

The chairman of JCB is Lord Bamford, the Conservative peer and major donor to the party.

In an interview with BBC Midlands, Lord Bamford says: "We are the fifth or sixth largest economy in the world. We could exist on our own - peacefully and sensibly."

This is a key part of the "nothing to fear" argument about the EU and I suspect it will be a strong theme for those who do not reject EU exit out of hand.

Interestingly, the "nothing to fear" formulation has been deployed in the past by two figures who will have considerable sway on the issue within government.

One is Sajid Javid, the new business secretary.

And the other is Jim O'Neill, the former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, who was announced last week as the new commercial secretary to the Treasury, a job with a particular focus on developing economic growth outside London and the South East of England.

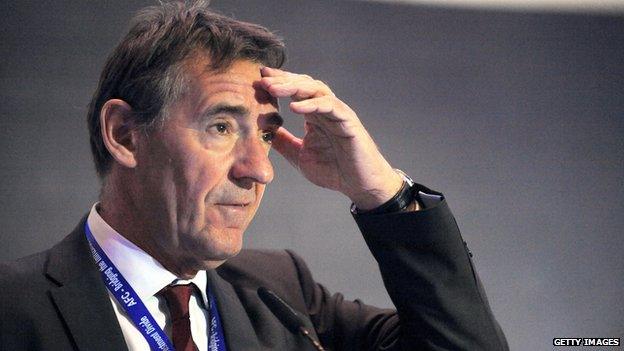

New minister Jim O'Neill said in 2013 the UK should not be scared of leaving the EU

Mr O'Neill is also the man who coined the term "Brics" (Brazil, Russia, India and China) which he believes will form the powerhouses of the 21st Century global economy.

Here he is interviewed in The Telegraph in 2013: "We should not be scared of it [leaving the EU] and exploring a world without it. The opportunities that are arising from the dramatically changing world are huge and I don't think quite a lot of people in our area [the City], never mind people in Brussels, are that interested or understand it," he said.

At lunch with the chief executive of a FTSE 30 company before Christmas, I asked whether he would rather Britain was in or out of the EU.

He argued that it was better that Britain stayed in.

But he also pointed out that if the UK did leave the EU, the company would still retain its headquarters in London.

Why? Because, he argued, the capital is the world leader in global finance and enjoys a regulatory and legal system that is not bettered elsewhere.

As well as a very convenient time zone for those companies that trade in the US and Asia.

Another FTSE 30 company chief executive I spoke to last week was of a similar opinion.

"We operate in over 100 different countries," he told me. "Most of those are not in Europe."

Post the election, the skeleton "no fear leaving the EU" argument is starting to form.

It is based on three premises - Britain is a major trading nation; free trade agreements with fast growth economies will be easier outside the EU; and Britain can rid itself of unnecessary regulations which some believe hold back growth.

Of course, a significant number of businesses disagree, believing that being inside a reformed EU is the best future for the UK.

I was struck during a visit to Japan in 2012 how company leaders there were baffled at the thought that Britain would leave the largest trading union in the world.

What business actually "thinks" about Europe - and where the majority opinion lies - will be one of the defining issues ahead of the in/out referendum promised by David Cameron before the end of 2017.

Eleven days after the election and the arguments are already starting to coalesce.