Will US shale gas bring global energy prices tumbling down?

- Published

The second US shale gas revolution is about to begin.

Vast quantities of fracked gas have already seen domestic energy prices tumble, providing not only US manufacturers but the wider economy with a hefty shot in the arm.

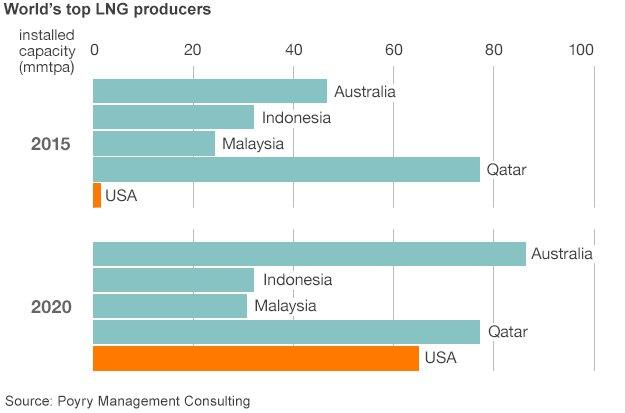

Now the country is looking beyond its own borders to become a major player in global gas markets. In fact, by the end of this decade, the country plans to challenge Qatar, the undisputed king of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Considering the US currently exports virtually no LNG, the scale of its ambition is staggering.

Indeed, if all proposed projects went ahead, it would produce about 190 million metric tonnes (mmt) a year, equivalent to 80% of today's total global LNG market.

US shale gas could, then, have a profound impact not just domestically, but on the rest of the world.

Or so the common narrative goes. The reality will be somewhat different.

Falling prices

No-one ever expected all 20-plus proposed export terminal sites to go ahead, particularly with all that that entails - not least regulatory approval and billions of dollars of financing.

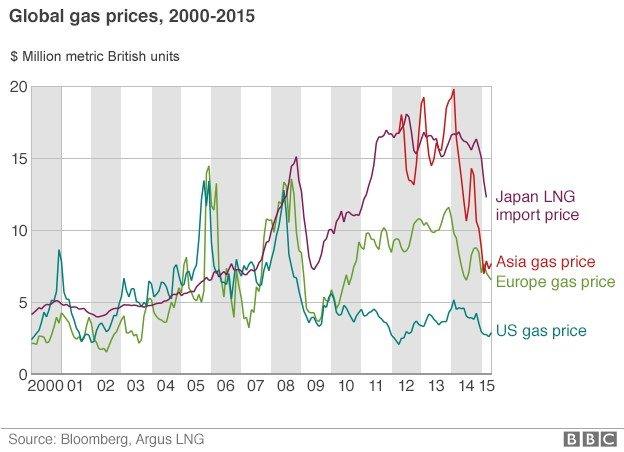

But recent falls in the price of natural gas have played havoc with developers' plans. With US gas prices, known as Henry Hub, hovering around the $3 mark, the economics of gas liquefaction and export depend entirely on getting a higher LNG price in the export market.

Last year, with gas prices in Asia, for instance, up above $15, exporting LNG was a no-brainer. Now the price is about $7.5, as most gas contracts are linked to the price of oil that has plummeted more than 40% in the past year.

Take the basic cost of the gas at $3, add in a small mark up, liquefaction costs of $3 and transport costs of $2, and suddenly, as Luis Barallat at Boston Consulting Group says, "the economics don't work that well".

What is LNG?

Liquefied natural gas, known in the industry as LNG, is simply natural gas that has been transformed into liquid form by cooling to make storage and transportation easier.

Pipelines are fine for taking gas across land, but ships are needed to carry large quantities across oceans.

LNG is a clear, colourless and non-toxic liquid that takes up about 600 times less space than the original natural gas.

A similar story is true for Europe, where cheaper transport costs are offset by a lower gas price of about $6.5.

For this simple reason, export projections have had to be scaled back significantly.

There are currently five licensed export terminals under construction in Texas, Louisiana and Maryland, and with long-term supply contracts signed, they will export huge quantities of LNG in the coming years.

Even if the numbers do not seem to add up, companies buying the gas, such as BG or Gas Natural, may still decide to export - selling the gas in Europe at a $1 loss can represent a better deal than spending $3 on liquefaction and just sitting on the LNG.

Gas is turned into liquid and shipped all over the world, before being turned back into gas

Of the remaining proposed terminals, some have customers but no regulatory approval, while the rest have neither. For now, most of these are unlikely to go ahead.

As Anastasios Giamouridis at Poyry Managing Consultants says: "Without long-term contracts signed with buyers, there is no guarantee of revenue stream, so it's very difficult to get financing."

Political lobbying

Political opposition could be another constraining factor. If producers get a higher price for their gas on the export market, there is little incentive to sell domestically. US buyers would, therefore, be forced to pay more, pushing up domestic prices and reversing a trend that has benefited US manufacturers enormously.

"There is a very strong and well-organised lobby arguing that low prices are a huge advantage for US industry," says Mark Lewis at Kepler Chevreux.

"If the US really were able to export as much gas as it wanted, it would be a very significant political issue."

Another constricting, if rather more contentious, factor could be the impact of falling gas prices on US shale producers themselves, particularly those wet gas drillers producing gas and oil.

Many shale companies are struggling with high debts now that oil and gas prices have fallen

These companies relied heavily on debt financing, partly due to low interest rates, predicated on high oil prices. They are now struggling to repay debts in the face of oil prices that have slumped, in many cases, well below break even point. There are, for example, almost 700 fewer shale oil and gas rigs operating in the US than there were a year ago, with around 800 still drilling.

"I'm surprised the show has run as long as it has," says Mr Lewis. If interest rates rise, as they must, or oil prices remain low, many shale firms will not survive, he argues, raising questions about whether the US can maintain its gas production levels.

The 190mmt a year from all the proposed export terminals was never, then, a realistic figure, but the recent slump in the price of gas has undermined LNG production significantly.

Poyry expects capacity to hit about 65mmt a year by 2020, a similar figure to that forecast by BCG.

Hot air

But this is still a huge influx of new gas to a global market that currently stands at 240mmt. It would make the US the third largest producer of LNG in the world, behind Qatar and Australia, which is also set to increase massively its capacity, from about 45mmt to more than 80mmt by 2020, according to Poyry.

With Henry Hub so much lower than gas prices in the rest of the world, many have assumed this influx will flood the global market with cheap US gas.

But with the total cost of exported US LNG roughly the same as the local gas price in both Asia and Europe, this is clearly not the case. As John Williams at Poyry says: "The US supplying cheap LNG to Europe is a myth. It will be competitive, but nothing more."

If oil prices pick up, pushing gas prices in the rest of the world with them, then US LNG, which is not indexed to the price of oil, could well become relatively attractive.

But with the oil price set to remain relatively low for the foreseeable future, this is unlikely to happen.

What US LNG will do is introduce a major new supply of gas that is far more resilient to fluctuations in the oil price. More importantly, it will boost overall supply significantly, and this will inevitably push prices lower.

But the impact is likely to be short lived, for the very simple reason that demand for LNG is set to rise to meet supply.

"There will be a glut [of LNG] for a while, as demand cannot pick up so fast, but prices will eventually rise," says Mr Giamouridis. Demand for LNG in Europe is currently half what is was just five years ago, and falling prices would see it pick up quickly. There are also a number of new markets buying LNG for the first time, such as Poland, Lithuania, Egypt and Jordan.

Chinese demand for gas is set to rise sharply as it moves away from polluting coal

But the biggest surge will come from China, where demand for energy is expected to triple by 2050, and where pollution is forcing the government to reduce its reliance on dirty coal.

Despite the deluge of new supply, then, global gas prices are unlikely to be affected in the long-term by the US exporting its abundant gas.

The American shale revolution may have seen gas prices tumble at home, but exporting its spoils will have nothing like as dramatic an impact on the rest of the world.