Iran looks to energy reserves for post-sanctions influence

- Published

President Hassan Rouhani is courting global energy firms in anticipation of an end to sanctions

Iran is a bona fide superpower in global energy markets. Or rather it would be if reserves in the ground were the measuring stick.

Taking oil and gas together, only Russia can boast of greater riches.

The potential to be a major gas exporter, then, is huge - were it not, that is, for the small matter of sanctions.

This rather obvious point is not lost on President Hasan Rouhani, who has wasted little time in repairing relations with the West, with one eye firmly on future oil and gas revenues to help bolster his country's ailing economy.

His efforts are very likely to be rewarded in the coming months, as a nuclear deal with the US, the UK, France, Germany, Russia and China that would end sanctions moves ever closer.

Iran has massive reserves of natural gas, mainly held in the South Pars gas field

Iran would then be free, in theory, to flood global markets with huge quantities of gas, offering an alternative supplier to energy hungry nations across the world and dramatically transforming the global geopolitical landscape in the process.

"A deal may not be agreed by this month's deadline, but it has to happen this year," says Jamie Ingram at research group IHS. "There is so much political will on both sides that an extension of two months could be sufficient."

Such a ground-breaking deal would bring a swift end to Iran's enforced isolation.

Huge potential

The country currently produces about 165 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas a year, of which a little less than 10bcm is exported to Turkey, Azerbaijan and Armenia.

It also imports gas from Turkmenistan, but cut back last year to the point where the country is now a net exporter of gas for the first time.

Considering Russia exports almost 150bcm to Europe and has signed deals for a further potential 70bcm with China, Iran's exports are insignificant on the global stage.

But the country is ramping up production fast and is set to produce about 250bcm by 2018, according to Dr Elham Hassanzadeh from Iran consultancy Energy Pioneers. This additional capacity will come from the South Pars gas field Iran shares with Qatar, the biggest of its kind in the world. Beyond 2018, there are already plans for many more phases of development, both at South Pars and other fields such as North Pars and Kish.

The Iranian government wants the country's power industry to use more gas and less oil

Iran has ambitious plans to increase significantly gas production in the coming years

But most of this new gas will go towards satisfying domestic demand. The government is keen to reduce the Iranian power sector's reliance on oil by increasing gas use, in order both to free up oil for exports, generating much needed revenue, and to reduce CO2 emissions. After all, oil does not require huge investment in pipelines or liquefaction to sell abroad.

More energy will also be needed to help fuel economic growth that has been hampered by years of sanctions, mismanagement and corruption.

In the coming years, therefore, Dr Hassanzadeh estimates there will be between 30-50bcm of gas left over for exports each year - a relatively small total compared with overall production, but still a significant amount that equates roughly to Russia's annual gas exports to Germany.

Friends first

Most of this is likely to stay in the Middle East. As Dr Hassanzadeh says, "Iran will focus on the regional market - Iraq, Oman and Kuwait. It will reach out to its neighbours first".

Indeed the country signed a gas supply deal with Iraq in 2013 and the pipeline between the two is all but complete. It is also negotiating the route of a separate pipeline to Oman following a similar deal last year.

The focus will then turn to Pakistan and India. Iran has been talking with Pakistan about a gas pipeline for 20 years and agreement was finally reached in 2010. But while Iran has finished construction on its pipeline to the border, financing problems and political pressure from the US means Pakistan has yet to start.

Iran has signed a deal with Pakistan to supply gas through a new pipeline

Meanwhile, India is not willing to commit to importing gas through Pakistan as relations between the two are too volatile, so liquefied natural gas (LNG) would seem a more likely option. While this is certainly feasible, building liquefaction plants takes many years and billions of dollars of investment, and with a surplus of LNG in the world pushing prices lower, particularly with the US and Australia set to increase exports massively in the coming years, Iran may find energy companies willing to stump up the money hard to come by.

High Price

Next, attention will turn to Europe. "Iran is keen to set up as a competitor to Russia, so Europe is a consideration," says Mr Ingram.

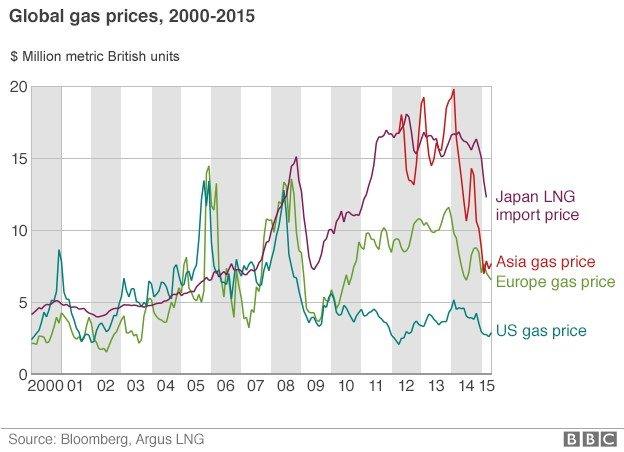

But again cost will be an inhibiting factor. Dr Hassanzadeh estimates that a pipeline to Europe would cost between $5bn-$8bn, and only a consortium of international companies would be able to raise that kind of finance. Again, with international gas prices low, persuading them to invest on such a grand scale could prove difficult for the foreseeable future.

And especially so given Iran has historically driven a hard bargain for its gas.

"The main hurdle in Iran's gas export ambitions has always been price," says Valerie Marcel from the Chatham House think tank in London.

"They need to lock in customers who are willing to pay the price the Iranians want, and without a firm commitment from the buyer, no infrastructure will be built."

Cheap global natural gas prices could scupper a deal in the short term, but this has not stopped Iran from laying the groundwork - Tehran has been entertaining international energy companies throughout the past 12 months in anticipation of an end to sanctions.

And longer term, the overriding strategic benefits to both sides cannot be ignored - Europe is looking to wean itself off Russian gas, while Iran is looking for diplomatic leverage that would make the re-imposition of sanctions far harder to countenance.

As Dr Hassanzadeh says, "we are a very ambitious nation", and one, like many others, that is eager to gain influence on the international stage. Its huge reserves of natural gas offer a tantalising opportunity to do just that.