Is gas a weapon in the fight against climate change?

- Published

The bosses of the four biggest polluting companies in history talking about how they can help solve global warming may seem like the height of hypocrisy.

Chevron, Exxon Mobil, BP and Shell are responsible for more than 10% of all greenhouse gases emitted since the industrial revolution, and yet here they are, talking under the banner: "Natural gas as a core pillar for a sustainable future of the planet".

Exxon boss Rex Tillerson manages to use the word environment 13 times in his opening address. "[Our industry] can deliver significant environmental benefits", he says, while Shell's Ben Van Beurden follows with "gas can help in securing a sustainable energy future."

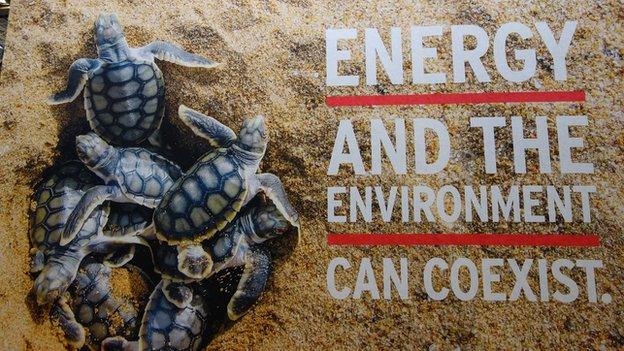

These comments reflect the key theme at this year's World Gas Conference in Paris, as energy bosses look to rebrand their fossil-fuel businesses as a crucial weapon in the fight against climate change. (Or rather half their businesses - there was no mention of the fact they are also major oil producers).

Delegates were left in no doubt about the key theme of this year's World Gas Conference

But this is not as ridiculous as it may seem.

For a start, their argument that natural gas emits half as much CO2 as coal and should, therefore, be used to support renewables, is legitimate. As is the point that US CO2 emissions have fallen sharply on the back of shale gas discoveries.

But more importantly, this attempt to disassociate gas from coal and oil, and present it as a cleaner fuel source, shows that energy companies have accepted the fact that reducing CO2 emissions is now firmly established on political and, increasingly, corporate agendas across the world.

Polluter pays

A number of energy companies have signed up to the World Bank initiative to end routine gas flaring by 2030 - a process of burning off excess gas at extraction that emits about 300m tonnes of CO2 every year.

Many, including Total, BP and Shell, have also made a joint call for an effective carbon price, which would force big polluters to pay more for the CO2 they emit. This may seem odd given these very same companies will be hit, but this call is clearly out of self interest - the biggest rival to gas is coal, and coal producers will be hit far harder.

Gas companies are very keen to champion their environmental credentials

Coal is cheap and abundant, and the only way gas producers can compete on price is if carbon is taxed, even if this means the oil side of their business suffers.

But it's not just about CO2. Many gas executives are at great pains to highlight the growing problem of air quality around the world, particularly in China.

Gas, Mr van Beurden says, emits 90% fewer air pollutants than coal, a fact that should not be overlooked in a world where there are seven million deaths linked to pollution every year, according to the World Health Organization.

Flexible fuel

And just as gas cannot compete with coal on price, it cannot match the environmental credentials of renewables. The gas industry has responded by saying the two complement each other perfectly. It argues renewables, such as solar, wind and hydro power, cannot alone meet the growing demand for energy, which is estimated to rise by as much as 40% in the next 20 years.

Just as importantly, executives say, solar and wind power are variable, so gas is the most environmentally-friendly fossil fuel to act as a back up when renewables cannot satisfy demand. Gas plants are also relatively flexible and can be turned on and off more quickly and cheaply than coal and nuclear plants.

Gas companies went to great lengths to attract the interest of delegates

And they also point to the potential of gas for storing energy from renewables. Batteries are grabbing all the headlines, but gas offers a viable alternative, particularly for larger-scale storage.

Finally, gas can be used to power vehicles with much lower emissions than oil-based petrol or diesel. Argentina, for example, has more than two million natural gas vehicles, with Brazil not far behind.

All of this means that "gas is not part of the problem, but part of the solution," Mr Dudley says.

Cutting emissions

This is all well and good, but the simple fact remains that despite the industry's efforts to convince us otherwise, natural gas remains a fossil fuel that emits harmful CO2. And lots of it.

So simply switching from coal to gas is not the answer. In fact, if all the coal power stations in the world were turned off and replaced with modern gas-fired plants, total global CO2 emissions would fall by about five billion tonnes a year to 25 billion tonnes, according to Laszlo Varro at the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Emissions need to fall to about five billion tonnes for the climate to stabilise, he says.

Gas companies from all over the world spared no expense at the World Gas Conference in Paris

Iran has huge gas reserves which it could export to Europe if sanctions are lifted

One way to make gas cleaner is carbon capture and storage (CCS), but the world has been very slow to develop this technology - there is just one commercial scale CCS coal plant and no gas plants.

What is clear, however, is that as things stand, renewables alone cannot satisfy the world's growing demand for energy. In theory, it would be possible to power the world solely with solar panels, but variability remains the major drawback. And while batteries can be used to store energy during the day for use at night, they cannot store energy in the summer to use in winter.

This is why "we are going to continue to need conventional power generation for a long time," says Mr Varro. And as gas is the cleanest fossil fuel, it is "the best candidate for filling the gap", he adds.

For this reason natural gas use will grow significantly in the coming years, potentially to the point where it overtakes coal and oil as the world's preferred hydrocarbon. At some point in the next 20-30 years, however, gas use will have to start falling to avoid dangerous climate change.

This reliance on gas could be reduced significantly if governments invest in large-scale energy storage systems and, more importantly, in renewable energy that is not variable, such as tidal and geothermal.

The technologies to wean ourselves off fossil fuels are available. The problem is, with current models of financing, developing them at scale is, for now, proving too expensive.