How to have a life beyond work

- Published

Leadership expert Steve Tappin warns that chief executives whose only focus is work risk burning out.

"Work and life is the same thing for me," says Jake Park - the founder of South Korean start-up firm VCNC.

Like many young entrepreneurs, his work has become all consuming and he doesn't mind in the least, saying his company - which has created a mobile app to allow couples to create and remember special moments called Between - makes him happy.

"I'm happy when I work and, I'm really happy when I see the people who use my product. Making our users happy, makes me happy," he says.

Jake Park says for him there's no difference between work and life

But nurse Bronnie Ware - who spent years caring for people at the end of their lives - suggests it's a different story once people get older.

Her book based on her experiences - The Top Five Regrets of the Dying, external - found one of the most common sources of sadness was "I wish I didn't work so hard", with men in particular "deeply regretting spending so much of their lives on the treadmill of a work existence".

It's a salutary tale for those dismissive of the work-life balance issue - a phrase so common that it's practically become a cliche.

Research suggests that advances in technology giving employees the ability to check their work emails 24 hours a day have made it even harder for people to separate work and life.

Management consultancy Deloitte's global survey, external of 2,500 business leaders found two thirds of employees were feeling "overwhelmed" with 80% wanting to work fewer hours.

'Useless course'

Sir Martin Sorrell confesses he was initially sceptical of the issue. At business school, he dutifully drew three intersecting circles representing career, family and society to score top marks in an exam, but admits he thought it was a "useless course".

Years on having built WPP, the advertising firm he founded, into a global giant, and having gone through a divorce he says he failed the real life version of that particular course, and knows "very few people" who have managed to achieve a genuine balance.

"The stresses and strains from each of those three vary over time. You know, sometimes family demands are greater, sometimes societal demands... are greater, sometimes your career demands are greater. But balancing those three I think is exceptionally important," he says.

Walter Robb (left) and John Mackey share the burden of the top

'Workaholic culture'

Yet for those at the top, admitting they need a break can be perceived as a weakness,

John Mackey, co-founder and co-chief executive of supermarket chain Whole Foods says in the US a "workaholic" culture means people often boast about how long they work, seeing 80-hour weeks as a badge of honour.

He admits he himself has worked such long hours, but says it's not sustainable in the long term.

In an effort to reduce the workload of being the boss, he divides the top role with co-chief executive Walter Robb, and they are part of a seven-strong executive team which all earn the same salary and share executive responsibilities.

"Walter and I may be the leaders of that group but we all are working together," he says.

This approach continues throughout the firm, with individual stores having control over budgets and staff having the power to make decisions.

This structure, gives him time, to meditate, exercise and eat well, he says.

While it is easy to be sceptical about an approach that appears to have come straight from the 1960s hippie era, the results suggest it is effective. The firm most recently reported record sales for its second quarter and for the past 18 years in a row, it has been listed as one of the "100 Best Companies to Work For" in the US by Fortune magazine, external.

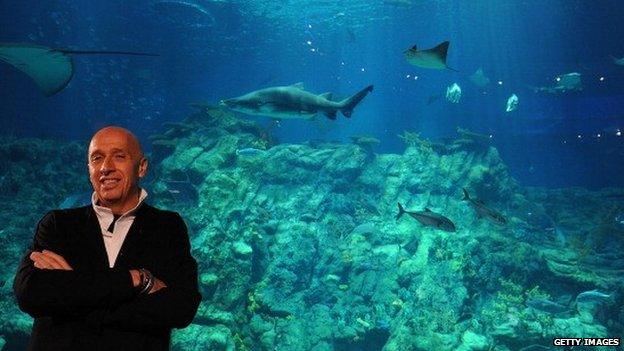

Allan Zeman does 90 minutes of exercise every morning without fail

Many of those at the top believe focusing on their health - in particular regular exercise - is the main thing that enables them to tolerate the pressure of being in charge.

The father of Allan Zeman, chairman of the Hong Kong-based Lan Kwai Fong Group, died of a heart attack when he was just 50.

Wanting to avoid the same fate, Mr Zeman says he is absolutely regimented about fitting 90 minutes of exercise into his diary every morning - even on one occasion keeping a US president waiting while he was doing his routine.

"Exercise helps to clear your body, helps to clear your mind. The more you abuse your body, the more stress you put on your body, it will hinder you from doing good business or being a good person. So I try to balance the things I do," he says.

Helena Morrissey says being in charge makes it easier to juggle her responsibilities

Being at the top can also make it easier to take time out for other things because bosses don't normally need to ask for permission to take a break.

Helena Morrissey, chief executive of fund management firm Newton and the mother of nine children says being in charge makes it easier to juggle her different responsibilities.

"I want to encourage other women who might be looking and thinking how can I do all of that, to keep going until you get to that point where you do have a little bit more control," she adds.

Tim Brown, chief executive of design firm IDEO, has done exactly this. He adopted the "10 day rule" practised by a company founder which meant never spending more than that period of time apart from his wife.

"Making sure that I don't spend too long away has made a huge difference to our relationship and therefore a big difference to my life. So I think in terms of quality of life, that was probably the best piece of advice I ever got," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.