The options for Greece

- Published

Yet another deadline is approaching in Greece.

Yes we have had them before, but this does look serious. There's a payment due to the IMF at the end of the month. If Greece and the eurozone can't agree to release delayed bailout money, that payment could be missed.

The Bank of Greece - part of the wider eurozone central banking system - has warned, external that could set off a chain of events ending with departure from the eurozone and probably the European Union, with some severe economic consequences.

In fact, the timing gets more complicated. The IMF managing director doesn't formally notify her board that a payment has been missed until a month after the due date - although it's hard to believe they wouldn't have heard about it on the grapevine.

And in the the interim, there is another, even larger payment due to the European Central Bank. So there is little time, though the financial world doesn't come to an end for Greece at midnight on 30 June.

What Greece is now doing is negotiating with the eurozone and the IMF the economic policy programme to follow if the remaining bailout money is to be paid out.

There are differences over the borrowing targets for the government finances, how to meet them - especially on pension cuts and value added tax increases - and whether Greece should receive debt relief.

So what position might a Greek negotiator be taking? And what are the pluses and minuses?

Option 1 is to hold out for a while to see what they can get but they are desperate for a deal and accept that they will give in to the demands of the creditors if that is what it takes to get them to sign on the dotted line.

The benefits are straightforward. The long delayed bailout payments would be made. Greece would be able to avoid defaulting on its debts.

The drawbacks are also pretty obvious. It would mean signing up to a programme of policies that includes further austerity and some specific measures to meet the budget targets, measures that the Syriza-led government hates: further cuts in pensions and reforms to value added tax.

The result would be dissension in the party and outrage among people affected. And in all likelihood further headwinds for the struggling economy, which has gone back into recession. There would have to be negotiations for further financial help - a third bailout and probably debt relief. More political torture for the government at home and internationally.

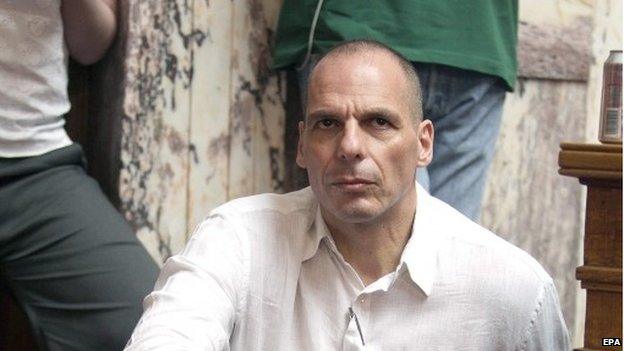

Yanis Varoufakis says Greece is "determined not to be treated as a debt colony that should suffer what it must"

Option 2 is no surrender - utter determination not to give in and a conviction that the other side will buckle at the last moment.

If it works, it is the most appealing to the Greek negotiator. They get the delayed bailout money without having to take the immediate pain of option 1, though there is still the thorny question of making the government's finances sustainable in the long term.

Why might a negotiator believe this would work? Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis argues that a Greek exit would do untold damage to the rest of the eurozone. He doesn't appear to believe it when the other side says they could cope with the financial and economic fallout, much better than would have been the case earlier in the crisis.

There is also a desire in Brussels, Berlin and other EU capitals to avoid undermining the idea that the euro is forever. They would also be uneasy about the possibility of a failed state on the EU's southern flank, perhaps getting diplomatically closer to China and Russia.

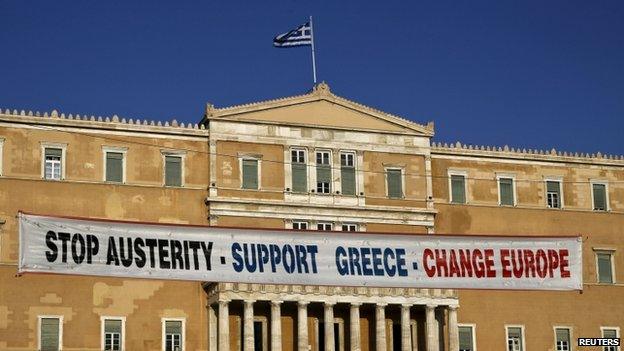

The Greek public are against austerity but want to keep the euro

Option 3 is no surrender, but with the acceptance that the other side might also dig their heels in. That would mean default on the debt payments coming due, perhaps the one owed to the IMF at the end of the month or to the ECB in July.

That doesn't necessarily mean exit from the eurozone, but it could trigger a chain of events that leads there. The European Central Bank would have to consider pulling the plug on the country's commercial banks, because a government default would raise new doubts about their solvency.

That in turn could lead to severe financial restrictions and perhaps a Greek decision to start printing their own currency, partly to keep the banks afloat. So there is a possible path that leads from failure in the negotiations to default and to a Greek exit from the eurozone.

There is a high political price in following that path. Greek public opinion is overwhelmingly in favour of keeping the euro.

Economically it would certainly be disruptive in the short term. In the longer term, some argue that Greece would be better off with its own currency to devalue and improve competitiveness and control of its own economic policies. But banking on that would be a huge gamble.

There could still be some waiting for a deal

Option 4 is more delay. Maybe give a little ground, enough to persuade the eurozone to extend the negotiations for a few more weeks or even months, and perhaps make small bailout payments to prevent immediate default.

That avoids an immediate economic conflagration in Greece. But the dark cloud of uncertainty would hang over the country's economy - which went back into recession at the end of last year. The tension - or you might say the tedium - would be prolonged ever further.

Delaying decisions is something that both sides have shown themselves to be very good at during the eurozone crisis.

It could even drag on into August and disrupt the summer holiday in many European countries. If they let that happen it would be a sign that they are really taking it seriously.

What to look out for in the next two weeks

Thur 18 June: European finance ministers meet in Luxembourg - this is the last chance for either side to cave in, according to some officials, so could be a late-nighter

Sun 21 June: If there is any prospect of a solution being within reach the EU could call an emergency meeting of European leaders

Mon 22 June: If no deal has been reached, Greece may have to start considering capital controls on its banks or other measures

Wed 24 June: The ECB is expected to review the financial support it gives to Greek banks. It can only supports banks that are fundamentally solvent

Thur 25 June: EU summit - the very, very last chance to do a deal. Greece is not currently high on the agenda but it may force its way up depending on the circumstances

Tue 30 June: Greece's current bailout expires. This may prompt the ECB to reconsider its support for Greek banks. By now, Greece should have paid €1.6bn (£1.1bn) to the IMF

Wed 1 July: The country could now be in arrears at the IMF. If so, it would be hard for the ECB to continue any support it is still giving to Greek banks

Are you in Greece? What are your feelings about the future? Do you have a pension? You can share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk.

Please leave a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist.

You can also send your comments to us on WhatsApp +44 7525 900971