From TV blackout to a Premier League broadcasting fortune

- Published

Watford v Liverpool in the second game on English TV screens in 1985-86, shown on the BBC

The Premier League kicks off again this weekend, and for fans raised in an era of wall-to-wall live televised matches it will be a shock to learn that 30 years ago the 1985-86 season began with not a minute of live action shown on TV.

In fact live club football did not return to the screens until January 1986 after a bad tempered war of words between the Football League, which ran the top flight then, and broadcasters at the BBC and ITV.

They were wrangling over a deal offered by the TV firms worth just £19m over four seasons, about £55m in today's money.

The Football League chairmen felt that the true value was closer to £90m.

Cut-price deal

However, unlike now, 30 years ago the TV companies - not football clubs - held the upper hand, and when no agreement could be brokered (there was also a row about the split between live games and highlights) they had reached an impasse.

As a result, there was a football blackout for the first half of the 1985-86 season, and in the second half, only 13 English club games were shown live.

The Football League had capitulated in December 1985, accepting a pitiful £1.3m (£3.74m now) for nine First Division and League Cup games. A separate FA Cup deal was also signed for four games.

Trevor Hebberd (left) of Oxford United scores v QPR in the 1986 League Cup Final

* The BBC and ITV both also showed the FA Cup Final live as normal. The 1986 European Cup Final, and England v Scotland were also broadcast live.

'Battering ram'

"It is strange to look back and realise there was nothing more than a few games shown live on TV that season," says Robin Jellis, editor of respected industry journal TV Sports Markets.

"Things have changed beyond recognition since then. There has been the advent of pay-TV, and the need for premium content - such as Premier League football - to drive sales.

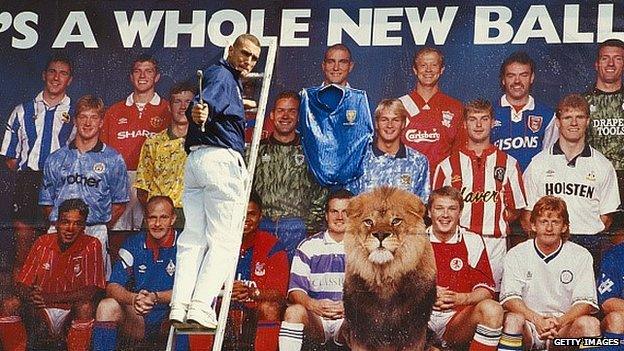

Sky's winning of the first Premier League rights ushered in a new pay-TV broadcasting era

"In fact, there is now so much football content that new sports channels are constantly appearing to handle the volume."

Mr Jellis points to the 1992-93 launch of the Premier League as a watershed moment for football on TV, and Rupert Murdoch's vow to use sport as a "battering ram" to sell Sky pay-TV subscriptions.

It was that deal which kick-started the ever-increasing sums paid for rights over the past two decades, during which time other broadcasters such as Setanta and ESPN have entered and left the fray.

Rights 'inflation'

Back in 1986, after the blackout season, the BBC and ITV then agreed a deal worth £3.1m a season (£8.4m now) to the football authorities - less than the money they had been offered in 1985 - covering the following two seasons.

Each broadcaster would show seven live games each a season.

Compare that with the forthcoming 2015-16 season, the last year of the current Premier League deal with Sky and BT, which is worth £1bn a season for 154 live matches.

BT Sport's entry on the scene has helped push up the price of Premier League TV deals

And those figures are dwarfed by the £1.72bn a year deal the Premier League has secured for the three seasons from 2016-17 to 2018-19, for 168 matches a year.

"The current inflation is the result of competition between Sky and BT. Sky's whole business model is based around the Premier League football TV rights, and securing of the majority of the games," says Mr Jellis.

"BT's number of games is smaller, but they are coming to it from a different perspective. They saw their broadband customer business being lost to Sky, and their aim was always to stop that migration."

Frank McAvennie of West Ham United was a beneficiary of the TV blackout

John Motson, BBC Football commentator, remembers 1985-1986

"Football was a totally different product to what it is today. It had gone through a very bad period in a PR sense, with the Bradford fire, riot at Luton, and Heysel disaster.

"Football, it seems strange to say now, became unfashionable for a time, it was not dominating in the newspapers, and of course TV coverage was off air from the start of the season until January. The mood was one of disillusionment.

"The crowds at some of the old First Division grounds were not great, I remember just 12,000 at a West Ham match.

"There was a gradual uplift, some put it down to the 1990 World Cup, others to the founding of the Premier League. Some would say the nadir was Hillsborough, but the Taylor Report which followed ushered in new, all-seater, stadiums.

"Strangely enough, having no live football on TV for the first half of the season benefitted one player, Frank McAvennie, who had signed for West Ham from St Mirren. Only West Ham fans had really seen him in action, and the unknown factor meant he was able to score 18 goals in the first half of the season.

"I commentated on the first live game back on television in January 1986 for Charlton v West Ham in the FA Cup, and when McAvennie appeared on screen I said 'now you know what he looks like'."

'Aggressive bidding'

Looking further ahead, to the next domestic deal cycle, which would begin in season 2019-20, Mr Jellis says possible threats to Sky and BT could come from Discovery, which has just secured future Olympic TV rights in Europe, and BeIN, Al-Jazeera's rebranded sports channel, which is becoming increasingly acquisitive.

"I can't see there being anything but increasingly-aggressive bidding in three years time," says Mr Jellis.

Increased TV money has allowed English clubs to sign foreign stars

"Premier League clubs are certainly benefitting from the competition. The influx of top foreign players is because of the big salaries that can be offered as a result of the TV deals.

"The amount of money the clubs are getting is already vast, and that is going to increase even more."

He says that while the team that wins Serie A in Italy earns roughly between €30m to €40m (£21m to £28m) in broadcasting revenues, estimates show that the team that finishes bottom of the Premier League in 2016-17 could earn up to £100m from TV monies.

Overseas rights

Ever-inflating bubbles have a tendency to burst, but Mr Jellis believes that moment - if it ever arrives, is still some way off, especially as the Premier League has still to sell the next tranche of its international TV rights.

Those rights are worth about £2bn in the current deal cycle, and the Premier League has launched tenders for bids in two of its most lucrative regions - the US and MENA (Middle East & North Africa).

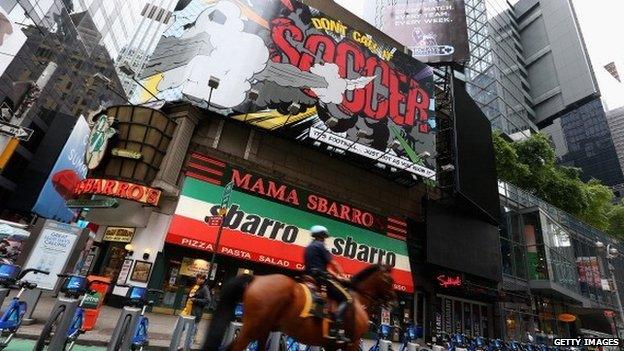

Mr Jellis believes that, as in the UK, the rights are about to soar overseas. US rights are currently with NBC Universal at $83m a season, but he believes that is set to more than double.

NBC billboard in New York promoting its TV coverage of the English Premier League

In addition, BeIN and rival Abu Dhabi Media could also be set to fight it out in the Middle East.

"Another huge market is Asia and South East Asia, as seen in the relentless Premier League club touring there," he says.

Back in the UK, some other factors could also be in play in the run-up to that next domestic deal, beginning in 2019-20.

"Quad-play could be a huge factor then," says Mr Jellis, referring to a communications bundle that includes high-speed data, telephony, TV, and wireless.

"The fruits of what Sky and BT are looking to put in place now won't be known until then. We also have BT looking to tie up its deal with EE, to give it that mobile platform.

"If the competition authorities give that the go-ahead then I think we will see Sky look to do something similar with a mobile operator."

Changing channels

However, a visitor from the mid-1980s would be totally confused by today's TV football landscape.

"The idea of buying a subscription to watch live football, or the notion of these new platforms that are available to watch football on - the internet, mobile devices - would not have been imaginable 30 years ago," says Mr Jellis.

"All you had then in 1985 were the handful of terrestrial TV channels. Football viewing in the UK has totally changed since then."