Is there any way Greece can avoid default?

- Published

- comments

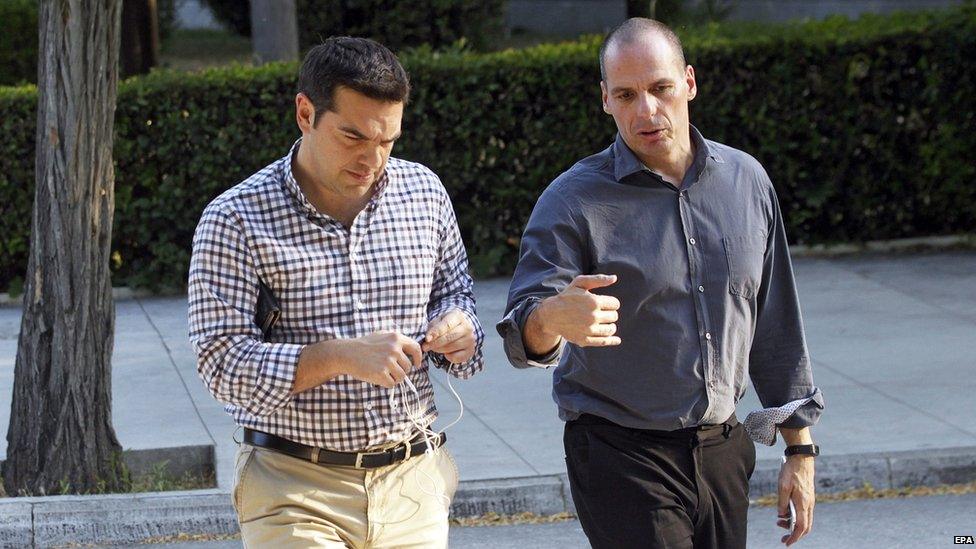

Tsipras and Varoufakis

Part of what divides Greece and its creditors is the detail of budget cuts and economic reforms demanded by eurozone governments and the IMF.

And the rest of the gulf is due to a monumental clash of expectations between the scope of what can be agreed by the deadline of 30 June.

What is clear both from what the Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis said last night and has released in his blog, external is that he is still arguing for a once-and-for-ever settlement - that includes a further reconstruction of Greek public sector debts to make them more sustainable.

He is arguing for a buy-out by the eurozone's financing arm, the ESM, of the European Central Bank's 27bn euros of loans to Greece - because the repayment schedule on these loans (or bonds) is yet another accident waiting to happen.

But although Varoufakis is doubtless right that it would be rational to pre-emptively remove this threat of probable future defaults, the eurozone is institutionally incapable of doing so at this juncture. It completely lacks the decision-making capacity - such is the dispersal of power between the member states and their respective parliaments.

Part of the sub-optimal political and economic compromise that is the eurozone, is that it can't chew gum and walk at the same time. Greece needs to wake up to this inescapable if disappointing reality.

And if Greece's government, led by Alexis Tsipras, wants to avoid default, it needs to concentrate on two issues in particular.

First there is the now small gap between Greece and the creditors on the scale of austerity required by 2018 - which has shrunk to the equivalent of just 0.5% of GDP in 2016.

Second is the demand by the creditors for cuts to Greek pensions.

Varoufakis argues persuasively that there have already been 40% cuts imposed on Greek pensioners, and a further cut would be devastating for many poor Greek families - because high unemployment makes them dependent on help from grandparents.

But if further cuts are socially and politically impossible for Syriza's government, it needs to come up with some kind of bankable counter-offer.

Because what was clear from briefings last night after the collapse yet again of the rescue talks is that the eurogroup and IMF are open to credible offers of budget savings to be found in other ways.

If the Greek government could find just one symbolic and money-saving measure, it seems fairly clear that a deal can still be done to release the crucial additional euros desperately needed by Greece to avoid default.

Or to put it another way, Tsipras and Varoufakis need to swallow their pride and see the creditors not as a vicious running dog of capitalism that wants to savage and humiliate their proud country but as a slightly bewildered and still young mongrel that just wants to be thrown some kind of bone.