Navigating the potentially murky world of online reviews

- Published

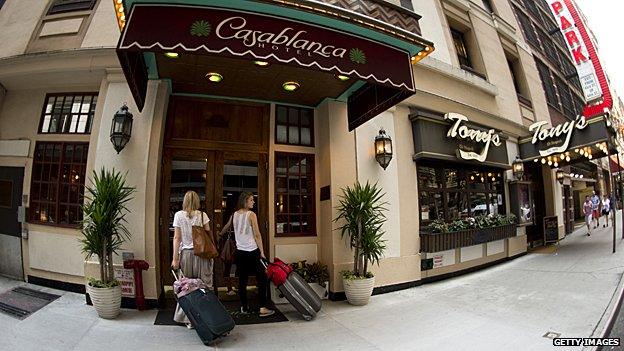

Negative feedback: Online review sites should push businesses to improve their facilities. Some have decided paying for fake reviews is an easier way to go about things

"Write Reviews Get Paid", screams the advert.

This might sound a theatre critic's dream, but Craigslist's "Get $5 for Yelp review" leaves less room for such notions.

It's the seamy side of an online reviews industry which has enticed clickfarms in Bangladesh, lawyers in London, and New York's Attorney General.

And now, the UK's Competitions and Market Authority (CMA) as well, which is opening an investigation using its consumer enforcement powers, and pondering further action.

The CMA is also planning an international project on online reviews and endorsements, to coincide with Britain's year-long presidency of the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network, which starts 1st July.

It's big business, these new crowdsourced yellow pages of the internet. A hearty 62% of British consumers say they are likely to be affected by positive online reviews - with negative ones, that soars to 89%.

Adds frequently appear on Craigslist and other similar listings sites offering money for fake reviews on Yelp

Positive feedback

Once upon a time, we kept our stiff upper lips, and we kept online opinions stoically to ourselves.

Then along popped Amazon and eBay in 1994 and 1995, and with them our habit of scrawling online our joy or chagrin with each latest acquisition.

We now measure ourselves and businesses against an economy of likes, follows, and stars.

One in sixteen of the people online across the world visited TripAdvisor last July. The website gains 139 reviews each minute.

Trustpilot's partnership with Google means it provides many of the ratings provided with the search engine's results.

And Yelp's 77 million reviews pulled in 142 million visitors in the first three months of 2015.

Restaurants which increase their ranking on the platform by one star raise revenue by 5-9%, according to Harvard Business School assistant professor Michael Luca.

Likes mean lucre.

The Casablanca Hotel in New York is consistently near the top of the list of the city's hotels - prompting between 100,000 and 180,000 views a month

Performance anxiety

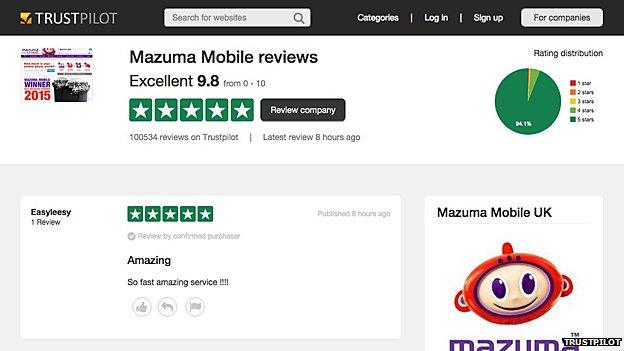

"Negative reviews are the most useful because they continue to challenge our methods, and teach us more about what our customers want," says Charlo Carabott, managing director of Mazuma Mobile, a Watford mobile phone recycling company.

He says his company engaged with an early spate of negative reviewers, publicly answering their complaints, and now boasts a 9.8 out of 10 TrustScore on Trustpilot, with 100,000 reviews.

But for every business like Mr Carabott's, there's another with a more negative reaction. Some will even turn around and sue their critic. Others pen fake reviews, then slate their competition.

London-based Pimlico Plumbers sued Yelp in 2014 for "defamatory and disgusting" reviews.

They were ultimately taken down as part of a settlement, says Vince Sollitto, Yelp's senior vice president.

He says anonymous speech is better protected in America than in England and Wales, where websites can be required to hand over a reviewer's identity under the Defamation Act of 2013.

"It never makes sense to sue your customers."

A quarter of companies have taken legal action over online reviews. In nine-tenths of cases where a review is removed, it is because of a threatening legal letter, says Canadian home-improvement ratings site HomeStars.

A feast for crows if you're a lawyer. HomeStars has introduced a bully warning for businesses that have sent it or reviewers legal letters.

And New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman announced in September 2013 that 19 companies had agreed to cease posting fake reviews and pay penalties from $2,500 to $100,000 (£1,600-£64,000, €2,225-88,990 ).

The companies ranged from a dentist, a cosmetic surgery, an adult entertainment chain, and the charter-coach giant US Coachways.

Mazuma Mobile is proud of their 9.8 ranking on Trustpilot

A reviews racket

"It would seem 10-30% of online reviews are fake, based on what I've seen," said a veteran of this investigation in the New York Attorney General's office, who did not wish to be named.

The typical business leaving fake positive reviews - known as boosting - has either few reviews or a recent crop of negative reviews. Companies also write fake negative reviews - vandalising - attacking the competition.

"At the moment, we will have around 3% of the reviews that are flagged, that's either proactively by users or by ourselves," says Trustpilot's James Westlake. By context, he adds, the website has one new review every five seconds.

Independent businesses are more likely to post fake positive reviews than chains.

"The reason is quite simple. When was the last time you checked a review of Burger King or McDonald's? Nobody does that," says Dr Georgios Zervas, assistant professor at Boston University, who studies internet markets.

He says the number of reviews rejected as suspicious by Yelp, 16%, at present, has increased yearly.

Inside Yelp's New York offices

There are several telltale signs of fake reviews. They are often shorter, and more extreme, clustered at either end of the scale.

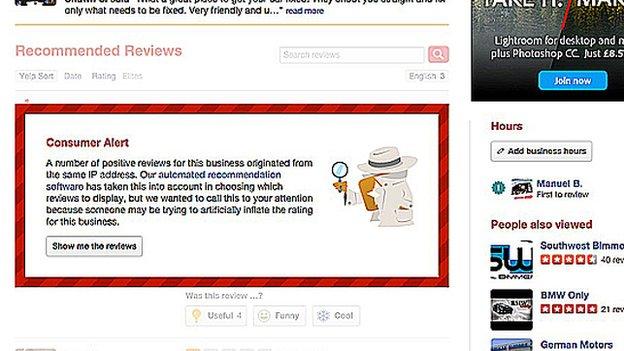

Too many reviews, or from the same IP address, at the same time is another sign, says Jenny Sussin, an analyst with technology research firm Gartner.

So are too many superlatives. And too many adverbs.

TripAdvisor uses "approximately 50 filters", applied by automated systems, says Adam Medros, who heads its product development.

Paid fake reviewers are recruited online

Borderline cases go to human analysts, of whom there are about 300.

"You have interconnectedness of attributes between people, devices, and locations that aren't normal, and they stand out against backdrop of normal behaviour," he says.

Firms suspected of doctoring reviews receive a scarlet letter, a red badge alerting readers that reviews submitted for that business have raised suspicions.

It's a cat and mouse game, says Mr Medros, which he confesses he finds geekily intriguing.

"There's always going to be an arms race, a little bit, around the tech different people are using, and the ways we use to detect them," he says.

"They're getting better, we're seeing this in past years," says Trustpilot's Mr Westlake.

"We identify fraudulent activity and it morphs, like a cold virus."

Inside Trustpilot's offices

Book(ing) reviews

Many scammers are recent computer science graduates from developing countries such as Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines.

In the short term, it is easy for them to fake an IP address, but harder to manage this at scale without tripping alarms.

Websites like Yelp have also engaged in more cloak-and-dagger ways to tease out illicit behaviour, posing as scammers, or businesses searching to hire them.

If those caught cooperate, it is another source of intelligence into the other side's dark arts.

A Yelp red flag, indicating that some of the reviews for a business have come from the same IP and may be fake

It's not just Yelp and Tripadvisor reviews that are bought - bloggers too are offered cash and goods to post positive reviews

"It turned out we were able to get people to admit they were fake," says the specialist from the New York Attorney General's office.

"It was a combination of people coming clean, and the occasional email providing enough of a gotcha," he says.

So why are companies engaging in this behaviour?

Part of the reason, suggests Yelp's Mr Sollitto, could be local small businesses are the last part of the business world to be brought online.

Most still spend nearly all their advertising budget in traditional ways, even as studies show consumers searching for and finding them online.

"Partly, they get to control the message, the copy, the one-way advertising, even though the reality is that no longer works," he says.

It will take some time for the small business market to come to accept "all these old-fashioned methods are worthless".

"What really matters is online, and online you can't control a message. You can only earn a reputation."