The challenges of going global

- Published

Going global is often the only way for successful companies to keep growing, says leadership expert Steve Tappin.

Online auction site eBay is one of the world's best known firms, boasting 157 million active buyers and reporting just shy of $18bn (£11.4bn) in revenues last year.

Yet when it first tried to launch in China it failed. The difficulty of competing with local rivals meant that in 2006, a mere two years after entering China, it was forced to admit defeat and shut down its main website in the country.

Instead it formed a joint venture with a local partner to help operate an online auction business in the country.

Critics say it failed to recognise that having a strong US brand would not automatically translate to success in China.

And eBay is not the only firm to struggle with transferring a successful business model overseas.

Critics say eBay failed to recognise that having a strong US brand would not automatically mean success in China

Tesco reportedly spent a decade preparing for the launch of its Fresh & Easy chain on the West coast of America, with its top executives even spending time living with Californian families to observe the way they lived and ate.

Yet six years after it opened, it announced it was pulling out - costing the firm a hefty £1.2bn.

Similarly one of the world's best known brands, US giant Starbucks, was forced to close almost three quarters of its shops in Australia just eight years after it opened them, after it struggled to win sales from local competitors.

A matter of survival

Business leaders share their tips for firms seeking to expand overseas.

Despite the difficulties, international expansion is often the only way for firms to increase sales. When domestic growth has stalled, other countries can provide a business with fresh customers potentially in an area with less competition or where demand for a particular product or service is higher.

And of course, having a presence in more than one country ensures a firm isn't reliant on the health of just one country's economy for its success.

Over half of businesses (55%) saw a positive impact on their bottom line within just twelve months of expanding into international markets, according to the British Chambers of Commerce recent survey of 4,700 companies.

Ultimately, it's a matter of survival, says leadership expert Steve Tappin, who says that going global is often the only way for successful companies to keep growing.

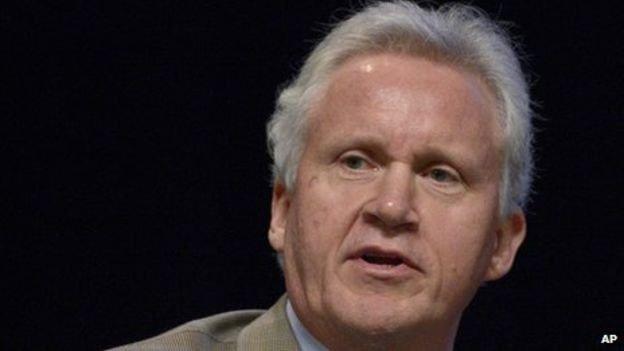

GE boss Jeff Immelt says over half of the firm's revenues now come from overseas

'I've got to win those countries'

When Jeff Immelt, chief executive of US giant General Electric (GE), took the helm over a decade ago, some 70% of its operations were in the US.

Now it operates in more than 160 countries and over half of its revenues come from overseas.

For him, targeting deals in developing countries is a top priority because their rate of growth vastly outpaces that of the US and he says GE will never be so US-focused again "unless we are failing horribly".

"I sit in my office every day and say I've got to have higher market share in China than I have in the United States," he says. "I've got to win Brazil, I've got to win Africa. There's no choice. I've got to, I've got to win those countries."

A high population and limited land can make farming expensive in China prompting some Chinese companies to look overseas

Hiring locally

Similarly, Liu Yonghao, chairman of New Hope Group - one of China's largest agriculture businesses, says the high population and limited land has made production in its home country expensive and forced it to look overseas to lower its costs.

It's taken the firm almost two decades to build about 50 factories in 30 countries, with different focuses on production, distribution and trade, research and development and services. And now overseas sales account for a tenth of total sales.

Mr Liu says one of the biggest lessons it's learnt is that relying just on Chinese managers to run overseas divisions is not the best approach.

Recently, when it acquired an Australian firm of around 800 people, it sent just three Chinese board members to the firm and kept the main positions of authority including chief executive, sales director and chief financial officer unchanged.

"We united the Chinese market and market forces, and the results have been good. Your product can't be very competitive when you're not assimilated into the local market and society."

If local bosses have to check decisions with head office they've already lost, says Youku Tudou's Victor Koo

But Victor Koo, chief executive of video-sharing giant Youku Tudou, often dubbed China's YouTube, warns that having local managers on the ground isn't enough unless they are actually given genuine authority and can make decisions without having to check them with head office first.

"When you're an international company and you're trying to compete with a local company, if it means that every time you need to make a decision you need to go back to headquarters and then come back, especially in a space like ours, in the internet space. you're going to lose to your local competitor."

EBay's John Donahoe says succeeding globally can take up to 15 years

EBay chief executive John Donahoe, who wasn't at the helm during the firm's first foray into China, says the reality is it takes a very long time - somewhere between 10 and 15 years to establish a firm in new markets.

It now has 25 different domestic marketplaces globally which all use the same technology, but are run by local teams.

"We treat each market a little bit differently. They're all connected in a common technology platform, but balancing that local ownership, while also being part of a global technology platform, that's what we're trying to do," says Mr Donahoe.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.