Diesel cars: Is it time to switch to a cleaner fuel?

- Published

In the 1920s, pregnant women were encouraged to drink Guinness to increase their iron intake.

For decades we were all told to avoid fatty butter and eat synthetic margarine. Both pieces of health advice have since been discredited.

We are now learning that millions of motorists who've bought diesel cars believing they were less harmful to the environment have been equally misguided.

Diesel cars emit less carbon dioxide (CO2) than their petrol equivalent, we were told. In fact, not only are CO2 emissions almost identical on average, but they also produce large quantities of noxious pollutants linked with thousands of premature deaths.

Carmakers say they have already taken action to reduce emissions greatly, while regulators are beginning to acknowledge the problem, but the challenge remains enormous.

The reason is simple: about half of all cars currently sold in Europe are diesel powered.

As Greg Archer at Brussels-based think-tank Transport & Environment says: "The car industry is fighting to keep selling diesel because it has invested so heavily in the wrong technology".

Different reality

Air pollution caused by diesel engines is, for now, a peculiarly European problem. Of the 70 million cars sold worldwide last year, only 10 million were diesel. Three quarters of those were sold in Europe.

Quite why European carmakers developed diesel in the first place is a moot point, but some have argued, external that as domestic heating systems turned from oil to gas, oil companies needed to find an alternative market for their mid-range distillate, or diesel fuel.

The industry itself points to government incentives, such as lower tax rates for companies buying fleets of diesel vehicles. "All manufacturers followed this political direction," says the European Automobile Manufacturers Association.

The Audi A5 (l) meets EU nitrogen oxide limits, but the Audi A8 falls well short, one test found

And, in theory, it was an easy sell - diesel engines are more efficient than petrol engines, so running costs are cheaper. Using less fuel should mean lower emissions.

In practice, however, laboratory measurements of CO2 emissions from diesel and petrol engines are the same, according to Martin Adams at the European Environment Agency (EEA). And as diesel cars tend to be bigger and heavier, any advantages in efficiency are wiped out.

As a result, average CO2 emissions from diesel cars are only fractionally lower than those from petrol cars, figures from the UK's Society of Motor Manufacturers show. The industry counters that of course emissions would be greater from larger cars, and maintains that when comparing like-for-like models, diesels do emit noticeably less.

But carbon emissions aren't the main problem when comparing diesel with petrol. So-called particulate matter, which causes cancer, and nitrogen oxide and dioxide (NOx) are the real concern. Recent studies have shown, external that nitrogen dioxides (NO2) can cause or exacerbate a number of health conditions, such as inflammation of the lungs, which can trigger asthma and bronchitis, increased risk of heart attacks and strokes, and lower birth weight and smaller head circumference in babies.

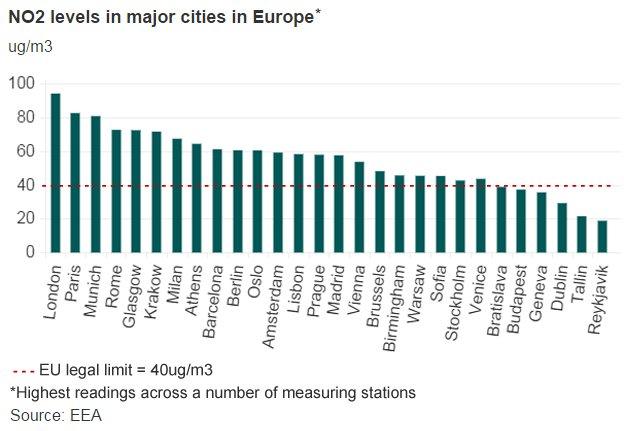

In some European cities, NO2 levels are more than double World Health Organization guidelines, with diesel vehicles the single biggest contributor, external.

Indeed air pollution as a whole causes more than 400,000 premature deaths, external in Europe, with road transport, and diesel in particular, contributing a meaningful chunk.

Inconsistencies

Most of these deaths are caused by particulate matter. Carmakers have recognised this and modern diesel cars are fitted with extremely effective filters that stop almost all of this carcinogenic soot entering the atmosphere. But there is a "significant problem with tampering with filters", according to Mr Archer.

Although a diesel car will fail its MOT if a filter that was originally fitted on the vehicle has been removed, there are a number of specialist companies which advertise doing just this for drivers who want to improve fuel economy and performance. Removing them isn't against the law.

So when you see a car belching out thick black smoke, the chances are it will be a diesel with a faulty or a missing filter.

These filters also perform best when hot, and short trips around town won't heat your engine sufficiently. Nor do they help with secondary particulate matter, which is formed from NOx, the effects of which are not fully understood.

How to reduce emissions from your diesel car

Don't accelerate unnecessarily

Get your car serviced regularly

Turn your engine off if you are stationary for more than one minute

Stick to the speed limits, especially on the motorway

Check your car's levels of urea (ammonia used to trap NOx)

Be very careful buying any retrofit solutions - none are fit for purpose according to Transport & Environment

Carmakers also have a number of technologies to reduce nitrogen oxide and dioxide levels. These include catalysts, re-circulating some of the exhaust fumes back into the cylinder, and injecting urea, made from ammonia, to trap these gases.

The problem is they are not being used widely enough and, when they are, they don't work as well as they should.

As the respected International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) says, "the technologies for real-world clean diesels already exist, but they are not being employed consistently by different [carmakers]". Some have speculated it's simply a question of cost.

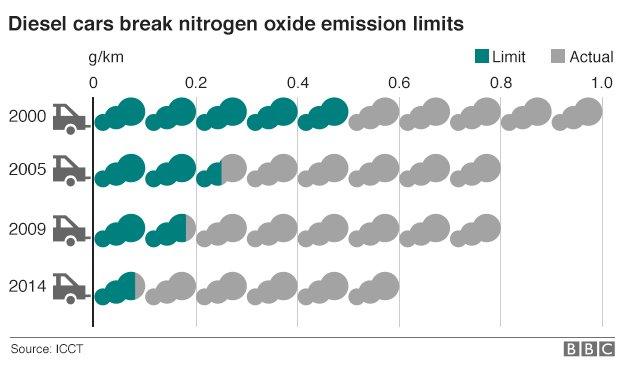

Just how ineffective they are is staggering. Tests conducted by the ICCT, external show that modern diesel cars emit on average seven times the EU limit for NOx.

A separate test showed that some individual cars emit even more - an Audi A8 emitted 22 times the limit. Only three cars - an Audi A5, a VW Golf and a BMW 3-series - complied with EU regulations.

'Meaningless'

The reason carmakers are allowed to keep selling these cars is that EU limits are set according to tests conducted in a laboratory, where conditions bear little relation to real-world driving out on the open road.

This extraordinary situation, which has effectively rendered current emission limits meaningless, has not escaped the attention of the EU. It wants to introduce limits based on real-world testing by 2017, but needs the agreement of all member states.

Carmakers agree real-world tests are needed, but would prefer more time. Discussions are ongoing, but the likelihood is that new limits will be higher than the current 80mg/km.

Given that this limit was first agreed in 2007, we may well end up with new limits for harmful diesel emissions that are less stringent than those agreed more than a decade earlier - an absurd situation that carmakers and policymakers must do more to address.