Airport expansion: It's build, build, build in much of the world

- Published

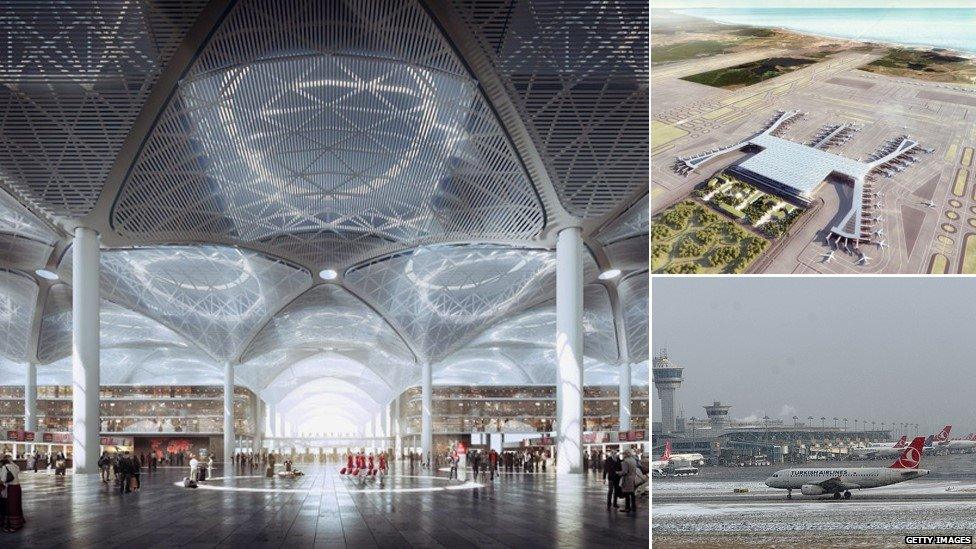

Radical departure: Designs for Istanbul's slick new airport, and its existing site (bottom, right)

A three-year review into the future of air travel around London is due to finish with the recommendation that a new runway be built at one of two existing airports. But while the capital gingerly edges towards airport expansion, other parts of the world are witnessing a massive airport building boom.

Along the Black Sea coast, 21 miles (35km) from Istanbul, an army of trucks and construction workers are labouring round the clock to build one of the world's biggest airports. The project was only announced two years ago by the Turkish government and yet it's due to open in 2018. Once fully complete, it will boast six runways and cater for 150 million passengers a year, travelling to 350 destinations. Or to put it another way, it will have more than twice the capacity of London Heathrow.

Never mind its size, the speed of this project alone is breath-taking. In the UK's South East region, on the other hand, it has taken several decades - and many official reports - to decide where to build a new runway. As the latest independent commission, external prepares to deliver its proposals, how are other countries managing the rise in air traffic, and is the growth in passengers really set to go on and on?

Read more

Temples of glass and steel

It's not just Turkey that's got its eyes on the prize of glittering glass and steel terminals. New shiny airports are in the pipeline in many of the world's growing cities. Mexico City is currently building the biggest airport in the Americas, designed by Norman Foster. Meanwhile, south of Beijing, construction is under way to build a new airport, Daxing, on an area of land the size of Bermuda.

Consultants KPMG has calculated 50 new runways will be built in the world's major cities by 2036. Seventeen of them will be in China alone. "These are not vanity projects," says James Stamp, KPMG's global head of aviation, "these countries know they need airports as part of their essential infrastructure to support their economic growth."

Air traffic keeps ascending

Ever since the beginning of aviation itself, air traffic has continued to grow. This upward curve has been amazingly resilient to external shocks over the years. Oil price spikes, the 9/11 attacks and SARS, a respiratory illness the spread of which was fuelled by air travel, may each have caused a temporary dent, but traffic always seems to pick up again. If you want to gaze into the crystal ball of aviation, perhaps the best place to look is the future order books of plane manufacturers - such as Boeing and Airbus. According to the policy wonks at Airbus, air traffic is going to double in the next 15 years.

Rising middle classes

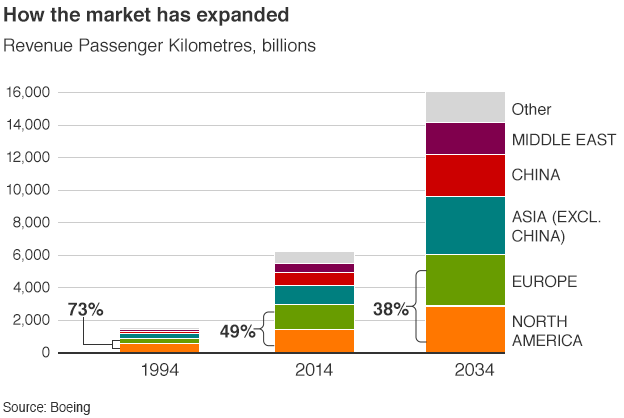

Both Boeing and Airbus believe that much of that increase will come from emerging economies, citing a direct link between air travel and economic prosperity. It will be fuelled by the rise of more affluent households especially in China and India. As Boeing's future market report puts it, "air travel is one of the first discretionary expenditures to be added as consumers join the global middle class." It's these demographics - and the global economy's shifting centre of gravity - which explain why the Asia Pacific region will become the largest air travel market in the world. In 1993, more than 73% of air traffic was carried by airlines in Europe or North America. By 2033, that will shrink to 38%, as the Asian and Middle Eastern carriers take centre stage.

Traffic moving eastwards

We've already seen how fast the global aviation market is changing with the rise of Dubai as a major hub airport - or "mega-hub". In 2008, the then chief executive of British Airways, Willie Walsh, warned Dubai would allow air traffic to bypass European hubs by providing a link between Asia and North America. Astoundingly, back then Dubai didn't even feature in league tables of the world's busiest airports.

It has now overtaken London Heathrow on international passenger numbers - ending Heathrow's decades-long dominance as the world's top international hub. Some aviation experts question whether hub airports are really the future. But Dubai is banking on yet more growth. Once its World Central Airport project is finished, it will boast more passenger capacity than all five of London's airports combined. Oxford Economics, the global research company, forecasts that by 2020, 37.5% of Dubai's GDP will come from the aviation sector and related industries.

The next Dubai

That's why others now want to emulate the Dubai model. Ethiopia is one of Africa's fastest growing economies and, because it sits on the edge of two regions, Africa and the Middle East, it's hoping to acquire a similar mega-hub status. The hunt is now under way for possible sites for a new airport which will handle 10 times the number of passengers that currently pass though Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa. The state-owned Ethiopian Airlines is already expanding its fleet in anticipation of this added capacity. That way, it hopes to copy the canny strategy of Emirates by providing more aircraft to fly to more destinations - growing in tandem with an expanding hub airport.

Inexorable rise?

No one really knows whether long-term aviation will continue growing as it has so far. Even those who are building the new generation of airports wonder aloud if the trend will hold. Dervilla Mitchell, an aviation expert from the engineering firm Arup, points to evolving new technologies. "Eventually," she says, "the tipping point will come when the virtual meeting is so effective it will reduce the need for business travel altogether." As emerging economies mature, they may also find more public resistance to airport expansion with environmental concerns rising to the surface. For the moment, though, UK business leaders look jealously at what's happening abroad, and wish Britain would get a move on with building its first full-length runway in the South East since World War Two.

- Published1 July 2015