Would Grexit have been a better deal?

- Published

Should Tsipras have thrown in the towel?

It will require Herculean efforts on all sides, including Greece.

That was the assessment of Mark Carney, the Bank of England governor, when he spoke about the agreement reached at the eurozone summit.

It's a widely shared view.

In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has criticised the bailout deal, saying Greece's public debt was now "highly unsustainable".

So would Greece have been better off throwing in the towel (perhaps one left behind by a German tourist)?

The drawbacks of signing up to the new proposed bailout are pretty stark.

First, more austerity. Greece's economy started contracting again in late 2014, having finally resumed growth earlier in the year.

Hitting targets for government borrowing - even easier ones than those included in the old bailout programme - will require measures that are bound to create a further headwind for the economy. Higher taxes and spending cuts will affect demand for goods and services.

There will also be a social price. Economic recovery prospects that are, at best, uncertain mean unemployment is likely to stay very high and living standards will not recover quickly.

There's also a political price, most immediately for the prime minister Alexis Tsipras. Already the unity of his Syriza party is fraying. It might mean another, early election. Do weary Greek citizens want to vote again so soon?

Handing over the reins

There's another political price; the loss of sovereignty. The economic policies that Greece is in the process of signing up to are driven by the creditors. They would argue that it's what's necessary to lay the long term foundations for economic growth and sustainable government finances. But those policies are certainly not what most Greeks thought they were voting for in the referendum or in the last election.

One of the prior actions required by the eurozone was to introduce "quasi-automatic spending cuts" if government finances deviate from targets. That's another inroad into the government's freedom of manoeuvre.

Greece has also had to agree to consult "the institutions" (the IMF, the European Central Bank and the European Commission) on all draft legislation in all "relevant areas".

Then there is the additional debt burden - likely to be about €86bn (£62bn). It is unlikely to be an immediate problem. The terms are to be negotiated, but they will involve a long repayment period. The final repayment of the second eurozone bailout loan isn't due until 2054.

But even before anything has been signed the IMF has lobbed a grenade, external into the debate with a warning that: "Greece's debt can now only be made sustainable through debt relief measures that go far beyond what Europe has been willing to consider so far".

The structural reforms will also be challenging. These are reforms to the labour market, to a range of markets for goods and services and to the regulation of various occupations. Many economists think they are highly beneficial in terms of the growth prospects they could unleash. But politically they will be tough.

There is also the potential for repeated episodes of banking restriction. Suppose that in the future, the European Central Bank worries - as it does now - about the financial viability of the Greek state and, as a consequence, about the solvency of the banks. The ECB might feel it has to restrict access to emergency loans, forcing the banks to curb customers' use of their accounts - again.

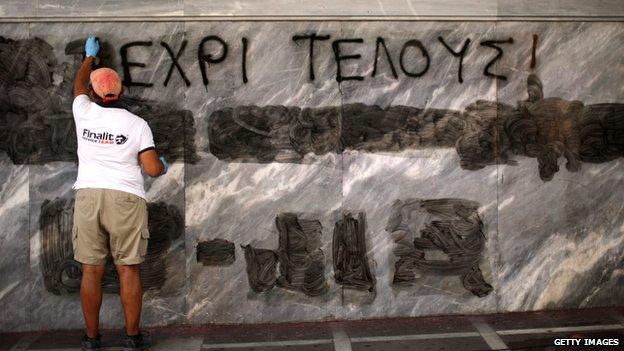

Tidy up time: Greece is trying to meet eurozone demands but it will be a Herculean task

So: plenty of reasons for Greeks to feel very uncheerful about the agreement with the eurozone.

Grexit gain?

The alternative would have been to decline the eurozone's kind offer of assistance and go it alone, outside the eurozone, and possibly outside the EU altogether.

That would mean a new (or perhaps the restoration of an old) currency. It would probably mean a fairly extensive default on the government's debts to the eurozone.

Sovereignty could be restored at a stroke. There would of course be constraints on the government's actions imposed by political and economic reality. But at least they would not have to seek permission from the eurozone.

There would still be a political price though. Voters want to stay with the euro. As Mr Tsipras has said: he has no mandate for leaving the eurozone.

What about the economics of departure?

There are widely divergent views.

The optimistic view is that it's exactly what Greece needs. It would, in this view, put right the two principal dangers involved in a currency union: the loss of an independent monetary policy and the loss of the exchange rate as a mechanism for adjusting to economic shocks. (Actually it's debateable to what extent they are really different things, but let's just park that question.)

Tempting the tourists

Greece with its own currency would be able to print as much as it wanted. Given that there's deflation, it might be helpful. It would also be necessary to refloat the banks.

The new currency would in all likelihood lose value against the euro, improving the country's competitiveness. Cheaper holidays might bring in the tourists in greater numbers.

But there is another view of how events might unfold and it's not pretty. A rapidly depreciating currency making imports more expensive could lead to rapidly accelerating inflation. Debts in foreign currency would become more onerous.

The introduction of a national currency would also be disruptive, with a chance of severe shortages of hard cash during a transitional period. Greece would not have the advantage of the long planning period that went with the introduction of the euro.

There is also a question about whether the government could finance its spending. Last year and the year before Greece had a "primary surplus" in the government's finances. That means if you take out interest payments, it spent less than it received in revenue. So you might think it could simply carry on spending. Well actually the primary surplus has now probably gone as the economy has weakened again which hits tax revenue.

So even if there were no further contraction in the economy, Greece with its own currency would probably either have to cut spending or borrow the money to finance a deficit - not an easy proposition if you have just defaulted, but some borrowing might be possible.

Crisis of confidence

There's also a question about whether EU spending - not bailout related - would continue. There is a legal view that leaving the euro is not compatible with staying in the EU. Perhaps a way of avoiding that would be found. If Greece did leave the EU, there might be humanitarian help from the EU, but the regular agricultural and regional spending would presumably stop. Total EU spending in Greece was 4% of national income in 2013, according to official European figures, external.

Eurozone exit would also create uncertainty and do some damage to consumer and business confidence, which might be severe.

So leaving the eurozone would undoubtedly have been possible and it is possible to see it as an opportunity. But it would have been a path fraught with uncertainty and a danger of some serious economic damage.