Sorry: Is it too hard for 'macho' company bosses to say?

- Published

It's taken the Japanese company Mitsubishi 70 years to apologise for using American prisoners of war as slave labour during the Second World War. And it has been hailed as a landmark, the first Japanese company to do so.

Why do companies find it so hard to say sorry?

Thomas Cook: Holiday tragedy

Former Thomas Cook chief executive Harriet Green avoided making an apology for two years

In 2006, two children, Bobby and Christi Shepherd, were killed by carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty boiler in a hotel on Corfu while on a Thomas Cook holiday.

But the company would not apologise.

"The Thomas Cook [example] was terrible," says Kate Betts, a specialist in crisis management at Capital B Media.

"Their argument might have been 'it wasn't us, it was the hotel', but to the public it looked like it was Thomas Cook and they needed to stand up and just take it on the chin."

The company may have been trying to avoid an admission of liability.

"I think companies listen too much to the lawyers," says Betts. "Really they should be thinking about their reputation because the cost in reputational damage may end up be more than the cost of any compensation anyway."

Eventually, a new chief executive, Peter Fankhauser, came round to that way of thinking and issued a sincere apology.

You do not run the risk of litigation by apologising, according to Jeff Helmreich, assistant professor of philosophy and law at the University of California Irvine, as long as you are careful about the wording.

"You've got to walk a tightrope. You can't say an apology that suggests nothing self-critical: for example 'I feel bad about what happened to you'. That's an ineffective apology," he says.

"Apologies can simply convey: we would like - and wish we could make up for what we did, but we can't. It doesn't necessarily admit we were at fault."

"However, from a practical point of view it's wiser not to contain factual statements about what one did."

BP: Belated apology

Tony Hayward's mistake was to hesitate.

As news came in on 20 April 2010 he faced the appalling prospect of BP becoming, for a time at least, the most loathed company in America.

BP's chief executive Tony Hayward was fiercely criticised by the US media

The only chance he had was to express his immediate, heartfelt regret. But he fluffed it.

"They did say sorry, but it took them a little while because they were trying to decide who was responsible," says Magnus Carter, reputational management advisor at Mentor Ltd. "Because the rig was owned by another company and operated by a third company."

"It was only a matter of hours... but in the digital age apologies have to be immediate or they lose their impact."

That delay may have cost them a great deal of political goodwill, as the belated apology came across as less sincere than an immediate one would have.

And a more elaborate video apology, external later was deemed by some to be an example of self-serving, "humble-bragging" as, as well as saying sorry, it spelt out all the effort BP was putting into the clean up.

Hugo Boss: Nazi past

Many German companies used forced labour during the Nazi era

German companies were a bit quicker off the mark to express contrition than their Japanese counterparts.

Still it took German fashion firm Hugo Boss until 2011 to apologise for its links with the Nazis during the Second World War.

But at least then the company offered its "profound regret to those who suffered harm or hardship" at its factory, which used forced labour.

Mr Boss's firm had made uniforms for the SS among others and was just one of a number of German companies including Bosch, Daimler, Deutsche Bank, Mercedes and Volkswagen that used forced labour during the Third Reich.

Fifty-five years after the Reich collapsed, in 2000, the German government and 6,000 German firms set up a €5.1bn ($5.5bn; £3.5bn) fund to compensate surviving victims of the Nazi era.

The experts agree: taking action to compensate victims is one of the sincerest forms of apology.

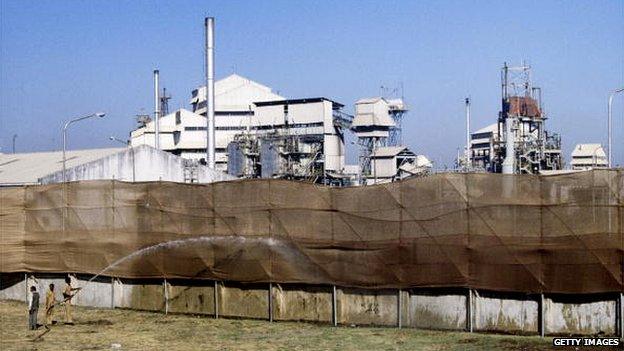

The Bhopal gas leak remains one of the world's worst industrial disasters

Union Carbide: Bhopal gas disaster

In 1984, a leak of poisonous gas from a pesticide factory in the Indian city of Bhopal killed more than 3,000 people and left an estimated 40,000 maimed or injured.

The cause of the disaster is still debated. The Indian government and local activists say that a lack of proper maintenance at the plant helped trigger the disaster. But Union Carbide, the US chemicals firm that owned the factory, has always denied negligence. It agreed to an out-of-court settlement of $470m in 1989 and was taken over by Dow Chemical.

Survivors of the Bhopal disaster and activists taking part in a protest march in New Delhi

An apology was suddenly forthcoming on the 20th anniversary of the accident. Unfortunately it turned out to be a hoax, external.

Prof Helmreich thinks the company could easily have apologised without opening itself up to litigation.

"Every study shows that when a corporation apologises they're much less likely to be sued, to be protested, to be opposed in various ways.

"Apologising… tends to mollify people and end conflict."

But he admits the kind of people who get to the top of a major corporation aren't usually the types to put themselves in a position where they're conceding the moral high ground, even when it makes business sense.

"Corporation leaders have the same human instinct that prevents people from apologising: simply the desire not to subordinate and indebt oneself to someone else.... That's a reversal of respect and certain hierarchies that people find very difficult even when there's no legal cost."

News of the World: 'Serious wrongdoing'

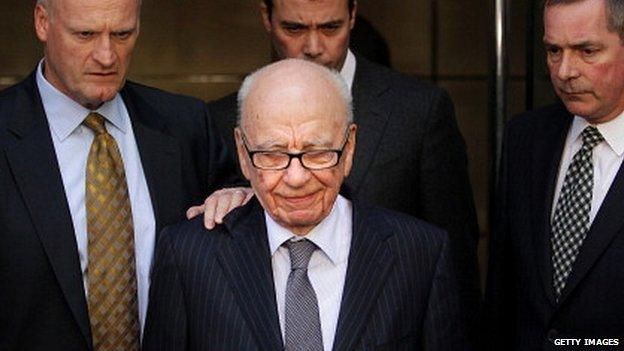

Rupert Murdoch's apology after the discovery that journalists at the News of the World had been hacking the phone of murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler is perhaps the most thorough expression of corporate regret on record.

A signed apology from Rupert Murdoch admitted to "serious wrongdoing" by the News of the World. At that point the media magnate had much to lose by not showing contrition.

But reputation manager Magnus Carter says these kind of apologies are hard to extract from seasoned business leaders.

"Saying sorry is quite an emotional thing to do.

"In the corporate world it's quite a macho culture - facts, action, authority are [considered] more important than emotional responses.

"The reality is the opposite: people have an emotional response and that's what you need to address."

News Corp's chairman Rupert Murdoch after meeting the family of murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler

Carter suggests if you want to tread carefully around admitting responsibility there are alternative ways of expressing it.

"There are other words you can use. Regret is one. It's a weasel word; I'd never advise a client to use it.

"If you don't feel sorry you can say you're concerned, or deeply upset to hear what's happened."

If you can bring yourself to say it, it really is worth the effort, Carter says: "I tell clients all the time to say sorry - we all just know it's so powerful."

- Published19 July 2015