Facing the future at the International Monetary Fund

- Published

Maybe it has been the strange twists and turns of the Greek financial crisis that have brought the anomalies of who it is that runs the IMF into sharper focus - whatever the reason the Fund's leaders certainly seem concerned.

"Our governance needs to be fully modernised to reflect an ever-changing world," said David Lipton, the IMF's first deputy managing director - spelling out the problem facing the organisation as he sees it.

"If you're China or a fast-growing country, you need to know that there'll be a series of changes that enable your role at the IMF to grow," he told the BBC World Service's In the Balance programme.

Since being set up in 1944 at the Bretton Woods Conference along with the World Bank, the IMF has played a critical and at times controversial role in stabilising the global economy.

It has intervened in national economies with huge loans and often a highly prescriptive set of loan conditions as it did in the 1997 and 1998 East Asian crisis, in Africa throughout the last three decades and most recently in the eurozone in Ireland in 2010, in Portugal in 2011 - and of course, now in Greece.

Many in Greece have objected to the terms of the IMF's loans to their country

IMF loan agreements usually require severe cut-backs in government spending - austerity with a capital 'A' - tax reform, pensions reforms and a crackdown on corruption. The Fund rarely leaves a country with more friends than it had when it arrived.

But recently there has the increasingly noisy criticism of the IMF's pecking order. For many outside the Fund there is the nagging question which comes along with its loans and the calls for countries to reform their economies: "Says who?"

'An incredible anachronism'

Under the rules agreed when the IMF was established, every IMF managing director must be a European. Currently it is Christine Lagarde - and in fact five of the 11 IMF's leaders have been French. Meanwhile, the head of the World Bank must be an American, say those same rules.

So when unpopular measures are demanded by the IMF in exchange for funding for a country, there is a sense that the West, the world's richer economies, the ones that have been calling the shots for the last 70 years and are seemingly willing to ignore the rapidly shifting global economic landscape - are still calling the shots.

Harvard University's Prof Kenneth Rogoff, and formerly chief economist at the IMF said: "The number one issue for the IMF, is to dispense with the ridiculous requirement that the managing director be a European, and that the World Bank be run by an American."

Critics say the 1944 rules on who should head the IMF have to change

"It's an incredible anachronism."

Prof Ngaire Woods, an expert in global governance and dean of the Blavatnik school of government, Oxford University, goes further: "I think the risk to the IMF is irrelevance and marginalisation."

"Emerging economies are using other things - anything but rely on the IMF. If you're sitting in Zambia, Brazil or China, it looks like an organisation that's still run by the USA and Europe."

Rival institutions

Last year, saw the arrival of the New Development Bank - now known as the Brics Bank - whose members include Brazil, Russia, Indian, China and South Africa and whose stated aim is to foster greater financial and development cooperation along the emerging market countries.

Its offer is remarkably similar the that of the World Bank, but for a smaller audience and without the history.

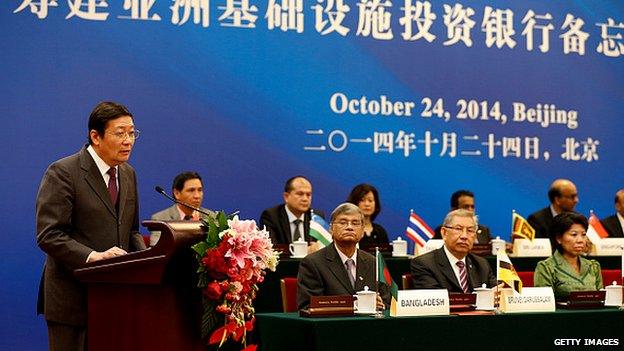

And there is also the prospect now of the new China-backed AIIB or Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which again will offer global development funding.

As the AIIB project has been pushed through, driven by Beijing's ambition and the raw spending power, the United States has pleaded with fellow Western economies to reject it: and it has had to stand by and watch as one by one they have approached the AIIB with open arms - including German, France and the UK.

The US may not have joined the AIIB, but many other countries have

The Bank now has 56 prospective founding members, a roll call of the world's biggest economies, with the notable exception of the US.

Perhaps the IMF is now also unsettled by the willingness of the Germans, French and Brits to participate, and thus the possibility that new organisations may to eclipse its global role, and that of the World Bank.

Wider selection

So it could be with that in mind that the IMF's David Lipton was so clear in his expression of the need for change when talking to In the Balance: "I don't think that people have given up on us, but I do think that there is a threat that they will."

Christine Lagarde could be the last European to head the IMF for some time

The Greek response to the stiff terms of the IMF's crisis loan, serves as a reminder that governments under pressure from their electorates, might start to choose to go elsewhere to borrow if alternatives are on offer.

David Lipton says he is confident that the next selection for head of the IMF will be strictly based on merit, with candidates coming from around the world.

For Sargon Nissan of the Bretton Woods Project, and a long-time critic of the IMF, this claim is pivotal: "We've been waiting for 20 years to hear this - it is very significant."

Yet, when asked if IMF staff ever regretted their role in the Greek financial crisis, David Lipton is equally clear: "Pardon me the US baseball metaphor, but when you go to bat you have to hit the pitch that's thrown at you. It's our job; and we take it with pride."

It will be interesting to see where their ball lands.

You can find this week's episode of In the Balance, along with the programme podcasts here.