Did technology kill the book or give it new life?

- Published

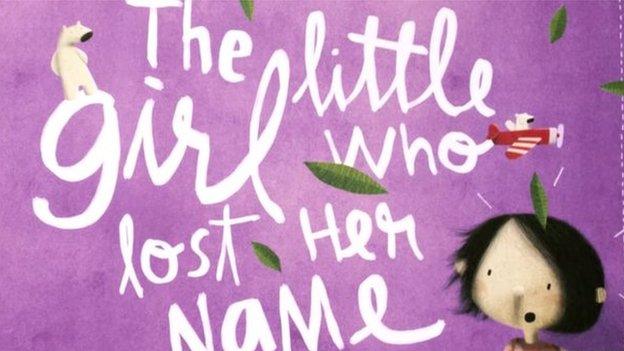

The picture book that you can personalise online became a bestseller

The book is dead, long live the book.

Digital technology has certainly had a profound effect on the traditional book publishing and retailing industries, but has it also given the book a new lease of life?

At one point it looked as if the rise of e-books at knock-down prices and e-readers like Amazon's Kindle and Barnes & Noble's Nook posed an existential threat to book publishers and sellers.

"Literature found itself at war with the internet," as Jim Hinks, digital editor of Comma Press, succinctly puts it.

But contrary to expectations, the printed book is still surviving alongside its upstart e-book cousin, and technology is helping publishers and retailers reach new audiences and find new ways to tell stories.

Print fights back?

While there can be no denying that printed book sales have taken a massive hit with the rise of digital, there is some evidence that the rate of decline is slowing and that the excitement over e-readers is subsiding.

Kindle sales - peaking at 13.44 million in 2011 - fell back to 9.7 million in 2012 and have plateaued since. Barnes & Noble's Nook e-reader has been losing about $70m (£45m) a year and the US bookseller has been trying - and failing - to find a buyer for the division.

The rise of the e-book

30%

share of UK book purchases

-

47% share of adult fiction

-

£393m spent on e-books

-

£1.7bn amount spent on print books

In the UK, roughly £1.7bn was spent on print books last year, compared with £393m on e-books, says Nielsen Book Research's Scott Morton. The digital newcomers' share of the market seems to have settled at about 30%.

On the high street, Waterstones saw physical book sales grow 5% over the Christmas period compared with the year before, while Foyles saw sales rise 8.1%.

The era of the printed book, it would seem, is far from over. But a lot depends on the sector you're looking at.

Adult fiction - particularly romantic and erotic - has migrated strongly to the e-book, whereas cookery and religious books still do well in print, as do books with illustrations. All for fairly obvious reasons.

Does format matter?

There are plenty of services out there trying to bridge the gap between the physical and the digital, extending the definition of what a book is.

Lostmyname's books bridge the gap between the physical and the digital

In 2014, a personalised publishing experiment won the largest equity deal ever on the BBC Dragons' Den TV programme.

The Little Girl Who Lost Her Name - a printed book that could be digitally individualised to include the name of the child reading it - went on to be the top-selling children's picture book in Britain and Australia.

Spanish company SeeBook offers e-books as physical cards that can be bought online or in bookshops like other gift cards. Simply scan the QR code in the card with your smartphone or tablet to download the book.

"Some book stores still see digital as the big monster that's going to eat them, and prefer to put their head into the sand," says SeeBook director Dr Rosa Sala Rose.

SeeBook is trying to bridge the gap between the physical and the digital

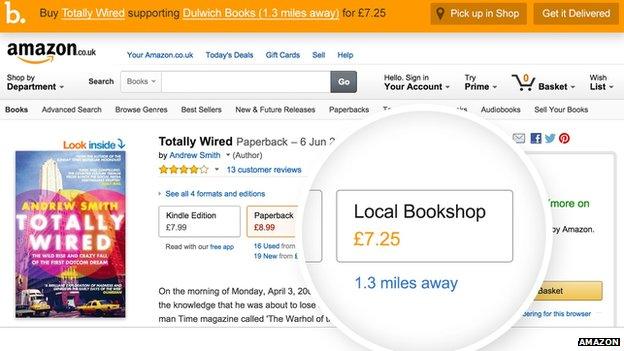

London-based tech start-up Bookindy is using technology to encourage people back to struggling local bookshops.

It does this with a Chrome browser plug-in - each time you search Amazon for a book, a window pops up saying how much it would cost at your nearest independent bookseller.

Founder William Cookson, who describes himself as "just an average sort of book reader", says his creation took just three days to code.

It helped that he could tap in to an existing network of 350 independent British bookshops called Hive, which enables retailers to check stock and fulfil orders.

Bookindy aims to being people back to local bookshops by highlighting that Amazon isn't always cheaper

Serial revival

Digital is also reviving some centuries-old publishing ideas, says Anna Rafferty, until recently head of Penguin Books Digital.

Just as Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers was published in instalments in 1836, so Serial, a prizewinning US murder story, was podcast last year in 12 episodes, to great acclaim.

"Digital technology and the rise in the digital reading culture has allowed authors and publishers many more new creative opportunities to develop 'the book' further and delight readers," she says.

"It also allows authors to publish directly, to connect intimately with their readers and, crucially, to create new ways of telling their stories."

The Pigeonhole - launched in October by former Random House employee Anna Jean Hughes and partner Jacob Cockcroft - serialises books and enables readers to share comments and interact with the authors, all via an app. It's like a digital book club.

Anna Rafferty, former head of Penguin Digital, reads a print book to her boys at bedtime

In a similar vein, Manchester-based MacGuffin from Comma Press acts like a Spotify for books - you can hear authors reading their stories out loud. Its analytics reveal what gets read where, and at what point people lose interest.

Readers can append tags to a story - "sci fi", "dystopian", or "feminist", for example - and use these to discover other new fiction, much in the same way someone might browse through a physical bookshop.

Digital distraction

Competition from mobile devices is one reason for Kindle sales levelling off.

"With mobile phones, screens are so much bigger, and the experience not as garish as it used to be," says Mr Hinks.

But although smartphones are convenient - you can buy and download a book in seconds - they can also be very distracting, posing an added challenge to e-book sellers.

Books on electronic devices "compete with games, news, and social media, and so need to be slicker," says Laura Summers, co-founder of BookMachine, a popular publishing networking website.

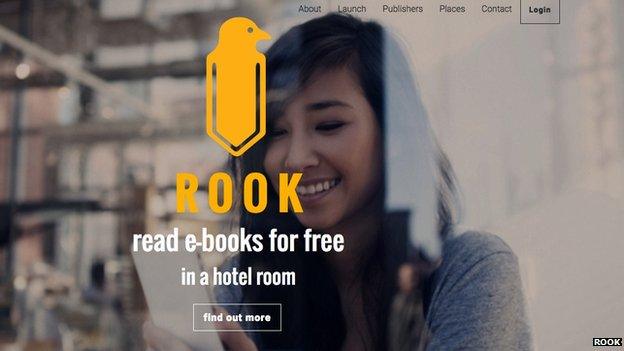

Rook is providing access to free e-books at selected wi-fi hotspots

To hook people into reading, another start-up, Rook, is offering access to free e-books at wi-fi hotspots, such as London Underground stations, participating coffee shops and retailers.

"By the time they have to leave and go off about their life", says co-founder Curtis Moran, "they'll be so hooked into the book they're going to have to buy it."

He compares his start-up to a traditional bookshop, where you can sit and read for as long as you wish, but have to pay if you want to take the book with you.

So the book isn't dead; technology is simply helping it evolve beyond its physical confines.

Long live the book.