The architects using animation skills to build film careers

- Published

"It's very important to see the space through the lens," says architect Angelika Vasileiou

In a warehouse in north London, I'm surrounded by hundreds of painstakingly made card models and framed architectural plans, all meticulously presented.

There are also dozens of other-worldly 3D-printed structures, some of which seem to resemble buildings.

This much you might expect at the annual Bartlett School of Architecture degree show.

But held aloft above them in a corner, is a monitor playing a haunting film - an animated journey through a labyrinth - with a dramatic voiceover.

Why is an architect making a film like this?

It turns out that architecture students, who can spend five-figure sums on their seven-year training courses, are using their newly-learned digital animation and design skills to break into the world of film.

Angelika Vasileiou learned how to make complex animations in two years

The film's creator, Angelika Vasileiou, explains the appeal of animation.

"I've never been so close to designing a space, realising how it feels, before I started making films," she says.

She looks exhausted as the show comes to a close. Her mind is on what to do after graduation.

"There are many possibilities for architects to work in film," she says. "It's exciting, we have the skills. A lot of students are considering film."

'Natural progression'

Ms Vasileiou is a product of Unit 24 at The Bartlett.

The unit, explains tutor Penelope Haralambidou, explores the relationship between architecture and film.

The Bartlett School of Architecture graduate show is open to the public

"Ever since architects began to draw digitally, a crossover with film has been a natural progression," she says.

On the one hand, this is practical. Architecture firms need to make animation films to dazzle prospective clients. And of course they use 3D software to originate designs and make plans for engineers and builders to follow for construction.

But Unit 24 encourages students to go beyond this.

In many ways the unit's output resembles that of a film school, at times more David Lynch than Sir Norman Foster.

The films encourage imaginative thinking and project management skills, says Bartlett tutor Simon Kennedy. And they also teach students the fundamental principles of design, he emphasises.

Student Kelvin Ip's degree film imagines Hong Kong as a citadel in 2047

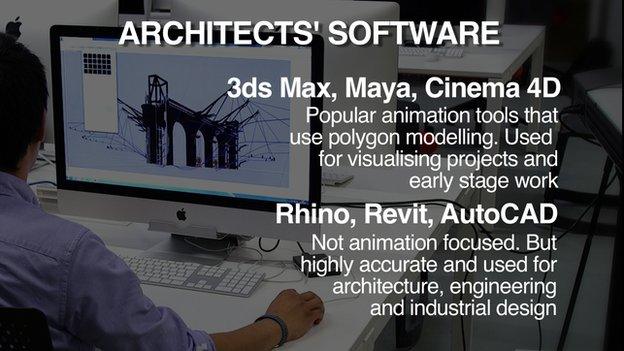

Most students arrive with no animation skills, but within two years are up to speed. They use animation modelling software like 3ds Max, Maya and After Effects.

The same software is also used in the visual effects (VFX) industry for film.

"Architects tend to have a vivid imagination and a strong visual sensibility," says Mr Kennedy.

"But this is tempered by their capacity for analysis and problem solving. These characteristics are directly applicable when first designing digital animations, and then executing them effectively."

Alumni of the school have already capitalised on this skills crossover. A group who graduated in 2011 has formed Factory Fifteen, an animation house. Recent projects include animations for Film4 and a visualisation of the Al Rayyan football stadium, external, made for the press launch of the Qatar 2022 World Cup.

Factory Fifteen made an animated film of the Qatar 2022 World Cup Al Rayyan football stadium

There is also ScanLab, which specialises in recreating dramatic 3D environments. Their work includes the D-Day landings, external for PBS in the United States and classical Rome for the BBC.

The switch

But is it really that easy to build a film career from architectural foundations?

One man thinks so. Ben West is creative director at Framestore in Los Angeles.

Framestore is a London-based VFX company employing more than 1,000 people that has won Oscars for films such as Gravity.

After graduating in architecture in Sydney in the late 1990s, Mr West combined regular architecture work with a sideline in his true passion - film and animation.

This passion culminated in the award-winning short film Fugu & Tako, external - a buddy movie with a twist. Two Japanese salarymen's lives are transformed forever, when one of them eats a live puffer fish in a sushi bar, with surreal VFX-laden consequences.

Former architect Ben West made the award-winning animated short film, Fugu & Tako

"The reality, apart from a few extremely talented individuals, is that architecture has become very utilitarian in its focus," says Mr West.

"I aspired to more creative pursuits and my talents were better suited to film making, so I have no regrets."

With Framestore he has directed effects on Beyonce videos and Super Bowl half time shows.

Mastering the software was the easy part for an architect, says Mr West.

"Good architecture strives to relate to the human condition and tell a story, so, too, do good filmmakers.

The mantra at architecture school was always 'form follows function', now it's more about the picture serving the story."

Building bridges

So why are architects moving into film?

"Undoubtedly this is because both professions make use of similar software products," says Adrian Dobson, an executive director at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

"During the recent recession turnover for UK architectural practices overall fell by more than a third and it was a difficult time for younger architects seeking to establish their careers in architecture, so flexibility in how they applied their skills was a must.

Framestore worked on the visual special effects in the Paddington film

"It is probably more ad hoc than a trend, but it is a reasonably well-trodden path."

From the employer's point of view, architects "understand the structure of real-world built environments," says Amy Smith, Framestore's head of recruitment.

"They also bring a knowledge of the history of architecture and how certain features reflect the time or culture of buildings.

"All of these things bring a sense of believability to a computer-generated environment that allows an audience to engage with the story."

Fresh blood

But others have found the transition into film animation more difficult.

Han Han Xue, a new recruit to Framestore in Montreal, graduated in architecture in 2014 from McGill University. He taught himself animation online.

Even fantasy spaces must be believable, like this scene from the Guardians of the Galaxy film

"I would produce things which would baffle teachers, but are elementary in the film world," he says.

But he admits that "the skills required are much, much higher than what a highly competent architect would be able to offer."

And he doesn't rule out returning to architecture and using his enhanced film animation skills to create amazing buildings, he says.

Digital, it seems, has helped build a two-way street between architecture and film.

Follow Dougal Shaw, external and Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall, external on Twitter.