'Foolish to pre-announce' rate rise date - BoE's Broadbent

- Published

The Bank of England's deputy governor for monetary policy has told the BBC it would be "foolish to pre-announce" a date for an interest rate increase.

On Thursday, the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee voted to keep interest rates at their current historic low of 0.5%.

Deputy governor Ben Broadbent said the Committee had no specific time in mind for a rise and comments by governor Mark Carney had been misinterpreted.

The cost of borrowing has remained unchanged for 78 months.

The ultra-low interest rate regime has boosted the housing market as homeowners enjoy record low mortgages rates, but penalised savers whose returns have dwindled to almost nothing.

Speaking to Radio 5 live's Wake up to Money programme, Mr Broadbent said: "We [the MPC] are responding to things that are essentially... unpredictable.

"And that means that it would not just be impossible, it would be foolish to pre-announce some fixed date of interest rate changes."

Mr Broadbent said he saw no "urgency" to increase interest rates at present.

He added: "The economy clearly is recovering, but we had the most almighty financial crisis and there is still a bit of spare capacity left.

"There is not that much inflationary pressure at the moment, [although] we expect that to build over time."

Speaking later on Radio 4's Today programme, Mr Broadbent said the recent fall in the price of oil had "delayed any rebound in inflation until early or spring next year".

'Cockroaches'

Chris Williamson, chief economist at research group Markit, told the Today programme that more members of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) could vote to raise rates in the coming months. On Thursday, meeting notes revealed that only one member voted for a rise this month.

He said that it takes "a long time for interest rates to feed through, so policymakers need to look two years ahead. Pick up in wage growth means we could see 2% inflation in two years, and the longer you leave raising rates, they higher they will have to go [in order to keep inflation in check]".

Also speaking on the Today programme, Merryn Somerset Webb, editor-in-chief of MoneyWeek, said that despite the Bank's prediction that rates would rise slowly, no-one knew what the future held, so mortgage holders should at least be prepared for the possibility that rates could rise faster than they might think.

"As one fund manager said recently, interest rate rises are like cockroaches - they tend to come along in groups," she said.

Record lows

The Consumer Prices Index, the most commonly used measure of inflation, fell to 0% in June, while earlier this week, the cost of a barrel of crude oil fell below $50, its lowest point since April.

Despite problems in the wider global economy, caused by the continuing crisis in Greece and fall in Chinese stock prices, Mr Broadbent said the overall outlook for the UK remained steady.

"We've seen unemployment come down pretty steeply," he said, "and some signs of improving productivity growth. We've seen a material pick-up in wage growth, not sufficient to give us any big inflationary risk.

"But all of that would naturally lead to the case for some normalisation of interest rates to start building."

He added that the economic recovery looked "well embedded and solid", with the Bank expecting "steady growth over the next two years".

'Process of adjustment'

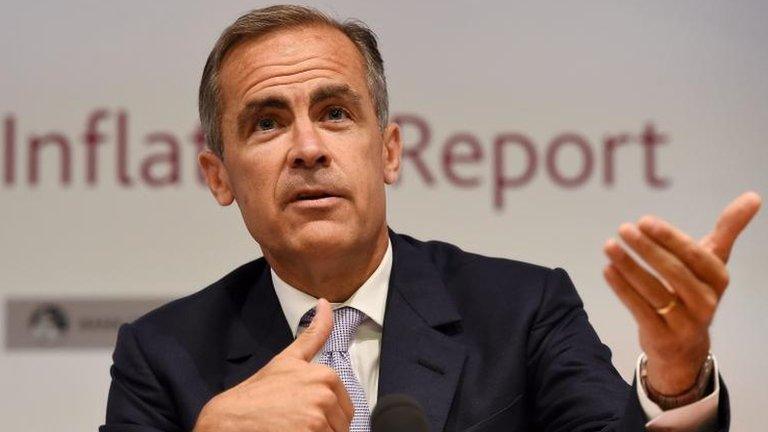

Mr Broadbent was responding to media coverage of remarks made last month by the Bank's governor, Mark Carney.

In a speech at Lincoln Cathedral, Mr Carney gave what was interpreted as his clearest hint yet that the cost of borrowing would go up before 2016.

He said: "The decision as to when to start such a process of adjustment will probably come into sharper relief around the turn of this year."

- Published6 August 2015

- Published6 August 2015

- Published16 July 2015