Would Corbyn's 'QE for people' float or sink Britain?

- Published

- comments

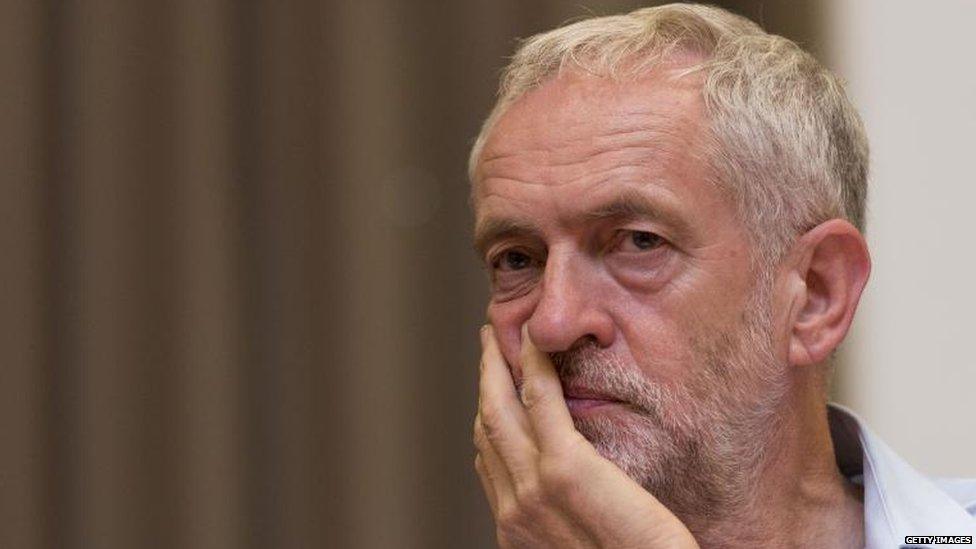

Bookmakers have installed Jeremy Corbyn as favourite in the leadership race

So what are the economic policies of the long-serving Labour backbencher, Jeremy Corbyn, who has become the darling of Labour's new members and - out of nowhere - has become favourite to emerge as leader of Her Majesty's Opposition?

Helpfully he produced an economic manifesto, "The Economy in 2020".

At its heart is the precept that "Labour must create a balanced economy that ensures workers and government share fairly in the wealth creation process, that encourages and supports innovation in every sector of the economy; and that invests in skills and infrastructure to build an economy that is more sustainable and more equal".

Which is the sort of statement, absent detail on the means to get there, that most would say sounds alright.

But Corbyn is, famously, of the left. So his path to creating a more sustainable and equal society would not appeal to all.

Even so his opposition to this government's planned cuts to corporation and inheritance tax, and his muscular hatred of tax avoidance and evasion, are not the stuff of swivel-eyed Leninism.

There are plenty of political moderates who question why, at a time of scarce resources, it is a priority for messrs Cameron and Osborne to give tax breaks to better-off dead people.

But of course that is not the end of Corbynism. Like many left-wingers of his generation, he never felt comfortable with privatisations and was not persuaded by his erstwhile leader, Tony Blair, that Labour was right to end its Clause 4 commitment to pursuing public ownership of the means of production.

So Jeremy Corbyn wants the state to re-acquire ownership of the railways (as does another left-ish candidate to lead Labour, the lapsed Blairite, Andy Burnham), he has floated a plan for the government to acquire controlling stakes in energy companies and he has talked about whether Labour should adopt a new modern version of the traditional socialist commitment for the workers to own the towering heights of the economy.

Some of you of a free-market inclination may at this juncture be spluttering into your flat whites and mojitos. But again, there is nothing desperately surprising about any of this.

The hard left didn't die under Tony Blair's aegis. It was marginalised. A bit like punk rock in the reign of the Spice Girls, it retreated into specialist clubs and cabals, knowing that one day there would be a hunger for its seductive remedies for the world's injustices.

So the underlying causes of the ascent of Corbynism are driving politics throughout the rich west - and benefit the extreme populist right (the Front National in France, Trump in the US) as much as the Syrizas and Podemoses of the left.

They include a palpable sense that the establishment parties have for years and consistently lied about the benefits of globalisation, given the inescapable evidence that disproportionate spoils go to the very rich.

And almost everywhere tolerance of an economic model that appeared to disempower all of us, and whose fruits were not available to all, dramatically decreased after the 2008 Crash that turned lacklustre wage growth into sharply squeezed living standards.

Liz Kendall, Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Jeremy Corbyn hope to succeed Ed Miliband

So Corbynism is a kind of collective howl - which can be heard in different accents all over the world - that it doesn't have to be this way.

But what is driving mainstream Labour members bonkers about all of this is the way that Corbyn's supporters - some young and new to the party, others freshly returned from self-imposed exile in other far left caucuses - are wearing their support for Jeremy Corbyn as a badge of protest, the equivalent of a ripped punk-rock t-shirt, but not as part of any practical collective mission to form a Cabinet and actually govern.

And, by the way, what is particularly galling for what you might call conventional Labour is how Ed Miliband's party reforms priced the T-shirt at just £3 - which is all you have to pay to have a vote on Labour's next leader.

In this context, Jeremy Corbyn's most important policy is actually his most novel. And it is what he calls, alluringly, "quantitative easing for people instead of banks".

This is how he describes it: "one option would be for the Bank of England to be given a new mandate to upgrade our economy to invest in new large scale housing, energy, transport and digital projects".

For the avoidance of doubt, this is not same-old, same-old socialism; it is new, radical thinking.

But in a world where globalisation and the free movement of capital are inescapable realities, so-called quantitative easing for people brings considerable risks. Some will see it as stupendously dangerous.

For detail on what it involves, Jeremy Corbyn prays in aid the campaigning tax analyst, Richard Murphy.

Now here it gets a bit technical so bear with me.

What we think of as normal quantitative easing - though it was unconventional when the Bank of England embarked on it in 2009 - involves the Bank of England creating new money to buy government debt.

There is a lively debate about quite how economically useful it has been. It might have pushed down interest rates a bit for all, through a slightly convoluted transmission mechanism. And it might have encouraged a bit of incremental consumption and investment by inflating the price of houses and other assets.

But probably the most important point about quantitative easing as currently configured is that the debt bought by the Bank of England has to be repaid - eventually - by the Treasury.

In other words the £375bn of new money created by the Bank of England through quantitative easing will one day be withdrawn from the economy, through the repayment of debts by the government, when the economy is perceived to be strong enough.

Now it will be decades before all the £375bn is returned. And theoretically it could never be repaid, if the Bank of England simply decided to roll over maturing debts each time they are due for repayment (as it is doing at the moment).

But the important fact is that the debts still exist as a real liability of the Treasury - and that matters.

Here is why.

Central banks, like the Bank of England, have an extraordinary privilege and power to magic money out of nowhere. Which is another way of saying that money has no intrinsic value, and is only worth what we as a society determine it is worth. And, in the reality of global financial capitalism, it is currency traders who decide what sterling is worth, nano-second by nano-second.

So to avoid a collapse in the currency and rampant inflation, central banks have to be seen to be exercising great restraint in the creation of new money.

The lore of central banks - which, rightly or wrongly, is almost universally accepted by investors - says that central banks should only look at whether there is too much or too little money in the economy in determining whether to increase or shrink the supply of money, and not at narrower economic questions such as whether there are enough roads or houses being being built in Britain.

Or to put it another way, successful central banks are those that are not bossed around by politicians, who are perceived to be more interested in being re-elected than in economic stability.

Would Jeremy Corbyn's policies threaten the Bank of England's independence?

Now to be clear, none of this is to argue that Jeremy Corbyn is wrong to want more investment in energy, housing and other infrastructure. But it is to say that if the Bank of England were mandated to do that, most investors would conclude that the Bank of England's primary objective was no longer to preserve the value of the currency but to finance politically popular projects.

They would fear that if the Bank of England is forced to finance projects that the private sector - by Jeremy Corbyn's admission - won't finance, it would be throwing good money after bad.

In those circumstances, sterling would weaken, with inflationary consequences - and perhaps with devastatingly inflationary consequences.

Probably Jeremy Corbyn and his counsellor Richard Murphy would argue that this is unduly alarmist - and that all the Bank of England would be doing would be to purchase new debt issued by energy or transport companies, presumably state-owned or state-backed, and this is surely not much different from the Bank of England's purchases of gilts or government debt.

That may be right, as a matter of theory, and even - in the case of America - in practice, in that the Federal Reserve in the US has subsidised housing finance for years by purchasing colossal amounts of state-backed mortgage debt.

What is more the former head of the Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, has been arguing that in order to make meaningful inroads into the UK's massive debt burden, the Bank of England should consider going one step further than quantitative easing and - in a highly prescribed way - create money to actually annul debts.

But the dollar is still the world's reserve currency, and the Fed can take liberties with it that are not available to the Bank of England.

Also it is very difficult to conceive of a way in which the perception - the confidence trick perhaps - of Bank of England independence could be preserved, while obliging it (to repeat Jeremy Corbyn's words) "to invest in new large scale housing, energy, transport and digital projects".

Once it had those explicit objectives, investors would see it as politician's poodle and conclude that preserving the value of sterling would be not quite the priority it has today.

Which is not that the UK would turn into hyperinflationary Zimbabwe or 1923 Germany.

But the risk of investing in sterling and the UK would be seen to have increased. And therefore the cost of finance here would rise - which would mean that there would be even less long-term productive investment here, and a British malaise correctly identified by Jeremy Corbyn would be made more acute.

UPDATE 16:05

The guru of Corbynomics. Richard Murphy, has responded, external to my blog on Jeremy Corbyn's "quantitative easing for people".

He clarifies that the debt to be acquired by the Bank of England would be issued by a new state-owned investment bank, whose role would be to finance housing, transport, and so on.

But I am not sure the existence of this new public-sector bank significantly helps his cause.

Because there would be widespread concerns that the Bank of England would be indirectly financing white elephants via this investment bank - and would, as I mentioned earlier, be throwing good money after bad.

Or to put it another way, quantitative easing for people makes good economic sense only if you believe that a state investment bank would make viable investments that the private sector refuses to make.