The bio-fuel start-up that sells cooking gas by the rucksack

- Published

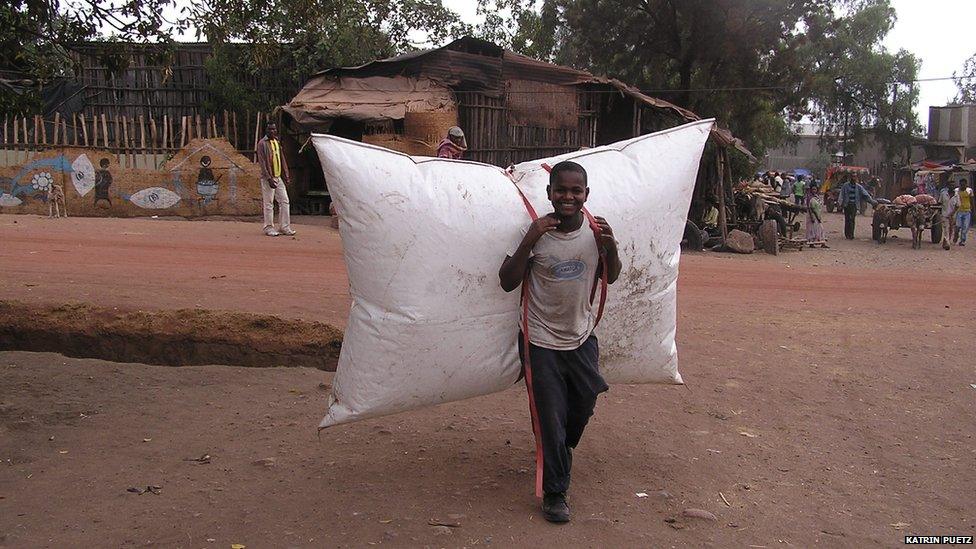

B-Energy has developed balloon rucksacks to allow people to deliver its biogas

Inside a large ramshackle shed a struck match is held to the end of a metal pipe, and a faint blue flame springs into life.

Zenebech Alemayehu smiles, puts her finger tips to her lips, then towards the flame, a symbolic kiss for her new biogas business.

A single mother with a nine-year-old son to look after, Ms Zenebech, 32, recently bought a local franchise from a company called B-Energy, which aims to provide households across Ethiopia with cheap, portable biogas for cooking.

The metal pipe leading into Ms Zenebech's shed comes from a 5m (16ft) long plastic tank, which is a sealed compost bag or "digester".

You add food waste or animal droppings to the bag, and it produces methane gas which can then be piped out.

To fuel her digester in a southern suburb of Ethiopia's capital Addis Ababa, Ms Zenebech collects cow dung for free from a nearby dairy farm.

When enough gas is produced, she transfers it into two metre-long, pillow-shaped inflatable balloons, which can be carried on your back like a rucksack.

Zenebech Alemayehu previously made a living washing clothes and as a cleaner

Currently Ms Zenebech is using the biogas to cook snacks to sell at the police station next door, but her longer term aim is to sell the bags of gas to nearby homes, along the lines of the business model suggested by B-Energy.

Each balloon backpack holds 1.2 cubic metres of gas, enough for about five hours of cooking. Ms Zenebech plans to sell them for 10 Ethiopian birr (50 cents; 31 pence).

The heat and fire resistant bags come with a tap and pipe, which users simply attach to their gas stove.

When the balloon bag - which remains the property of B-Energy - is exhausted, users return it to their nearest franchisee for it to be refilled with gas.

Ms Zenebech says of her digester: "When I see it working I am so happy."

Cleaner alternative

B-Energy is the brainchild of German entrepreneur Katrin Puetz, 34.

With a masters in agricultural engineering, Ms Puetz began the project while working for Hohenheim University in Stuttgart.

The sealed compost bag or digester produces methane gas from animal droppings and food waste

Realising its potential in Africa, as a clean, cheap alternative to cooking on smoky, polluting wood fires, she contacted Addis Ababa University, which invited her to move to Ethiopia for a year, and helped her develop the technology.

So in April of last year Ms Puetz launched B-Energy in the east African nation.

Although she was offered grants from global charities, she says she turned them down because she wanted to show that B-Energy could stand on its own feet.

The digesters are typically covered with a tent to raise their temperatures

"My aim is not to just provide biogas, but to show it can be provided without aid," she says.

"This is not just about money, it is about pride - why do we always have to have aid and subsidies for something that can work on its own?"

As the business is still in an infant state it currently only has two franchisees in Ethiopia and one in Sudan.

Ms Puetz says that she has yet to determine how much money franchisees will need to pay to buy for their first digester and bags when the business is fully up and running.

However, she estimates a price of between 400 euros ($441; £281) and 800 euros, varying from country to country.

The balloons are light enough for children to carry them on their backs

Meanwhile, extra empty gas bags will each cost 43.50 euros.

For a country like Ethiopia these are high prices, but Ms Puetz says she is wants franchisees to be able to pay in instalments, and she is in talks with finance providers.

While it is hoped that franchisees like Ms Zenebech will make a profit on their part of the business, B-Energy itself is being run as a social enterprise, with profits reinvested into the business.

Araya Asfaw from Addis Ababa University's sustainable development agency, the Horn of Africa Regional Environment Centre and Network (HOAREC), helped with the development of B-Energy.

He adds that it is essential that franchises are not given anything for free.

"When you give something for free, people do not value it, it may end up under the bed," he says.

"But make them pay and they then want the training, and use it properly."

'Too bulky'

To help promote B-Energy after its launch last year, the company came up with a novel idea in the town of Arsi Negele, 200km (124 miles) south of Addis Ababa.

Yodit Balcha, who owns the national B-Energy franchise for Ethiopia as a whole, explains: "Rather than just tell people, we connected a digester to a local cafe so people could see how it worked.

Katrin Puetz (left) is in talks for B-Energy to be part of Ethiopia's National Biogas Program

"The technology is easy and simple, which helps acceptability."

Within weeks Ms Yodit says 26 households were buying B-Energy's gas sacks.

Yet despite B-Energy's optimism and enthusiasm, biogas is nothing new in Ethiopia and across Africa as a whole.

In fact in Ethiopia a government-backed scheme called the National Biogas Program is already rolling out biogas production across the country, and is funded by millions of euros from a Dutch charity.

B-Energy says its novel difference is its inflatable bags, which make the biogas far more portable, and therefore much easier for people to buy and sell. It is in talks to join the National Biogas Program.

However as Mr Araya admits, the large size of the bags may make them unsuitable for some cramped urban settings.

He says: "In the rural areas you have plenty of room, but it will be harder in the cities. The system is too bulky."

Despite such concerns about the size of the bags, Ms Zenebech is not deterred.

Having previously worked washing clothes and cleaning buildings, she is determined to be her own boss as she pushes ahead a fledgling business plan.

Up to her elbow in slurry as she mixes cow dung with water to add to her digester, she says: "I have done harder labour than this."