China's slowdown and cheap oil

- Published

China's economic slowdown has finally left its imprint on global stock markets. But the impact has been discernible in the oil market for many months and it has gone further in the last few days.

The reason: China is the world's biggest importer of crude oil.

It took top spot in April this year, external and even before that was behind only the United Sates.

Slower economic growth in China means less demand for oil than there would otherwise have been.

Of course there are other factors behind the oil price collapse of the last year, some of them leading to abundant supplies. The rise of shale oil in the United States and Saudi Arabia's unwillingness to respond by curbing its own output have also put pressure on the oil price.

But demand is an important element.

And just look at what the impact of all these factors has been.

The price of Brent crude oil roughly halved in the second six months of last year. It recovered a bit and then fell by nearly 40% from the level it reached at about the same time (in June) that the Chinese stock market began its sharp decline.

That's not to say the Chinese stock market is directly responsible for oil's fall. But it has reinforced concerns about whether China's economic growth is going to slow very abruptly, and has undermined expectations about future oil sales - driving down the price now.

Oil revenue dependency

Cheaper oil is a great boon for struggling economies that have to import the stuff. There are plenty of them around, notably the eurozone.

But it is an increasingly serious problem, certainly economically and perhaps politically too, for oil-exporting countries.

Oil accounts for a very large share of government revenue in many countries. The IMF says, external it's more than half for many oil exporters and as high as 80-90% in some, including Iraq, Qatar, Oman and Equatorial Guinea.

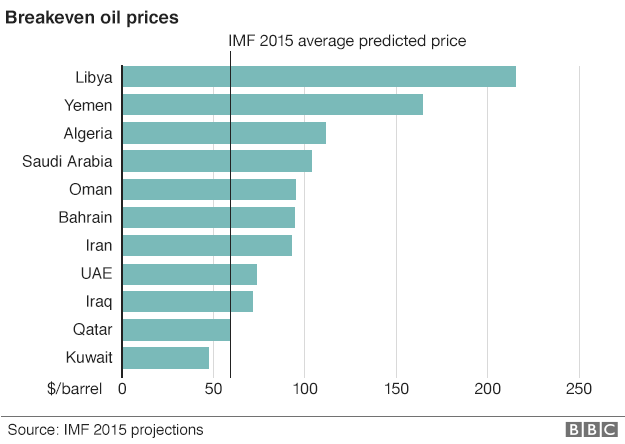

The IMF has also estimated, external the oil price it would take for some countries in the Middle East and North Africa (and a couple in the former Soviet Union) to balance their government budgets. For all of them that "breakeven" price is higher than today's level.

For several, including Saudi Arabia and Iran it would take a lot more than double what it is now to balance the budget. For Libya it is more than $200 a barrel, higher than the oil price has ever been.

Economists at Deutsche Bank have done a similar analysis, external and extended it to a few more countries. They suggest that Venezuela and Nigeria would also need an oil price of about $120 a barrel to balance the books.

The IMF is forecasting a deficit in the Saudi government finances of 14% of national income this year. Saudi Arabia has reserves it can draw on, savings built up in years of higher oil prices. The same is true of some other oil producers, but such a low oil price would be a problem even for these countries if it were to persist for several years.

Some, Nigeria for example, have much thinner financial cushions.

Social contract

These economic strains could have a political impact.

Bahrain is one of several Middle East countries that is heavily dependent on oil

The state has had a central role in the economic life of many countries across the Middle East and North Africa. It has been called a social contract.

The World Bank said, external: "The old development model - or social contract - where the state provided free health and education, subsidized food and fuel, and jobs in the public sector, has reached its limits."

This social contract is not confined to the oil producers, though an earlier World Bank report, external said that oil is important to other countries in the region as migrant workers get jobs in the sector and send funds home.

The limits on this social contract were a key factor behind the political turmoil known as the Arab Spring. And many of the big oil exporters in the region are relatively authoritarian political regimes.

Rising living standards and public services funded by oil revenue play an important part in the political balance in countries such as Saudi Arabia.

There are strains which came into the open in some countries with the Arab Spring and which are present across the region. None are really immune, certainly not Saudi Arabia. Those problems could easily be aggravated if the oil business were to cease to provide the resources it has in the past.

Venezuelan inflation

Among the major oil producers Iraq has a very serious domestic issue to contend with - the insurgency of the group calling itself Islamic State. It is an expensive business and lower oil revenues will make it all the more challenging.

Venezuela is another stark case. It has the world's largest oil reserves, although a large part is in the form of very heavy oil that is expensive to refine. The country had acute economic problems even before the oil price drop.

Venezuela has the world's highest inflation

The government's finances have been in deficit to the tune of more than 10% of national income or GDP since 2010, and this year the IMF has forecast a figure of 20%. The IMF is also forecasting an economic contraction of 7% and inflation of more than 1,000% - that means prices increasing more than tenfold in a year.

The former finance minister, now Harvard Professor, Ricardo Hausmann wrote almost a year ago, external:

"All of this chaos is the consequence of a massive fiscal deficit that is being financed by out-of-control money creation, financial repression, and mounting defaults - despite a budget windfall from $100-a-barrel oil."

Since he wrote, oil prices have crashed and the implications for the government's budget are painfully clear. There have been protests against President Nicolas Maduro, in what has been called, external "a deepening political crisis… leading to civil violence and potential regional instability".

Russia is another big oil producer, which has reserves to draw on. It too has an inflation and economic contraction problem, though not on Venezuela's scale. A key factor there has been the low oil price driving down the value of the rouble which makes imports more expensive.

Iran is a rather different story. Of course a high price for oil exports would be helpful. But the government is hoping for rapid increases in the volume of oil sales if, as it expects, the western sanctions are lifted following the deal on the country's nuclear programme.

In fact the resumption of more normal levels of Iranian exports would exacerbate the weakness of the oil price, assuming the market doesn't turn a corner in the meantime. But for Iran, the priority is to regain lost market share.

It is what you would expect from any government in that situation, but it is likely to be yet another headache for the world's other oil exporters.