India - we can take the economic lead as China stumbles

- Published

- comments

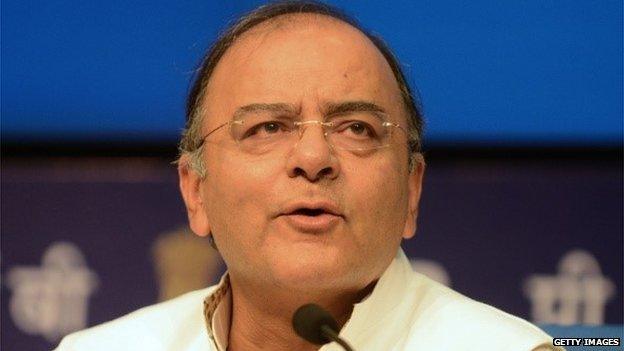

Democracy is "one of India's greatest strengths", Finance Minister Arun Jaitley tells Kamal Ahmed

Nothing better sums up the contradictions of India than the main road south-east from Delhi to the city of Agra.

Running alongside this major arterial route as it snakes out of the capital is the new Delhi metro - something akin to the London Underground (though a lot smaller).

Although city residents complain that it is already horribly overcrowded just over a decade after the first line opened, it is nevertheless an enormous show of infrastructure muscle.

Every year millions of commuters travel to and from the city on its six new lines and so avoid the daily gamble of Delhi's notorious traffic jams.

And, as any management consultant will tell you, better transport links can add to a country's economic prosperity.

Alongside the shiny metro line, the main road to Agra is a rather dowdy affair.

Within a few kilometres it rollercoasts its way from slick toll road to passable motorway to rough dual-carriageway to pot-holed and rubble-strewn track.

There is, of course, the obligatory wandering ox to negotiate every now and again.

Fast, fast, slow, slow. India's economy in physical form.

Jitters?

It is an economy in need of reform and Prime Minister Narendra Modi insists he is the man to do it.

And with China stumbling and global markets concerned that one Asian engine of growth could be in for a hard landing, can India, now growing faster than China, pick up the reins?

Frankly, does it have the muscle to calm world economic jitters?

Mr Modi will undertake an official visit to Britain in the autumn to sell the "Indian dream".

I am told that he quite fancies hiring Wembley Stadium for an event celebrating the generations of Indian immigrants who have made the UK their home.

If it goes ahead, it will be similar to Mr Modi's glitzy appearance at Madison Square Garden in New York during his 2014 US visit.

Stadium events aside, many argue that - if Mr Modi gets the reforms right - the country he leads could economically dominate the next two decades in the way that China's growth story has dominated the last two.

Elected last year by a landslide by millions of Indians tired of decades of talk and not enough action, Mr Modi said it was time for a step change in the pace of growth.

Bogged down

Stifling bureaucracy, infrastructure projects trapped in endless rows over who, precisely, owns which bits of land, a parliament wracked by political in-fighting and a tax system baffling in its complexity are just some of the problems the country faces.

Just over a year after that heady election, the complaints have started - that Mr Modi is not moving quickly enough, that promises remain just that - promises - and that grand plans for land reform and tax changes are bogged down in parliament or even going backwards.

The last session of parliament - appropriately called the monsoon session (it rains a lot in Delhi in August) - passed precisely zero pieces of reform legislation despite Mr Modi's efforts.

One commentator, Gurcharan Das, the former head of Procter & Gamble in India, said that the country was still a "hostile place to do business".

And if that is true, essential foreign investment will never flow.

Foreign investment?

I spoke to the finance minister, Arun Jaitley, one of Mr Modi's most powerful allies, and asked him for his response to critics who say the government has disappointed.

"The government has absolute clarity about the direction it has to pursue," he said. "Prime Minister Modi's government almost by the day is continuing to move and reform in the right direction and slowly but surely the results are showing."

Banking has been reformed to allow more private sector involvement. The defence sector, insurance and real estate have similarly been opened up. Some bureaucratic procedures have been simplified and "ease of doing business", Mr Jaitley insists, is improving.

He admits, though, that much change is still "work in progress" and that India's infrastructure is still "a far cry" from the ideal.

To encourage in much needed external finance, Mr Jaitley says he will be "laying out the red carpet" for foreign investors.

Many eyes are now turning to India as China wobbles. Did Mr Jaitley fear that India could be swept up in the global gloom that has struck this week, another emerging economy facing tougher times?

"It had a transient impact," Mr Jaitley said of China's stock market turbulence and the decision to allow the renminbi to devalue.

"For instance, when the Chinese economy slowed down a little it had not much impact. When the devaluation and the currency war started we did get somewhat adversely affected. When global markets fell [on Black Monday earlier this week] so we also felt a huge impact in terms of currency and markets.

"But within a day we had recovered.

"I see this as a great opportunity. The Chinese 'normal' has now changed. It is no longer the 9%, 10%, 11% growth rate.

"So the world needs other engines to carry the growth process. And in a slow down environment in the world, an economy which can grow at 8-9% like India certainly has viable shoulders to provide the support to the global economy."

'Opportunity'

The head of JCB in India told me that as a net importer of oil and other commodities India was now in a "sweet spot".

As emerging economies such as Brazil and Russia struggle, reliant as their economies are on commodity exports, India is gaining from the deflationary cycle.

"For us, lower commodity prices and lower oil prices are a boom,'' Mr Jaitley said.

"It is an opportunity and a challenge to Indian politics - if we can continue to reform at a faster pace and really attract global investment, then our ability to provide that shoulder which the world economy needs will be much greater.

Mr Jaitley said that the Indian government had already gained a windfall from lower oil prices because it had reduced the need for public subsidies to consumers. That money, he said, was now going to be invested in infrastructure development.

India's growth story matters, because, according to Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, India has the potential to become the third largest economy in the world in the next decade.

At present it is ninth.

With a population of 1.2bn, a figure which is growing more rapidly than China, some estimate that the country will have the largest number of middle class people in the world by 2020.

And the higher the number of middle classes people, the higher the level of consumption, which means opportunities for exporters from Britain and around the world.

"The flourishing middle classes creates huge opportunities," Ambarish Mitra, an Indian businessman who launched his technology business, Blippar, in the UK and is now exporting it back to India, told me.

"The purchasing power of that middle class is growing. Many people are not going outside of India anymore because so many global companies are setting up shop in India.

"Overall the consumption cycle which makes an economy richer, all the factors are in place [for India]. That is great news for the business community."

History

And, even if the government struggles to complete infrastructure projects or reform tax laws, the growth of mobile technology can start doing some of the heavy lifting.

"It is one of the single biggest factors [in the development of the economy]," Mr Mitra said.

"True empowerment and distribution of knowledge in this day and age comes from connectivity, and connectivity was an issue for the last decade. Now 3G and 4G connectivity is rapidly changing that landscape."

4G, he said, was now in over 200 cities across India.

It is often said that India lives in several centuries at once. The hyper-modern mobile network, the Victorian era railways and of course the cattle in the street, a reminder of India's rural past.

Economic growth has sometimes been an uneasy bedfellow to India's history and its loud and often aggressive politics.

Mr Modi and Mr Jaitley know they need consensus if they are to lead a government that can harness the country's remarkable history, rather than fight it.

And they could also do with completing that motorway from Delhi to Agra, or at least filling in some of the pot-holes.