Migrant crisis: Business in 'The Jungle'

- Published

With thousands of migrants living cheek by jowl in a makeshift camp on the edge of Calais, a ramshackle infrastructure of shops, restaurants, schools and entertainment venues has emerged to meet their daily needs. The BBC's Howard Johnson met some of the enterprising individuals who have started businesses in "The Jungle".

A patchwork grey sky stretches above the sprawl of migrant tents and shelters. It's been raining all week and the effect is etched on residents' faces. But inside the Afghan Flag Cafe, the mood is anything but dour.

A look at some of the businesses that have been started in The Jungle

Three Afghan men chat and laugh as they puff on a shisha water pipe. Occasionally they call over to two Eritrean girls, nervously giggling as they eat a plate of rice and vegetables.

In the other corner of the rectangular tent, a wok filled with oil and chicken pops and crackles. The warmth from the stove provides welcome respite from the wet and cold outside.

An aid worker from the French Christian charity Secours Catholique drops in for a cup of sweet chai. Manning the kitchen is 47-year-old Sikander from the Nuristan province of Afghanistan.

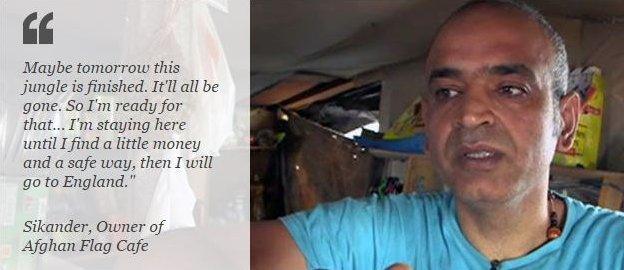

Maybe tomorrow this jungle is finished. It'll all be gone. So I'm ready for that... I'm staying here until I find a little money and a safe way, then I will go to England."

He fled war in his country in 2007 hoping to claim asylum in the UK. Since then he's lived in Italy, Norway and France. He moved to the camp in Calais in June this year.

Shortly after he arrived, he tried and twice failed to smuggle himself into Britain. Realising the danger of breaking into lorries, Sikander decided to open the first restaurant in the camp.

"Better to do something than nothing," Sikander tells me, as he chops and peels onions. "I started with just potatoes and bread. Being the first business was too good. With more than 3,000 people in the camp, there was no place for people to sit. "

With three business partners, Sikander works round the clock to feed up to 100 people a day.

"We are working here 17 to 18 hours. When I wake up I start working, until I sleep I'm working," he says.

Sikander beams as he says that on a good day he can earn anything up to 50 euros (£37). But where there's success, imitation quickly follows:

"Other people saw it and said 'oh this restaurant is working here' so now there are lots more restaurants but we still have customers because our food is better than others'. The customers say that."

Tour of the Jungle

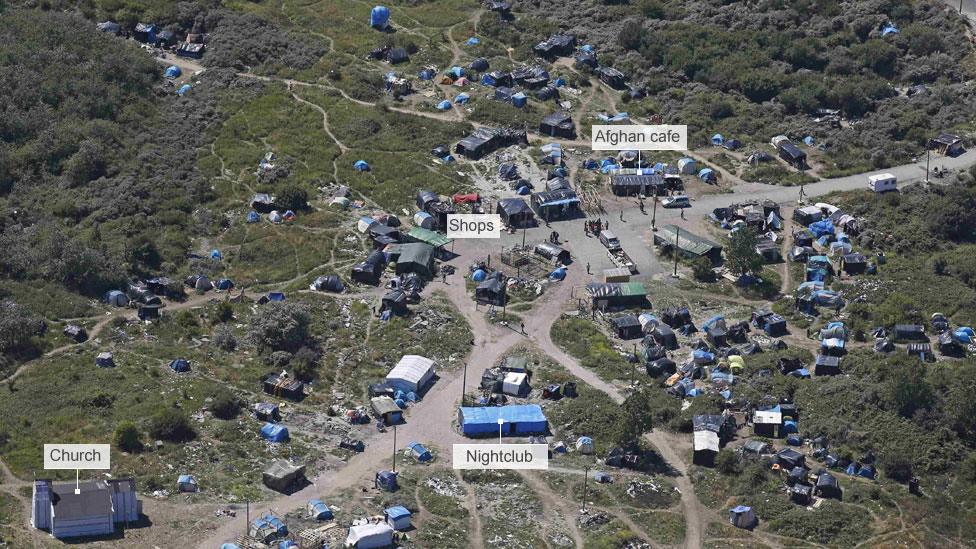

A walk around the camp reveals that there are now more than 20 other shops and restaurants in operation. They offer an alternative to the food handouts from visiting charities and the Jules Ferry Day Centre next to the camp - both of which attract long queues.

A quick tour of Calais migrant camp, where businesses are popping up among the shacks and tents

Shops in shacks and tents have sprung up around the main arteries of the camp. The site is now even more crowded than shown in this aerial image from July

The vast majority are Afghan-run convenience stores. They're dotted along a bumpy winding road that bisects the camp.

Some people have started to call this area "The Market".

Most of the shops offer similar products: fizzy drinks, mobile top-up cards, toothpaste, soap and vegetable oil.

Talking to shop owners, they tell me they buy their goods from supermarkets in Calais and then wheel them back to the camp in shopping trolleys.

Clubbing together

One store has green wire mesh in the window to deter would-be thieves. Inside, three Afghan men huddle around a tub of tobacco and a cigarette-rolling machine.

The lever is wrenched and a perfectly-formed cigarette drops to the ground. The sticks are then bundled together in handfuls of 10 and wrapped in tinfoil.

Each packet sells for a euro. The workers tell me that a container of tobacco makes around 50 euros' profit.

The convenience stores along the main routes through the camp are mainly run by Afghan migrants

Some shop keepers take precautions to protect their goods

Machine-rolling cigarettes turns a profit for some migrants in the camp

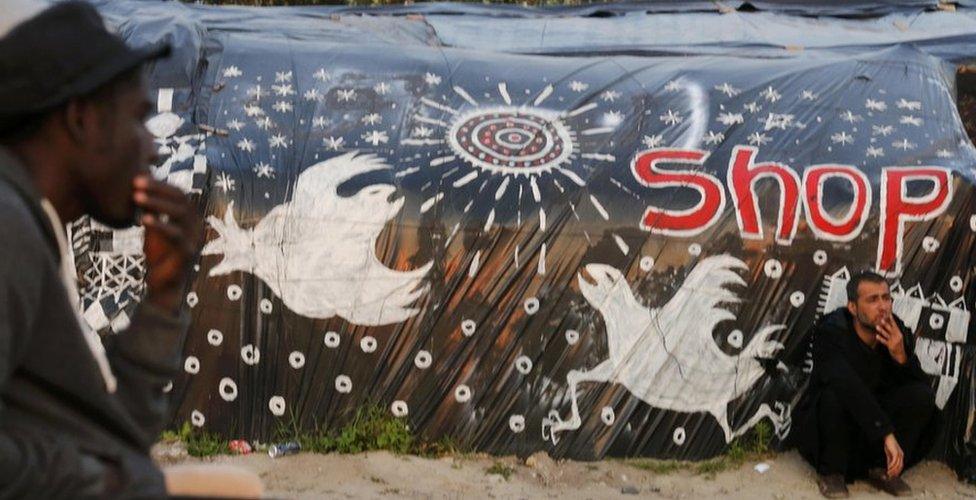

Outside the shop, a throbbing beat pulsates down the street. It's coming from the camp's nightclub, a business run by a group of men from Eritrea.

Inside the long rectangular tent sit groups of Eritrean and Sudanese men engaged in animated conversation. There's not much in the way of decoration, just a large space in the centre of the tent for dancing.

In a partitioned area a couple of women are busily preparing food and drinks. A can of beer here will set you back €1.50. It's strong stuff: 7.9% alcoholic content.

Plans to leave

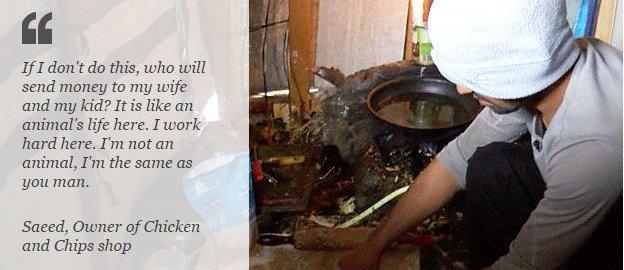

Next to the club is the "Chicken and Chips Shop".

The chicken and chips shop is popular with neighbouring nightclub customers

Saeed, the Afghan owner, says he does well by selling food to inebriated club-goers.

"This club is open 24 hours," Saeed says, as he rolls an Afghan Bolani bread. "Dancing, beats, every time there is fighting. At 3am it's 'give me this one, give me this one.'"

Saeed left Afghanistan in 2008. In the same year, he illegally smuggled himself from Calais to the UK . But in 2010 he was caught by police and sent back to France. He's been living in the country for the last five years. He says he tried to get back to England more than a hundred times.

If I don't do this, who will send money to my wife and my kid? It is like an animal's life here. I work hard here. I'm not an animal, I'm the same as you man.

So why did Saeed decide to open the shop?

"If I don't do this, who will send money to my wife and my kid?" he replies. "It is like an animal's life here. I work hard here. I'm not an animal, I'm the same as you man."

Before I leave the camp, I visit Sikander once more. I ask him if he feels any conflict in running a business in the camp while at the same time having ambitions to leave Calais?

"No, no, no, I'll still go to the UK," he replies. "Maybe tomorrow this jungle is finished. It'll all be gone. So I'm ready for that. If I can work in 'The Jungle' and I can start a business in 'The Jungle', if I'm in the city and I work then I will do it better than here because I don't have a lot of facilities.

"I'm staying here until I find a little money and a safe way and then I will go to England."