Computers 'do not improve' pupil results, says OECD

- Published

- comments

Sean Coughlan reports: The OECD study has raised ''doubts'' about the positive impact of technology on school learning

Investing heavily in school computers and classroom technology does not improve pupils' performance, says a global study from the OECD.

The think tank says frequent use of computers in schools is more likely to be associated with lower results.

The OECD's education director Andreas Schleicher says school technology had raised "too many false hopes".

Tom Bennett, the government's expert on pupil behaviour, said teachers had been "dazzled" by school computers.

The report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development examines the impact of school technology on international test results, such as the Pisa tests taken in more than 70 countries and tests measuring digital skills.

It says education systems which have invested heavily in information and communications technology have seen "no noticeable improvement" in Pisa test results for reading, mathematics or science.

Unplugged

"If you look at the best-performing education systems, such as those in East Asia, they've been very cautious about using technology in their classrooms," said Mr Schleicher.

"Those students who use tablets and computers very often tend to do worse than those who use them moderately."

Annual global spending on educational technology in schools has been valued at £17.5bn, by technology analysts Gartner. In the UK, the spending on technology in schools is £900m.

The British Educational Suppliers Association (BESA) says schools have £619m in budgets for ICT, with £95m spent on software and digital content.

But Mr Schleicher says the "impact on student performance is mixed at best".

Students who use computers very frequently at school get worse results

Students who use computers moderately at school, such as once or twice a week, have "somewhat better learning outcomes" than students who use computers rarely

The results show "no appreciable improvements" in reading, mathematics or science in the countries that had invested heavily in information technology

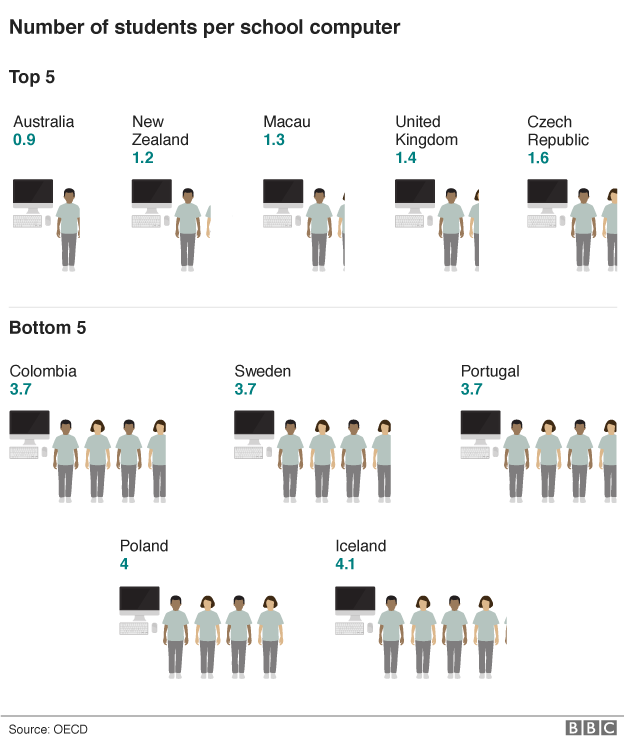

High achieving school systems such as South Korea and Shanghai in China have lower levels of computer use in school

Singapore, with only a moderate use of technology in school, is top for digital skills

"One of the most disappointing findings of the report is that the socio-economic divide between students is not narrowed by technology, perhaps even amplified," said Mr Schleicher.

Andreas Schleicher has warned about students copying their homework from the internet

He said making sure all children have a good grasp of reading and maths is a more effective way to close the gap than "access to hi-tech devices"

He warned classroom technology can be a distraction and result in pupils cutting and pasting "prefabricated" homework answers from the internet.

The study shows "there is no single country in which the internet is used frequently at school by a majority of students and where students' performance improved".

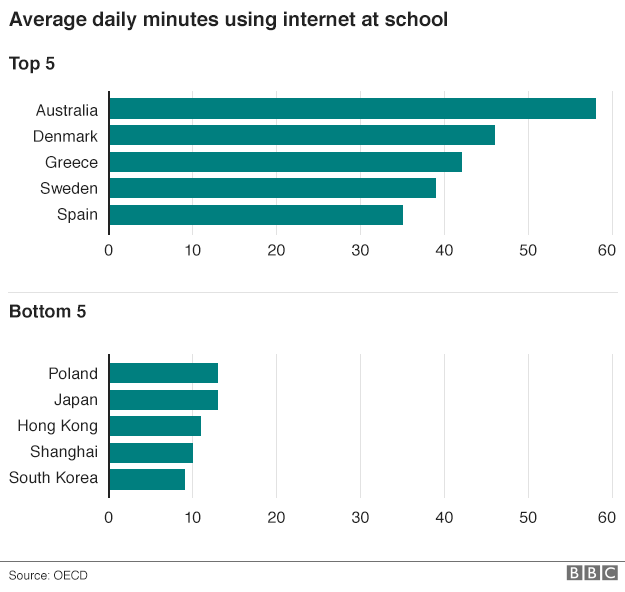

Among the seven countries with the highest level of internet use in school, it found three experienced "significant declines" in reading performance - Australia, New Zealand and Sweden - and three more had results that had "stagnated" - Spain, Norway and Denmark.

The countries and cities with the lowest use of the internet in school - South Korea, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Japan - are among the top performers in international tests.

The study did not gather a figure for the UK's internet time in class, but the UK has among the highest levels of computers per pupil.

But Mr Schleicher says the findings of the report should not be used as an "excuse" not to use technology, but as a spur to finding a more effective approach.

He gave the example of digital textbooks which can be updated as an example of how online technology could be better than traditional methods.

Mark Chambers, chief executive of Naace, the body supporting the use of computers in schools, said it was unrealistic to think schools should reduce their use of technology.

"It is endemic in society now, at home young people will be using technology, there's no way that we should take technology out of schools, schools should be leading not following."

Head teacher John Morris: "When people say too much money is being spent on technology in school, my response is: 'Nonsense'"

Computers in UK schools

1.3m desktop computers

840,000 laptops

730,000 tablets (expected to rise to 939,000 next year)

22% are "ineffective"

Source: BESA

Microsoft spokesman Hugh Milward said: "The internet gives any student access to the sum of human knowledge, 3D printing brings advanced manufacturing capabilities to your desktop, and the next FTSE 100 business might just as well be built in a bedroom in Coventry as in the City."

Head teacher John Morris also strongly rejected the idea.

"We're preparing our children for jobs that don't yet exist," said Mr Morris, head of Ardleigh Green junior school in the London Borough of Havering.

"We're training them to use technology which hasn't yet been invented. So how can you possibly divorce technology from industry or from teaching and learning?

"When people say too much money is being spent on technology in school, my response is 'Nonsense'. What we need is more money, more investment."

The government's behaviour expert Tom Bennett said there might have been unrealistic expectations, but the "adoption of technology in the classroom can't be turned back".

England's schools minister Nick Gibb said: "We want all schools to consider the needs of their pupils to determine how technology can complement the foundations of good teaching and a rigorous curriculum, so that every pupil is able to achieve their potential."