The US's interest rate rise dilemma

- Published

What would a Fed rate rise mean?

Is the Federal Reserve going to raise US interest rates? That's easy. The answer is yes.

Guessing the timing, though, is much more difficult. But there is a possibility that it will happen at the next meeting of the Fed's main policy-making committee, which wraps up on Thursday.

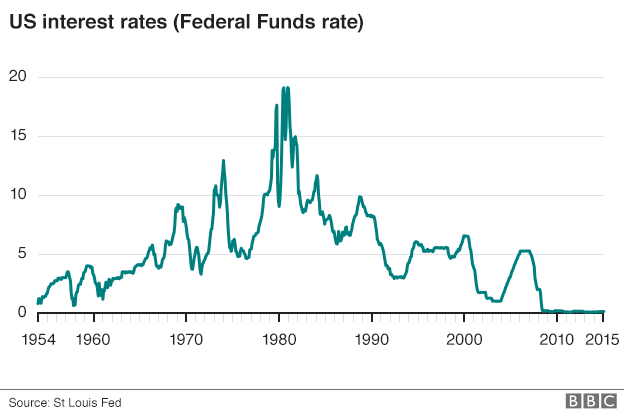

The Fed's main interest rate has been practically zero since the dark days of the financial crisis. It has been unchanged since December 2008, a few weeks after the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers.

I say "practically" because the Fed has a target range, of zero to 0.25%, for an overnight interest rate that banks charge for lending to each other.

It is an unprecedented situation and one the Fed's policymakers want to bring to an end, just as soon as they are satisfied that the country's economy is strong enough.

Jobs market

So, is the economy sufficiently robust to begin the return to normality?

The recovery from the recession that followed the financial crisis began in June 2009., external

Since then the economy has grown at an average annual rate of 2.2%. That's not particularly strong but enough to leave the economy 9% larger than its pre-recession peak.

On the face of it, the jobs market looks pretty healthy. Unemployment is a rather low 5.1%. By contrast the eurozone is struggling with a figure of more than double that.

Federal Reserve chairwoman Janet Yellen put the financial markets on notice months ago that an interest rate rise could come soon.

The latest figures on average earnings showed a stronger-than-expected rise.

A strong employment labour market would suggest a case for raising rates. If firms have to start paying higher wages to get the workers they need, that could mean more inflation.

However, some aspects of the labour market are more troubling. A wider measure of under-employment, which includes people working part-time who would rather be full-time and those who have given up looking for jobs, is still relatively high at 10.3%.

There are also quite a large number of people, more than two million, who are long-term unemployed - that is, without work for more than six months.

Then there is inflation. The Fed's preferred measure (known as personal consumption expenditure inflation) was at 0.3% in July, or, if you exclude volatile food and energy costs, was 1.2%.

The Fed's interpretation of its mandate, external to promote stable prices is an inflation target of 2%.

So, consumer prices do not suggest a strong need to raise interest rates quickly.

Another factor that will weigh against an early increase in rates is the recent volatility in global financial markets linked to China's economic slowdown. It is possible that a very abrupt slowdown could have an adverse impact on the US economy.

'Troubles ahead'

But there are plenty of Fed watchers who think that it should have abandoned its zero interest rate policy years ago - or perhaps never had it in the first place.

Professor John Taylor of Stanford University and a former senior Treasury official under President George W Bush suggests the Fed should have started raising rates, external as along ago as 2010.

He argues that is the implication of a guideline for interest rates known as the Taylor rule, named after him. The rule uses a formula which includes inflation and economic activity to give guidance on what the central banks interest rates should be.

There are other critics of the Fed's ultra-low interest rate policies. Bill Gross, a leading bond investor now at Janus Capital, external, argued that the zero interest rate policy "destroys historical business models essential to capitalism such as pension funds, insurance companies, and the willingness to save money itself."

He added: "If savings wither then so too does its Siamese Twin - investment - and with it, long term productivity - the decline of which we have seen not just in the US but worldwide."

David Stockman, a former senior official under President Reagan thinks the policy has stoked up a bubble in the financial markets. He accused central banks,, external including the US Fed of "massively and insouciantly pursuing financial instability". He warned of "monumental troubles just ahead".

The zero interest rate policy has also been blamed for causing instability in emerging economies' financial markets and so has quantitative easing or QE.

QE is a policy the Fed began when it felt its own interest rate target could go no lower. It is a substitute for lower rates when a central bank wants to provide more stimulus to encourage spending and higher inflation (when they think inflation really is too low).

Investors across the world have tried to anticipate when the Fed might begin "normalising" its interest rate policy

Low rates and QE encouraged money to flow into emerging markets as investors sought better returns, driving up asset prices and currencies.

The end of QE and now the prospect of an interest rate rise soon have encouraged money to leave those same markets and head back to the US where returns on interest bearing assets are likely to improve when the Fed does finally raise rates.

Karishma Vaswani, BBC News

The current global hand-wringing and head-holding over whether the US Fed will or won't raise interest rates later has got investors here in Asia worried about what this means for their economies.

The Fed has become the favourite whipping boy of Asia's central bankers, with cries from India to Indonesia to "just get on with it".

'Good news'

Emerging market governments were concerned by the possibility of destabilising investment flows - first going in and now leaving their financial systems.

Kaushik Basu, chief economist of the World Bank, told the Financial Times, external that a rate rise now could "trigger panic and turmoil" in emerging financial markets. The Bank's economists said in a report this week, external that there is a danger of a perfect storm triggering large capital outflows, which could in turn hit economic growth and financial stability, though they think it's rather more likely that most countries will cope with higher US interest rates.

Some experts appear fairly relaxed about the prospective rate rise. Agustin Carstens, governor of Mexico's central bank, said last month that it would be a sign that the US economy is recovering. "For us that is very good news," he said.

So, what clues have there been from Fed policy makers themselves about when they will move?

William Dudley, President of the Fed's New York operation, said in the wake of the recent financial market instability the case for an early rise "seems less compelling", although he did not close the door on possibility.

But the Fed's Vice-Chairman, Stanley Fischer, made more upbeat comments about the US economy and inflation, suggesting a higher chance of a rate rise soon.

So, will 17 September mark the end of this extraordinary period in American economic policy? My bet: probably not. But it would be only a very small stake that I'd be prepared to risk.