Where next for global interest rates?

- Published

- comments

Next week the US Federal Reserve's Open Markets Committee will meet and decide whether or not tor raise interest rates. It's a tricky choice and that will have global consequences and today the World Bank became the latest organisation to call upon to the delay, external. The World Bank it seems, like the IMF, fears the impact on emerging economies of a rise in US borrowing costs.

While the odds of a hike next week (at least judging by market expectations) have diminished, a rate rise is seen as highly likely in the coming six months. That will be a big moment for the global economy and a moment that can only really be understood by stepping back and looking at the bigger, longer term picture.

For all the attention on short-term rates (as set by the Fed) what really matters is longer term borrowing costs and, across the developed world, they are at (or very near) historical lows. And while these rates are affected by short-term central bank policies, they aren't entirely controlled by them.

The bigger question isn't "will the Fed go in September, December or the early 2016?" but "will long-term borrowing costs remain so low?"

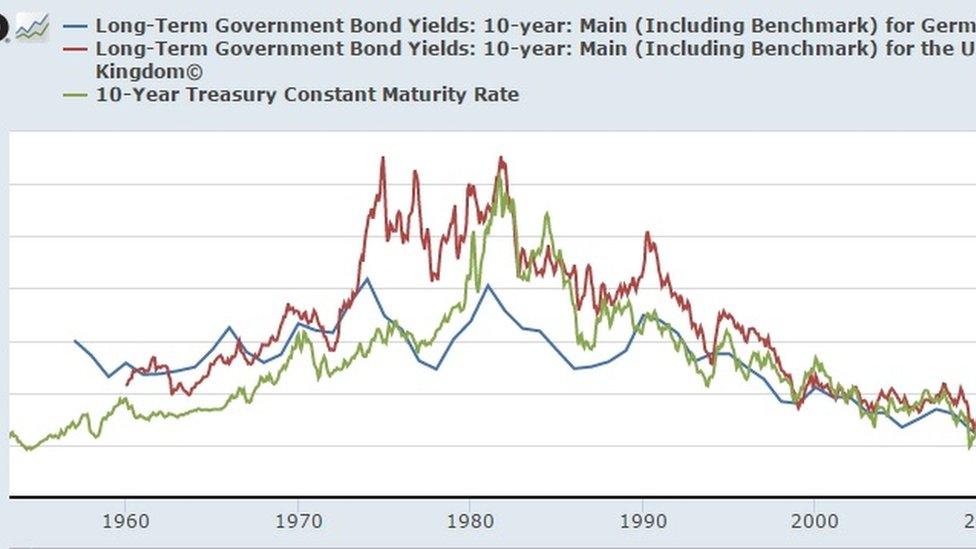

The background is a 35-year bull market for government bonds across the West which has seen their value rise to record highs and the yield (or interest rate on them) fall to record lows. The yield on a bond moves inversely to the price - high bond prices mean low borrowing costs and vice versa.

Long-term borrowing costs have been falling since 1980

To work out if low longer-term interest rates are here to say, one has to work out why they are so low. And that's a matter of real debate among macroeconomists. The five theories below all explain the current level of rates but offer a different prognosis of where they'll head next.

Five Theories

Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers believes the developed economies are afflicted by what he calls "secular stagnation", external. A chronic excess level of desired (economy-wide) saving over investment has depressed interest rates.

Summers's believes that the real (after inflation is accounted for) rate of interest required to generate full employment is now negative and at a time when inflation is low, central banks can't cut short term interest rates enough to generate the real rates required.

This is the issue of the so-called "zero lower bound", the idea that because interest rates (in normal times) can't be cut below zero then there comes a point at which they become ineffective - the economy requires lower rates but central banks can't cut them anymore.

The "zero bound" problem

What really matters is the "real interest rate" - the interest rate minus inflation.

If interest rates are 5% and inflation is 5% the real rate is 0%. But if inflation is 2%, the real rate is 3%.

If inflation is 2% and a real rate of -2% is required to generate enough investment to achieve full employment then that can be achieved by setting interest rates at 0% (rates at 0% minus 2% inflation giving a real rate of -2%).

But if inflation is 0% then getting a real rate of -2% would mean cutting short term interests to -2%.

And central bankers are worried that negative nominal interest rates would cause serious problems for the wider banking system.

For Summers, secular stagnation is a long-running trend and long-term interest rates rare likely to remain low.

For former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke the issue is a global savings glut, external. Countries like China and Middle Eastern oil producers in the 1990s and 2000s and Germany today have got "excess" savings,

These savings have been following to the US (and other advanced economies like the UK) holding interest rates down and strengthening currencies like the dollar. For Bernanke low long-term rates in the West are at least partially driven by an imbalance in the structure of the world economy. If that imbalance faded, interest rates would rise.

Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman's theory combines elements of Bernanke and Summers's own theories, external. He worries that poor demographics, soggy economic domestic demand and very low inflation in the Eurozone have led to a form of "secular stagnation" there.

But Europe's policy response, an attempt to grow by through exports, in effect exports that economic malaise to other countries. A weak Euro boosts European exports but lowers inflation elsewhere and sucks up economic demand that might otherwise be met by domestic production in the US or UK. China's slowdown just adds to these concerns and for Krugman low rates are likely to persistent.

Paul Krugman

Former IMF Chief Economist Ken Rogoff has a more straightforward explanation for low long-term rates: an overhang of debt from what he calls a debt supercycle, external. After binging on debt in the 1990s and 2000s, advanced economies are now feeling the after-effects.

Until such a time as debt levels (both public and private) relative to income have been reduced (a process known as deleveraging), then growth rates - and interest rates - will remain lower than was historically the case.

Of course, for Rogoff there will be an end point, rates will rise as the debt burden is reduced.

Finally, it's worth considering the competing theory of asset manager Toby Nangle.

For him the falling interest rates of the last 30 years were driven by the impact of globalisation.

The world supply of labour available to Western firms soared as China's economy opened up, driving down Western wages and inflation and encouraging firms to use more workers and less capital.

That relative fall in demand for capital helped push down rates. Nangle, though, warns that based on Chinese demographics, this trend may be nearing its end. The world's glut of workers may soon be over.

Where next?

Stepping back from the theorising, three factors have underpinned record low longer term rates.

A belief that short-term interest rates will remain low (longer term borrowing costs being partly a function of short-term borrowing costs), a belief that inflation will remain low (which suggests lower nominal interest rates) and a collapse in what is known as the "term premium" (the extra yield investors demand for having their money locked up for longer).

If anyone of these factors starts to change, longer term rates could start to rise.

For all the fretting about the timing of a US rate rise, it's the bigger picture of longer term borrowing costs that will have an impact on the global economy.

Throughout my entire life time long-term interest rates have basically been falling.

If that trend stops, it would have a much more profound impact than a 0.25% rise in short-term US borrowing costs.

- Published4 September 2015

- Published27 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015